Making Ideas Happen (8 page)

Read Making Ideas Happen Online

Authors: Scott Belsky

Keep an Eye on Your Energy Line

I spent one afternoon a while back with Max Schorr, the publisher of

GOOD

, a monthly magazine focused on doing good, and his team. A group of true idealists, the staff found themselves constantly overburdened and overextended—striving to do everything while also striving for perfection. As Schorr put it, “At

GOOD

we hate to waste anything, and given our surplus of idea generation, the one thing we waste tons of is energy.”

If you have lots of ideas, you probably have the tendency to get involved with or start lots of projects. Projects can require tremendous amounts of mental energy, from capturing and organizing the elements to actual y applying your creative talents to solve problems and complete Action Steps. Energy is your most precious commodity.

Regardless of who you are, you have only a finite amount of it. Just as a computer’s operating capacity is limited to the amount of memory (or RAM) instal ed, we al have our limits.

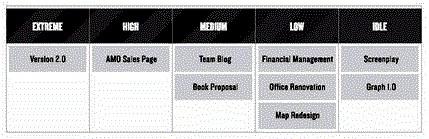

As you decide where to focus your precious energy, visualize al of your projects along a spectrum that starts at “Extreme” and goes al the way down to “Idle.” How much energy should your current projects receive?

Place your projects along an energy line according to how much energy they

should receive.

At any given point in time there may be a couple of projects that you should be extremely focused on, while others may be semi-important or perhaps idle for the time being. If you were to place projects along the spectrum, the extremely important projects would be placed on the “Extreme” end of the spectrum and the others would be placed accordingly farther down toward “Idle.” Keep in mind that you are

not

placing your projects along the spectrum based on how much time you are spending on them. Rather, you are placing your projects according to how much energy they should receive based on their importance.

A project placed at the “Extreme” end of the energy line should be the most important for the time being—worthy of the majority of your energy. Projects should be placed according to their economic and strategic value. The concept of the Energy Line is meant to address our tendency to spend a lot of time on projects that are interesting but perhaps not important enough to warrant such an investment of energy.

Viewing your projects along an Energy Line prompts certain questions: How much of your time are you spending on what? Are you focused on the right things?

Amidst the everyday craziness of a creative enterprise, it is hard to keep track of energy and where it’s being used. The Energy Line is a simple mechanism to help us measure and adjust a team’s energy al ocation. We have seen many people use similar concepts to help themselves visualize the projects in their lives according to priority. After considering your Energy Line for just a few minutes, you can get a sense of whether your energy for that week, day, or even that hour is being managed properly.

The Energy Line exercise is also a helpful way for teams to agree on prioritization.

Some teams wil gather around a corkboard or whiteboard and, together, write the names of al of their major projects on smal cards. The team wil then place the cards along the Energy Line according to their importance and how much col ective focus each project should get from the team. At first, you may find that too many projects are being placed near the “Extreme” zone of the spectrum. This is a natural tendency because each project solicits different levels of interest from different members of the team. Such disagreements are great because they help the team prioritize col ectively.

As you consider your Energy Line, you wil want to make the tough decisions about what projects need to live on low energy for a while. Whether or not you use the Energy Line exercise, al teams should discuss and debate how their energy is al ocated.

Energy is a finite resource that is seldom managed wel .

If every Action Step belongs to a project and you have your projects spread across a spectrum of how you wish to al ocate your energy—then you wil have clear direction on which Action Steps you should do first and how you should budget your time.

Reconciling Urgent vs. Important

While the Energy Line perspective can help us al ocate our energy across projects, we are stil bound to drift off course as soon as unexpected and urgent items arise. When something is urgent, we rush to do it. Even if it can wait—or is someone else’s job—our tendency is to hoard urgent items because they always seem more pressing than stuff associated with longer-term projects. As leaders of creative projects, we feel an impulse to solve everything quickly. I cal this “Creator’s Immediacy”—an instinct to take care of every problem and operational task, no matter how large or smal , as soon as it comes up, similar to a mother’s instinct for the care of a newborn baby. However, it becomes nearly impossible to pursue long-term goals when you are guided solely by the most recent e-mail in your in-box or cal from a client.

Fortunately, there are ways to manage the urgent stuff without compromising progress on long-term projects. The capacity to do so starts with compartmentalization, shared values, and the power of clarity.

If you’ve ever used Priceline.com, an ATM, or a cel phone, then you’ve used technology developed and patented by Walker Digital. Primarily a research and development outfit, this seventy-person company has developed and successful y patented a variety of ideas across technological industries. As an intensely creative company, the Walker Digital team is constantly developing new ideas and is liable to suffer from Creator’s Immediacy. Nevertheless, the company’s leadership takes pride in its ability to operate efficiently on a daily basis while also innovating with the future in mind.

At any given moment, half the company is dreaming up new ideas while the other half is managing and licensing the patented ones. In such an environment, one might expect the urgent operational needs of the business to quickly compromise the energy al ocated to multiyear research projects. But they don’t. Walker Digital’s track record suggests that it has been able to maintain a focus on long-term projects despite the growing operational demands.

President Jon El enthal admits how difficult it is to develop new ideas and operate a business at the same time. “Development and operations are fundamental y different burdens,” El enthal explained to me. “The gravitational pul over an operator is nearly impossible to escape. When faced with a choice of what to do next, what must be done today wil always trump what might be developed for tomorrow.” In other words, there is a great tension between the urgent operational items with current projects that arise every day and the more important (but less timely) items that are liable to be perpetual y postponed. Without some sense of discipline, the company would drown in the everyday “urgent items” to the detriment of the company’s success over time.

Walker Digital’s distinctive culture may help explain its ability to consistently focus on long-term projects. For starters, the company is privately owned. “No normal investor would ever have the patience for turning ideas into patents,” explains El enthal. The time and expense invested in the patent side of the business might scare away ordinary investors, but for the Walker Digital employees, it has only reinforced the value of ideas.

“The amount of energy we invest in turning ideas into commercial assets encourages people to maintain their ideas—and keep them top of mind. . . . Everyone knows how valuable an idea may become for us.”

A shared respect for the potential of ideas empowers people to speak up when day-to-day operations start to interfere. El enthal and his executive team take particular pride in the company’s straightforwardness. His col eague and chief marketing officer, Shirley Bergin, elaborated: “Our value for clarity overcomes the risk and fear of speaking up when something doesn’t make sense.” For a company that is entrenched in both operations and long-term innovation simultaneously, the aspiration for clarity maintains a constant, healthy debate around energy al ocation.

Walker Digital’s shared value for ideas—and a culture that constantly seeks clarity —empowers people to quarantine themselves for extended periods of time while researching long-term projects. The company is even structured to al ow half the company to engage in long-term pursuits while the other half oversees the legal and operational side of managing the patents. Through a finely tuned culture, Walker Digital is able to keep long-term pursuits alive.

Whether you work alone or within a team (or company) ful of people, the first step is to discern what is urgent versus what is important in the long term. Especial y in the creative environment, important projects often require substantive time and mental loyalty. The constant flow of “urgent” matters that arise for you—the daily questions from clients, the bil s to pay, the problems and glitches—threaten to interfere with your long-term objectives. The chal enge is compounded for projects that you created yourself. As the creator, you feel a sense of ownership and, with it, a heavy impulse to address every task or problem immediately.

There is too much focus on “fixing.” How can you maintain long-term objectives rather than suffer at the mercy of urgent tasks? It is cal ed prioritization. And to prioritize, you must become more disciplined and use methods that prompt compartmentalization and focus.

Here are some tips to consider:

Keep two lists.

When it comes to organizing your Action Steps of the day—and how your energy wil be al ocated—create two lists: one for urgent items and another for important ones. Long-term goals and priorities deserve a list of their own and should not compete against the urgent items that can easily consume your day. Once you have two lists, you can preserve different periods of time to focus on each.

Choose five projects that matter most.

Recognize that compromise is a necessity.

Some people narrow their list of important items to just five specific things. Family is often one of the five, along with a few other specific projects or passions that require everyday attention. The most important aspect of this list is what’s

not

on it. When urgent matters come up, the “important” stuff you are working on that didn’t make your list should be dropped. You may be surprised to see how much energy you spend on off-list items!

Make a daily “focus area.

” About ten months after launching our online productivity application, Action Method Online, a user suggested to me that our team create a special “focus area” within the application to which you could drag up to five Action Steps—from any project—that you wanted to focus on today. This arrangement suggested that, regardless of whatever else cropped up that day, the focus area had to be cleared before you went to sleep at night. Keeping your focus list short makes it easier to constantly review throughout the day—to ensure that you focus on the more important items.

Don’t dwell.

When urgent matters arise, they tend to evoke anxiety. We dwel on the potential negative outcomes of al the chal enges before us—even after action is taken.

Worrying wastes time and distracts us from returning to the important stuff. When it comes to addressing urgent items, break them down into Action Steps and chal enge yourself to real ocate your energy as soon as the Action Steps are completed.

It is also helpful to consider whether or not certain concerns are within or beyond our influence. Often our worries are for the unknown and there is nothing more we can do to influence the outcome. Once you have taken action to resolve a problem, recognize that the outcome is no longer under your influence.

Don’t hoard urgent items.

Even when you delegate operational responsibilities to someone else, you may stil find yourself hoarding urgent items as they arise. When you care so deeply about a project, you’l want to resolve things yourself. Say an e-mail arrives from a client with a routine problem. Even though the responsibility may lie with someone else on your team, you might think, “Oh, this is real y a quick fix; I’l just take care of it.” And gradual y your energy wil start to shift away from long-term pursuits.

Hoarding urgent items is one of the most damaging tendencies I’ve noticed in creative professionals who have encountered early success. When you are in the position to do so, chal enge yourself to delegate urgent items.