Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (42 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

If 1920 had been a year of Monet celebrations, the following year—with Clemenceau’s eightieth birthday due to fall on September 28—belonged to the Tiger. After escorting Matsukata to Giverny, Clemen ceau had gone to England to collect an honorary degree from

the University of Oxford, whose public orator declared, amid a “burst of enthusiasm,” that no one else’s name would live longer in history.

34

Then, following a trip to Corsica, he had gone to his house in Saint-Vincent-sur-Jard. Nearby, in his childhood village of Sainte-Hermine, a statue in his honor was due to be unveiled amid much celebration on October 2. “This will be, I think, a pretty good fair with dances and fireworks as in the old days,” he wrote to Monet a fortnight before the event. “We shall eat out of our hats, and sleep in the trees or in ditches. See if you feel like coming. My car will transport you.”

35

Monet passed on these festivities but agreed to come the following week, when things would be more peaceful.

Sainte-Hermine turned out in force to celebrate Clemenceau. The tiny village’s two streets were decorated with banners and its houses painted red, white, and blue. People arrived from all over the countryside by train, automobile, truck, horse cart, and bicycle—so many of them, reported a newspaper, that the crowds were thicker than on the boulevards of Paris.

36

A village band played the “Marseillaise,” then the monument was unveiled: a massive sculpture commemorating one of Clemenceau’s visits to the front, showing him on the parapet of a trench, staring determinedly forward with six soldiers at his feet. For many of those present, the flesh and blood Clemenceau was even more impressive than the effigy carved from stone.

“Victoire de la France!”

he declared in an extemporaneous address.

“Victoire de la civilisation! Victoire d’humanité!”

According to the press reports, the “grand old man” looked younger than ever: “He looks suntanned,” reported

Le Petit Parisien

, “bronzed by the sea breezes and the bright ocean sun.”

37

Life in the Vendée certainly agreed with Clemenceau. A few days earlier he had written to Monet: “As for me, my hands are burning from eczema and my shoulder is knackered, but I forget my woes as soon as the waves tickle the soles of my feet. I would not be surprised if you got on with some painting here. The sky and the sea are a palette of blues and greens.”

38

Clemenceau’s house was only forty yards from the Atlantic, from which it was separated by a stretch of sandy ground on which he was cultivating a garden. To Monet he called his small patch of the Vendée “my fairyland of earth, sky and birds.”

39

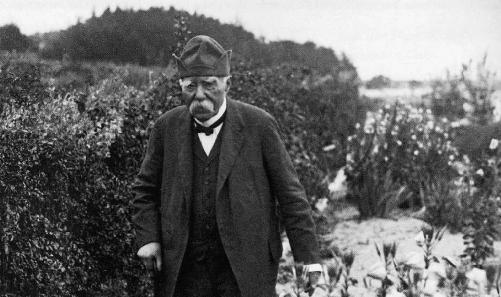

Clemenceau in his garden at Belébat

Clemenceau explained to one visitor that the name of his house, Belébat, was old French for

beaux ébats

, meaning happy entertainment.

40

Happy entertainments were certainly planned for Monet, who, two days after the festivities at Sainte-Hermine, arrived in the chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce. He was accompanied by Blanche and Michel. “I have two small rooms for you and the Blue Angel, where she will be able to spread her wings,” Clemenceau had promised. “Your son will be lodged in a nice house with a car and a makeshift garage next to mine.”

41

Clemenceau was happily domesticated in this corner of the world where he was spending summers and holidays.

42

He was tended by an elderly cook named Clothilde and a manservant, Pierre, who addressed him as “Monsieur le Président.” He had a donkey named Léonie, housed in a stable at one end of the house, and a little dog named Bif, an animal with “the brains of a sardine,” as he apologized to his guests; he frequently chastised the creature for barking by shouting in American-accented English: “Cut it out!” The kitchen where Clothilde prepared the meals had a flagstone floor, whitewashed walls, and exposed beams. Outside the door was a rustic bench on which, after meals, Clemenceau often sat staring at his humble stretch of garden and the mighty ocean beyond. When in residence he raised his standard on a flagpole: a twenty-foot-long windsock in the shape of a carp, given to him a few months earlier by Matsui Keishiro, the Japanese ambassador to France.

Gardening, painting, food: Clemenceau had tempted Monet to the Vendée with all three of these great loves. All three, no doubt, were suitably indulged during the eight-day visit. As with Sacha Guitry and Charlotte Lysès at Les Zoaques eight years earlier, so, too, with Clemenceau at Belébat: Monet offered advice on Clemenceau’s little stretch of dunes, bringing some plants with him, including ones that Clemenceau called

boules d’azur

—blue flowering plants that reminded him, apparently, of Blanche’s eyes.

43

(Clemenceau frequently made reference to Blanche’s blue eyes, and indeed this seemed to be why—in combination with her endless patience with the turbulent curmudgeon who was her stepfather—he called her the Blue Angel.) This blue plant, evidently some sort of thistle, was one of the few things that would survive the winter in Clemenceau’s garden, which was buffeted by the harsh and salty Atlantic gales. Monet would also give Clemenceau roses, aubrietas, daffodils, and gladioli.

44

“Paintings await you,” Clemenceau had promised Monet.

45

Monet did indeed do some painting during his visit—not of the sea (as Clemenceau clearly expected) nor of the modest patch of garden, but rather a watercolor of Belébat itself, as if commemorating for himself his friend’s seaside abode.

46

Thanks to Clothilde, meals had become almost as much of a ritual at Belébat as at Giverny. A visitor who arrived a few days before Monet was treated to sardines and Clothilde’s ragoût of mutton.

47

Monet was presumably served the cabbage soup with which he had been tempted a year earlier, but Clothilde’s specialty was poulet Soubise, a dish named after the prince de Soubise, a seventeenth-century marshal from the Vendée. Roasted, chopped up, and cooked in a thick onion sauce, this chicken dish took forty-eight hours to prepare. Clemenceau once proclaimed: “I like the sauce even better than the marshal did.”

48

One of Clemenceau’s great pleasures was making the ninety-minute-long expedition to Les Sables-d’Olonne to purchase ingredients from the market, including shrimps from a woman named Mathilde, whom he cheerily observed charged him double. Another visitor that October described Clemenceau’s flirtatious banter with the “vast and

radiant Mathilde,” who tried to make him purchase more, “but he replied that he wanted nothing else, except Mathilde herself. She replied that she was too big to be taken away. Clemenceau pointed to the enormous waiting automobile and stated that he liked his women plump.” In the market he also purchased pears, prunes, cake, and newspapers. As soon as he arrived, a cry went up: “

Voilà le Tigre!

” At the patisserie a young woman in a butterfly-shaped headdress thanked him for doing her the honor and offered to carry his purchases to the automobile.

49

Then it was back along the lanes to Belébat, with Clemenceau urging his chauffeur, the faithful Albert, to drive ever faster. (Several years later, with Albert at the wheel, Clemenceau’s motorcar would accidentally run down and kill a woman, a Madame Charrier, while returning from Les Sables-d’Olonne—although Clemenceau insisted that on that occasion the Rolls-Royce had not been speeding.)

50

The carp would be run up the flagpole, fluttering and snapping in the breeze. It is possible to imagine Clemenceau and his guests listening to the sighing of the pines and the rumble of waves crawling across the strand of beach, and watching, as dusk crept over the ocean, the pulses of light from the great lighthouse eighty miles away in the Gironde estuary. “Eight small suns shall fade during your stay,” Clemenceau had written to Monet, “but our friendship never will.”

51

After the eight suns extinguished themselves in the ocean, Monet returned to Giverny. Barely had he disappeared down the lane than Clemenceau, in his study overlooking the ocean, composed a letter to him. “Philosophy teaches us,” he wrote, “that the greatest pleasures are short. Your visit has been particularly vivid since passed in a flash. You especially deserve credit for having undertaken the visit since you’re as lively as a tortoise...As for me, I shall continue to be whirled around like a top whose strings are pulled one by one by all the devils in Paradise.”

52

THE MATTER OF

Monet’s donation to the state must have been one of the topics of conversation during the visit to Belébat. The situation was still unresolved, and so Monet wrote to Clemenceau at the end of October to reiterate his conditions. He would accept the Orangerie as

a venue as long as the administration undertook “to do the work that I judge necessary.” Back in June he had informed Arsène Alexandre that he was willing to donate more than a dozen works, and now he restated the offer: he told Clemenceau that he was willing to offer eighteen works to the state. He enclosed a plan showing how the space in the Orangerie could be separated into two separate rooms, both elliptical. “If the administration accepts this proposal and undertakes to do the necessary work,” he repeated, “the affair will be settled.”

53

Clemenceau, who had returned to Paris on October 22, swung into action. He met with Paul Léon at the beginning of November, then reported happily to Monet: “Everything is arranged according to the conditions you set.”

54

He arranged for Léon and Louis Bonnier to visit Giverny, which they did a week later, with the upshot that, as Monet pointedly reminded Léon one day later, he agreed to donate eighteen canvases making up eight compositions; these panels would be “destined for two rooms arranged as ovals.”

55

All that was needed now was a new architectural plan from Bonnier as well as a notarized contract making the donation official and legally binding on both parties.

Negotiations had therefore reached more or less the same point they were at exactly a year earlier: the paintings and a venue had been determined, and now Bonnier was at work on a design. Predictably, exactly the same difficulties presented themselves. Within weeks Monet was complaining to Clemenceau that Bonnier’s plan for the Orangerie was unsuitable and that, as before, the architect was trying to cut costs.

56

Once more an intervention from Clemenceau was required. In the middle of December, after a meeting with Paul Léon, he was able to reassure Monet: “He will do everything you want...There will be no difficulties.”

57

The result of these negotiations was that Bonnier was removed from the project and another architect, forty-five-year-old Camille Lefèvre, architect in chief of the Louvre and the Tuileries, appointed in his place. The only problem was that no one seemed to have informed Bonnier of this change, and so Monet was taken aback when his latest set of plans arrived. “I don’t know how to respond to him,” Monet complained to Léon.

58

Bonnier may well have been relieved to be rid of the project. Within weeks Lefèvre, too, found himself mired in design difficulties, in particular with how to provide adequate natural light despite the fact that for structural reasons the roof beams in the Orangerie could not be altered or moved. Yet again Monet complained to Clemenceau, who by this point was becoming thoroughly fed up with the constant wrangling between the artist and his long-suffering architects. In early January he wrote a blunt and impatient letter to Monet, declaring: “It must be settled.”

59

Lefèvre produced three different plans over the next few months, all of them providing ovoid rooms, while Clemenceau worked on the wording of the terms of the agreement, which went back and forth between him and Léon. Meanwhile, Monet sent anxious telegrams to Clemenceau, who was beginning to find him, as he readily confessed, “a pain in the backside.”

60

Monet’s mood darkened. In a rare moment of self-scrutiny, observing the difficulties his tempers were causing Blanche, he admitted to Clemenceau: “What a bastard I am.”

61

Léon and the architects may have agreed with this assessment. However, by the spring of 1922 matters were finally shunting along toward their conclusion. In March, Monet informed Léon that he was expanding his donation to twenty-two panels making up twelve compositions, though he noted that the compositions “may be modified during installation.”

62

In other words, the number of paintings depended on the actual space they would inhabit, with room for flexibility. The documents were prepared and ready to sign by early April, although Monet still found it necessary to complain about the “sluggishness” of Léon and his legal representative in making their way to Giverny.

63

At long last, on April 22, in the offices in Vernon of Maître Baudrez, Monet’s lawyer, the artist and Léon put their signatures to the deed of donation. Monet undertook to deliver nineteen (rather than twenty-two) panels to a “Claude Monet Museum” within two years—that is, by April of 1924.