Male Sex Work and Society (43 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

| Mental Health Aspects of Male Sex Work | |

JULINE A. KOKEN DAVID S. BIMBI |

“

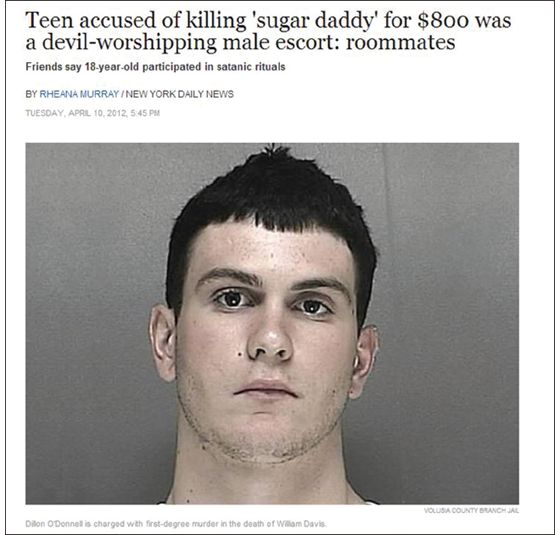

DEVIL WORSHIPPING MALE ESCORT ACCUSED OF KILLING SUGAR DADDY

,” screamed a recent headline in the

New York Daily News

(Murphy, 2012). The piece described a gruesome murder allegedly committed by an 18-year-old male escort who reportedly participated in “satanic rituals.” The victim, a 36-year-old man who had apparently hired the escort after communicating with him on “gay websites,” was found bludgeoned and stabbed to death (see

figure 9.1

). The media coverage of the case painted a lurid picture of a mentally unstable young man who had recently begun working as an escort while employed at a low-paying retail chain by day. His victim and presumed client was an older man, a “sugar daddy” (at the age of 36) who reportedly owed the young man a substantial amount of money. The coverage reinforced and perpetuated the stereotype of the male sex worker as young, poor, mentally deranged, and criminal. The client was also portrayed stereotypically, as an older man who was victimized by the young sex worker.

DEVIL WORSHIPPING MALE ESCORT ACCUSED OF KILLING SUGAR DADDY

,” screamed a recent headline in the

New York Daily News

(Murphy, 2012). The piece described a gruesome murder allegedly committed by an 18-year-old male escort who reportedly participated in “satanic rituals.” The victim, a 36-year-old man who had apparently hired the escort after communicating with him on “gay websites,” was found bludgeoned and stabbed to death (see

figure 9.1

). The media coverage of the case painted a lurid picture of a mentally unstable young man who had recently begun working as an escort while employed at a low-paying retail chain by day. His victim and presumed client was an older man, a “sugar daddy” (at the age of 36) who reportedly owed the young man a substantial amount of money. The coverage reinforced and perpetuated the stereotype of the male sex worker as young, poor, mentally deranged, and criminal. The client was also portrayed stereotypically, as an older man who was victimized by the young sex worker.

Background

The image of the male sex worker (MSW) or “hustler” has long been associated with illness, danger, and deviance, in many ways mirroring the stigma of homosexuality (Bimbi, 2007; Scott, 2003). Historically, research has framed men’s participation in the sex trade as a symptom of pathology, delinquency, or antisocial behavior (Bimbi, 2007; Scott, 2003; Simon et al., 1992). Young MSWs also have been portrayed by some scholars as masculine heterosexuals who were seduced and indoctrinated into homosexuality by “perverted” older homosexuals (Scott, 2003), while others framed young male hustlers as a threat to their clients and to society (Kaye, 2003). This cultural narrative continues to be reflected in current portrayals of male prostitution in the media, such as the “Satan-worshipping escort” who allegedly murdered his “sugar daddy” client.

The gradual normalization of homosexual identity in research and popular culture has led to a shift away from explanations of men’s involvement in prostitution as a symptom or cause of pathology toward portrayals of MSWs as rational actors engaging in paid labor (Bimbi, 2007; Browne & Minichiello, 1995; Koken et al., 2004). The reframing of prostitution as sex work has been accompanied by an increased focus on public health, particularly the risk of transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (described further in David Bimbi’s chapter in this volume on MSWs and public health). However, while the framing of male prostitution has shifted from pathology to public health concerns (Ross et al., 2012; WHO, 2012), there has been little accompanying attention paid to the mental health of MSWs.

FIGURE 9.1

“Satan Worshipping Male Escort,”

New York Daily News

headline for story by Rheana Murray.

Source:

Mugshot courtesy of Volusia County Jail, Florida

New York Daily News

headline for story by Rheana Murray.

Source:

Mugshot courtesy of Volusia County Jail, Florida

The Social Meanings of Male Sex Work

Research on the mental health of sex workers has largely focused on the needs of women. This may reflect a larger social bias toward framing women as “vulnerable/victims,” while men are seen as rational, agentic, and entrepreneurial, and therefore less vulnerable to emotional problems (Dennis, 2008; Marques, 2011).

1

Thus the literature on sex workers in many ways reflects larger paradigms of masculinity (rational, capable) and femininity (vulnerable, hysterical; Browne & Minichiello, 1996). Investigation into the mental health of MSWs in recent years spans two broad domains: (1) the personal impact of participating in sex work—a highly stigmatized activity—and how men manage and resist stigma; (2) the prevalence and correlates of mental health problems, physical health problems, sexual risk behaviors, and experiences or a history of victimization.

1

Thus the literature on sex workers in many ways reflects larger paradigms of masculinity (rational, capable) and femininity (vulnerable, hysterical; Browne & Minichiello, 1996). Investigation into the mental health of MSWs in recent years spans two broad domains: (1) the personal impact of participating in sex work—a highly stigmatized activity—and how men manage and resist stigma; (2) the prevalence and correlates of mental health problems, physical health problems, sexual risk behaviors, and experiences or a history of victimization.

While the stigma of homosexuality has waned in the West in recent years (Minton, 2001), men’s participation in “prostitution” remains a stigmatized activity (Browne & Minichiello, 1996; Koken et al., 2004; Morrison & Whitehead, 2005), as the media coverage of the Satan-worshipping male escort shows. MSWs are doubly marginalized, due to their participation in prostitution as well as engaging in sex with other men (Koken et al., 2004). These men must manage their own feelings and self-perceptions relative to being a sex worker serving male clients, as well as the potential judgments of their loved ones. Thus researchers have explored men’s motivations for entering the highly stigmatized sex trade (Mimiaga et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2013; Uy et al., 2004) and their identity-management strategies for coping with or resisting the stigma associated with being an MSW (Browne & Minichiello, 1996; Koken et al., 2004; Mclean, 2012; Morrison & Whitehead, 2005).

Coping with Sex Work Stigma

Several studies have examined cognitive strategies for resisting or managing the stigma associated with being a prostitute. Many MSWs report highlighting the agentic and entrepreneurial aspects of their participation in sex work as a form of resisting being labeled as a prostitute by oneself or others (Browne & Minichiello, 1996). These men adopt a “sex as work” perspective, framing themselves as escorts, companions, or body workers/masseurs, or even adopting the term “sex worker.” Such men emphasize that they are professionals and entrepreneurs who perform a valuable service for their clients (Browne & Minichiello, 1996; Koken et al., 2004; Mclean, 2012; Morrison &Whitehead, 2005). Morrison and Whitehead (2005) describe this framing of escorting as a career as an identity-management strategy that men employ to resist the stigma associated with sex work. As part of this professionalization of sex work, men create and maintain personal boundaries to differentiate “work sex” from “personal sex” (Browne and Minichiello, 1996; McLean, 2012). These internal stigma-resisting and coping strategies help men create a meaningful self-narrative about their participation in the sex industry.

Whatever MSWs may think of their own work, they must confront the stigma associated with being a prostitute when faced with answering questions loved ones raise about their work. Erving Goffman’s (1963) classic theory of stigma management provides a useful framework for interpreting men’s strategies for managing the disclosure of sex work to loved ones (Koken et al., 2004). Some men choose “passing” as their preferred coping strategy, telling no one of their work and creating a cover story if necessary. More commonly, men choose to tell some trusted others—often other sex workers—about their work, a strategy Goffman termed “covering” (Koken et al., 2004; Mclean, 2012). Men rarely report openly identifying as a sex worker, using a stigmaresistance strategy to shift the social meaning of sex work away from stigma, an act similar to what feminist scholar Rhoda Unger terms “positive marginality” (Koken, Bimbi, & Parsons, 2007). Unfortunately, many male escorts—particularly those who work online and independently—report feelings of social isolation due to the perceived need to keep their work secret from loved ones and community members (Koken et al., 2004; McLean, 2012; Mclean, 2012). Conversely, a study of a rural escort agency in the northeastern United States (Smith et al., 2013; Smith & Seal, 2008) found that the escort agency structure and physical space (a large home where men worked and sometimes resided) facilitated socializing with other MSWs and even peers, thereby increasing men’s access to social support.

Studies of stigma coping and resistance strategies have primarily investigated samples of MSWs who enjoy a certain degree of economic and social-class privilege. Men in most of these samples (Koken et al., 2004; Mclean, 2012; Morrison & Whitehead, 2005) worked independently, advertising through the Internet in developed Western nations such as the United States, Australia, and Canada. However, modern research focusing on street-based MSWs and those in developing nations tends to be more epidemiologically focused (Minichiello, Scott, & Callander, 2013); when psychological issues are measured, they typically are limited to experiences of trauma and violence. It is difficult to say if the stigmamanagement and resistance strategies described above (Browne & Minichiello, 1996; Koken et al., 2004; Mclean, 2012; Morrison & Whitehead, 2005) would generalize to men working in less privileged circumstances. However, the stigma attached to men’s participation in prostitution appears to be pervasive, crossing boundaries of geography and social class.

Mental Health Issues among Male Sex Workers

The literature on stigma and coping among MSWs is part of a larger body of work exploring mental health among people with “concealable stigma,” including but not limited to being a sex worker, a sexual minority (such as being gay or preferring less common sexual activities such as domination/submission), infected with HIV, or having other concealable, potentially discrediting characteristics. Thus, MSWs, like others with concealable stigmas, may potentially be more vulnerable to mental health problems (Cole, Kemeny, Taylor, & Visscher, 1996; Frable, Platt, & Hoey, 1998; Huebner, Davis, Nemeroff, & Aiken, 2002; Meyer, 2013; Shehan et al., 2003). These poor mental health outcomes may be related to the chronic stress and social marginalization often experienced by those who engage in stigma-management strategies (Link & Phelan, 2006; Meyer, 2013) and have limited access to social support from peers and loved ones, who frequently are not aware of their stigma (Frable et al., 1998).

Although cross-sectional samples make it difficult to identify the cause or predictor of mental health outcomes, it does appear that MSWs as a population are more vulnerable to mental health problems. This has been found even among relatively privileged samples of men. In one sample of 30 male escorts working at a rural escort agency in the northeastern United States (Smith & Seal, 2007), high rates of psychiatric distress were reported, with 14 of the 30 men scoring in the clinical range. Among street-based MSWs, rates of mental health problems are even higher. One sample of 32 MSWs in a northeastern U.S. urban center reported that over one-third of the sample had been diagnosed with depression at some point, with street-based MSWs the most likely to report a history of inpatient psychiatric treatment (Mimiaga et al., 2009). Among a small sample (n = 12) of street-based MSWs in Dublin, Ireland, half reported suicidal ideation and two-thirds were experiencing severe to moderate levels of depression (McCabe et al., 2011).

Substance Use and Male Sex Work

Given the high rates of mental health issues reported across samples of MSWs, it is unsurprising that substance use and abuse appear to be higher among this population as well. Much of the research on substance use among MSWs concerns its associations with sexual risk behavior (for exploration of this phenomenon, see David Bimbi’s chapter in this volume on MSWs and public health). Again, this focus reflects a larger concern with MSWs as a public health issue, rather than with the mental health of sex workers themselves.

For MSWs, alcohol and/or drug use may facilitate encounters with clients (Bimbi, Parsons, Halkitis, & Kelleher, 2001; Mimiaga et al., 2009) or be used to cope with negative emotions related to performing sex work (Mimiaga et al., 2009). Conversely, sex sometimes may be exchanged for drugs or to earn money to buy drugs, particularly among street-based samples (McCabe et al., 2011; Mimiaga et al., 2009). Men also may use alcohol or drugs for relaxation and entertainment just as others do: use of substances by MSWs should not be problematized per se or immediately assumed to be “caused” by being a sex worker; nor should reporting use of alcohol or drugs (without a measure of substance dependence) be misconstrued as evidence of addiction. However, given the limitations of most research with MSWs (small, nonrandomly selected, cross-sectional samples), it can be difficult to tease out causal relationships (if any do exist) between substance use/abuse and sex work among men.

While substance use among MSWs appears relatively common across venues (e.g., the street, Internet), the types of substances used and patterns of use differ between samples. For example, in one study comparing street-based to Internet-based MSWs in a northeastern U.S. urban center, high rates of alcohol problems were reported, with 50 percent of men screening as potentially alcohol dependent (Mimiaga et al., 2009). Similar findings were reported among a small sample of 12 MSWs working on the streets of Dublin, where more than half the men screened as potentially alcohol dependent (McCabe et al., 2011). Men working the street in a large northeastern U.S. city were more likely to report cocaine or crack use and a history of substance abuse treatment, while Internet-based escorts reported more crystal methamphetamine use, perhaps reflecting the social framing of this as a “club drug” known for enhancing sexual experiences among men who have sex with men (Mimiaga et al., 2009). Among men working at an escort agency in a rural northeastern U.S. town (Smith & Seal, 2007), over one-fourth of the sample reported having a substance problem, and over one-third reported having had such problems in the past. While these samples draw from very different populations and are not large enough to generalize to MSWs globally, they indicate that substance use problems may be very common among MSWs across venues, although differences in the substances abused may emerge between street-based men and those who are escorts, based on local trends and availability of illicit substances.

Other books

May the Best Man Win by M.T. Pope

Clickers vs Zombies by Gonzalez, J.F., Keene, Brian

Cinders and Ashes by King, Rebecca

Black by T.l Smith

Countdown to Armageddon by Darrell Maloney

A Walk Through Fire by Felice Stevens

Brainquake by Samuel Fuller

Word of Honor by Nelson Demille

The Rise of David Levinsky by Abraham Cahan

Fury and the Power by Farris, John