Making Ideas Happen (9 page)

Read Making Ideas Happen Online

Authors: Scott Belsky

Create a Responsibility Grid.

If you have a partner, you’l want to divide and conquer various tasks for efficiency. Some teams create a “Responsibility Grid” to help them compartmentalize. This is also a tool that I used with co-heads of teams while working at Goldman Sachs. Across the top of the chart (the horizontal x-axis) you write the names of the people on the team. Then, down the left side of the page (the vertical y-axis), you write al of the common issues that come up in a typical week. Place a check in the grid for which team member (listed along the top) is responsible for which type of issue (along the side).

For example, if you’re a smal application-development team, your list of issues might include “inquiry for a sale or team discount,” “bug report from a user,” “report of lost data,” and “suggestion for a new feature.” As a team, you go through each person’s column and check the issues he or she is responsible for. Once completed and agreed upon, this chart sends an important message about who is (and, more important, who is not) al owed to respond to certain issues. The exercise in itself wil help quench everyone’s impulse to do everything themselves and wil streamline your team’s operations.

Use a Responsibility Grid to decide who does or does not need to get involved

with whatever comes up.

Create windows of nonstimulation.

To achieve long-term goals in the age of always-on technology and free-flowing communication, create windows of time dedicated to uninterrupted project focus. Merlin Mann, founder of the productivity Web site 43folders.com, has cal ed for the need to “make time to make.” It is no surprise that Mann is also known for begging people

not

to e-mail him (in fact, he refuses to answer any suggestions or requests via e-mail). After years of writing about productivity and life hacks, Mann realized that the level of interruption increases in direct proportion to one’s level of availability.

Many people I have interviewed preserve blocks of time during their day—often late nights and early mornings—as precious opportunities to make progress on important items with little risk of urgent matters popping up. For Mac users, there is a standard desktop feature cal ed “Spaces” that al ows you to change your desktop view to show only certain applications at a time. One standard practice I have seen in the field is keeping e-mail and al other communication applications in a single Space—and then, when writing or working on a project, keeping that application in a different Space. If you don’t use Apple’s Spaces feature, you can simply minimize (or quit) al communication applications during certain periods of your day.

Of course, this practice requires great discipline and the ability to extract yourself from reactionary work flow—the state of always responding to what comes in to us. However, through windows of nonstimulation, you wil reclaim the power to focus on what you believe is most important.

Darwinian Prioritization

Of course, we are not always equipped to manage our energy and determine urgent versus important on our own. Despite our attempts to compartmentalize, emotion and anxiety are likely to interfere with our judgment as we seek to prioritize actions and decisions. Those around us—our col eagues, clients, friends, and family—can add a positive natural force for prioritization if we are wil ing to channel it. I cal this “Darwinian Prioritization” because it works through natural selection: the more we hear about things, the more likely we are to focus on them. Another less glamorous term for this process is “nagging.”

Many teams rely on the natural force of nagging and peer pressure to better prioritize and al ocate energy across projects. One such company is a New York-based creative agency cal ed Brooklyn Brothers. The agency’s senior partners, Guy Barnett and Stephen Rutterford, manage a smal but particularly prolific team that churns out work for clients as wel as in-house entrepreneurial ventures that range from chocolate bars to children’s books.

“We have lots of ideas . . . we are a factory of ideas . . . but we develop less than 10

percent of them,” Rutterford explained to me. After asking a battery of questions about their project management tools and creative process, I was surprised to learn that they were very hands-off with their team. Rather than use advanced project management systems, the team cal s meetings only when needed (rather than having regularly scheduled checkins). At one point during our discussion, Barnett leaned forward and explained, “Our secret in execution around here is real y quite simple: nagging.” He went on: “We repeat stuff like robots a thousand times. . . . A best practice for us is to use nagging tempered by humor; we sit around a table and feel responsible to each other. . .

. If you’re annoying, people wil do things because they’l want you to shut up!” At Brooklyn Brothers, the open office-seating structure makes it even easier for people to stand up and quickly remind (nag) one another about an impending deadline or upcoming meeting. This may sound like a chaotic way for a team to prioritize and manage its energy, but a surprising number of highly productive teams swear by it.

I’ve noticed that nagging as a positive force for prioritization works across other industries as wel . Roger Berkowitz, CEO of Legal Sea Foods—a $215-mil ion company with over four thousand employees—explained in an interview with

Inc.

magazine how his work style depends on the forces of nagging. “People who want me to do something . . . have to remind me repeatedly,” he explained. “It’s management by being nagged.”

The reliance on—and even the encouragement of—nagging may at first appear bothersome. It may be annoying to be constantly reminded about something while trying to immerse yourself in a creative project. However, amidst the chaos of meetings and trying to prioritize the elements of multiple projects, nagging from others helps you prioritize by natural selection. When someone is consistently bothering you about something, chances are you have become a bottleneck in the team’s productivity. As you al ocate your energy across projects, it is often difficult to know how your decisions affect others. Certain Action Steps on your list may become more important than others due to popular demand. Nagging is a force that can boost productivity through col ective prioritization—as long as the culture supports it.

EXECUTION:

Always Moving the Ball Forward

Genius is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration.

—Thomas Edison

THOMAS EDISON’S FAMOUS

quote rings especial y true in the world of innovation.

Execution, of course, is predominantly perspiration. Organizing each project’s elements, scheduling time, al ocating energy, and then relentlessly completing Action Steps comprises the lion’s share of pushing ideas to fruition.

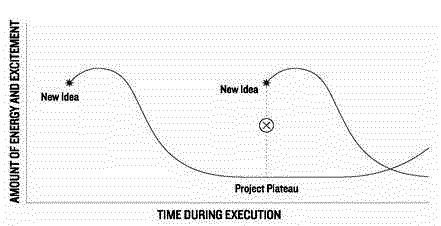

Yet, as we move further along the trajectory of execution, we are liable to get lost in the “project plateau.” We know we’re on the plateau when we are overwhelmed with Action Steps and can see no end in sight. Our energy and commitment—and thus a wil ingness to tolerate the sometimes painful process of execution—are natural y high only when an idea is first conceived. The honeymoon period quickly fades as Action Steps pile up and compete with our other ongoing commitments. Our ideas become less interesting as we realize the implied responsibilities and sheer amount of work required to execute them.

The easiest and most seductive escape from the project plateau is the most dangerous one: a new idea. New ideas offer a quick return to the high energy and commitment zone, but they also cause us to lose focus. As the new star rises, our execution efforts for the original idea start to fal off. The end result? A plateau fil ed with the skeletons of abandoned ideas. Although it is part of the creative’s essence to constantly generate new ideas, our addiction to new ideas is also what often cuts our journeys short.

Avoid the tendency to escape the lulls of the project plateau by developing new

ideas.

To push your ideas to fruition, you must develop the capacity to endure, and even thrive, as you traverse the project plateau. You must reconsider the way you approach execution. The forces you can use to sustain your focus and renew your energy do not come natural y. Making ideas actual y happen boils down to self-discipline and the ways in which you take action.

By proposing the Action Method as the most effective way to approach projects, I’ve already made the argument that you should navigate life with a bias toward action. But why do we so often struggle to actual y take action?

There are many reasons for procrastination. Aside from the desire to generate more ideas rather than take action on existing ones, another factor that discourages action is fear. We have a fear of rejection or premature judgment. Many novelists and other artists admit that they are sitting on half-baked projects that have not been shared with anyone because they’re “just not ready yet.” But what if one never real y feels ready?

Sometimes, to delay action even longer, we resort to bureaucracy. Bureaucracy was born out of the human desire for complete assurance before taking action. When we don’t want to take action, we find reasons to wait. We use “waiting” nicknames like “awaiting approval,” “fol owing procedures,” “further research,” or “consensus building.”

However, even when the next step is unclear, the best way to figure it out is to take some incremental action. Constant motion is the key to execution.

Act Without Conviction

The truth is, creativity isn’t about wild talent as much as it’s about productivity. To find a few ideas that work, you need to try a lot that don’t. It’s a pure numbers game.

—Robert Sutton, professor of management science and engineering, Stanford

School of Engineering

The notion of taking rapid action without conviction defies the conventional wisdom to think before you act. But for the creative mind, the cost of waiting for conviction can be too great to bear. Waiting builds apathy and increases the likelihood that another idea wil capture our fancy and energy. What’s more, if you were to build lots of conviction after much analysis, it might leave you too deeply committed to a single plan of action and unable to change course when necessary.

Traditional practices such as writing a business plan—ultimately a static document that wil inevitably be changed on the fly as unforeseen opportunities arise—must be weighed against the benefits of just starting to take incremental action on your idea, even if such early actions feel reckless. Taking action helps expose whether we are on the right or wrong path more quickly and more definitively than pure contemplation ever could.

During one of my visits to IDEO, a world-renowned product innovation and design consultancy, I had the opportunity to spend a morning with Sam Truslow, a senior team member who oversees the company’s work with organizations like Hewlett-Packard.

Like many folks at IDEO, Truslow readily admits that the famed “idea factory” is widely misunderstood. “What makes us tick is not just having good ideas, despite what clients think,” says Truslow. “When people want new ideas, what they are real y saying is that they can’t execute.” What IDEO does provide is an incredibly effective structure for the execution of ideas—often ideas that their clients may have already had. For Truslow, IDEO’s tendency to constantly “make stuff ” throughout the creative process is perhaps the most critical ingredient to the company’s success.

In the process of idea generation in most environments, promising leads become diluted through debate or are simply skipped over during the natural progression of discussion. When a group decides to act upon an idea—whether this idea requires initial research or some sort of preliminary design or mock-up—the team wil often strive for consensus before even discussing execution. This search for consensus stal s real progress.

IDEO’s common practices for idea implementation more closely resemble a curious four-year-old experimenting with LEGOs than a wel -established corporate design and business development firm. When team members have an idea for how something might look or function, they’l simply have a prototype built and start tinkering— despite what stage of the design process they are in. IDEO’s rapid prototyping practices are part of a clever strategy to overcome some of the biggest boundaries to making ideas happen.

Team members at IDEO rapidly pursue ideas even during the preliminary phases of a project. They are able to do so using a unique set of resources that empower employees to take rapid action on the fledgling ideas that arise during brainstorming. For starters, al designers have access to “The Shop”—a multimil ion-dol ar ful y staffed department within the company that has the latest tools to rapidly create mock-ups out of metal, wood, or plastic. A quick tour of The Shop provides a tangible, visual history of the development of landmark projects like the standard mouse for Microsoft with a scrol wheel and the Palm V design for 3Com.