Male Sex Work and Society (50 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

Nevertheless, the reality is that there are fewer specialist services available for men engaging in sex work than for women; this is especially true outside major urban centers. Existing services generally offer crisis-intervention packages that attend to sex workers’ immediate needs, such as homelessness, access to funds, health care, support with criminal justice system issues, as well as intervention work and harm minimization that is focused on sex work (see, e.g., Irving & Laing, 2013). However, Gaffney (2012) also identified a number of key services needed specifically by men working in off-street contexts, including those related to sexuality/gender identity, immigration status, dealing with the stigma of sex work, competing for clients in a saturated market, life skills, having a large number of sexual partners (paying and nonpaying), and the pressure to engage in “bareback” sex (i.e., without a condom).

The penultimate section of this chapter adds to the existing body of work by documenting the specialist service needs of male sex workers, and it details the findings of a survey exploring the needs of men working in the sex industry in the UK.

Male Sex Work: A Needs Assessment

The needs of men who sell sex are contingent and multiple. There is a range of intervention approaches; men will access different services for different needs at different times in their lives, and some will never access services. Those who do must receive services that meet their specific needs if the intervention is to be effective. One way services can reach out to men selling sex is through the provision of resources. For example, the UK Network of Sex Work Projects guide

Sorted Men

(see

figure 11.1

) is a downloadable resource for men who sell sex. This type of resource is especially useful for men working in areas where specialist service provision does not exist.

Sorted Men

(see

figure 11.1

) is a downloadable resource for men who sell sex. This type of resource is especially useful for men working in areas where specialist service provision does not exist.

Justin Gaffney and SohoBoyz conducted a needs assessment of MSWs that was funded by the Department of Health (see

figure 11.2

).

4

They collected data from a survey completed by men working in various contexts between April and September 2009; 109 surveys were filled out, 63 were completed fully, 46 only partially, as some people chose not to answer some questions. Participation in the survey was promoted through specialist service providers in Manchester, Brighton, and London, via the SohoBoyz website, and through advertisements in

Gay Times

and

Boyz

magazine.

figure 11.2

).

4

They collected data from a survey completed by men working in various contexts between April and September 2009; 109 surveys were filled out, 63 were completed fully, 46 only partially, as some people chose not to answer some questions. Participation in the survey was promoted through specialist service providers in Manchester, Brighton, and London, via the SohoBoyz website, and through advertisements in

Gay Times

and

Boyz

magazine.

The surveys were completed in a variety of settings, including at projects that support sex workers and in the places the men worked, including flats, brothels, parlors, streets, bars and clubs, and at home. Those who completed the survey worked in a range of settings, including brothels and parlors and the streets; some participants engaged in escort work both independently and via agencies; some men also worked in pornography, offered massage, and worked opportunistically in public sex environments. Those who took part were offered a Sohoboyz condom bag as a thank-you. The survey included 113 questions that covered basic demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, relationship status), reasons for engaging in sex work, involvement with pornography, clients, sexual health, mental health, education and life skills, drug and alcohol use, access to specialist services, body image, and plans to exit sex work. What follows is a snapshot of the key findings.

Demographics

The participants were predominantly male (97 percent); there was one transgender respondent, and another identified as “queer, male bodied.” The age range was 17-55, with a mean age of 26, and the majority filled out the survey in three cities, London, Manchester, and Brighton. A majority (72 percent) self-identified as White British, White Irish, or White “Other,” while the remaining respondents identified as Black or as being from an Asian country or from Europe. Most identified as homosexual (72 percent), but some identified as heterosexual and bisexual. Two people identified as queer and one as “a man who loves other men.” The majority were born in the UK (82 percent); the others were from Spain, Venezuela, Poland, Portugal, Germany, the Czech Republic, and Russia. At the time of the survey, more than 25 percent of participants were in a relationship with a man and 16 percent with a woman; 21 said their partner was aware of their sex work, and more than half of these said that engaging in sex work had caused arguments in their relationship. Only seven participants said they had children.

The most common reason participants gave for entering sex work was economics and because it was their choice to sell sex. Others were offered money in a public sex environment and/or entered sex work through opportunistic methods, such as being introduced to sex work by a partner/boyfriend/girlfriend/relative or responding to an advertisement. Six people said they started selling sex because they had no money, were introduced by “other guys,” or were desperate and homeless, as these two participants explained:

I had no money and no accommodation in a city I knew nothing about. I met a man on the street, we started talking, and in exchange for housing me, he wanted me to give [him] sexual services for free.I was working as a waiter in [a private members club in] London and being paid poor money and feeling very alienated and lonely as a gay man. I saw an article in the paper about sex workers in [a known area] and I felt drawn to what could constitute more of gay community—at least I judge that now in retrospect. I was also desperate for money in a context that was not homophobic.

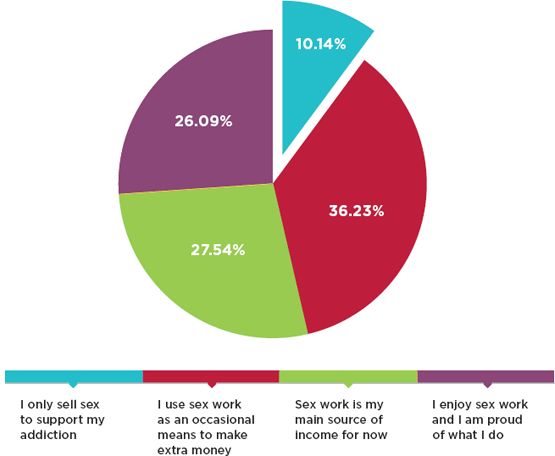

FIGURE 11.3

How Participants Describe Their Involvement in Sex Work (n = 69)

Participants were also asked to describe their involvement in sex work. As seen in

figure 11.3

, most participants (36 percent) used sex work as an occasional means to make money, 28 percent classed their sex work as a main source of income “for now,” and 26 percent said they enjoyed sex work. Only 10 percent reported that they sold sex to support an addiction; in fact, many participants said they did not use drugs at all (38 percent) or that their drug use was not a problem for them (42 percent). Only five said their drug use was a problem and that they would like help.

figure 11.3

, most participants (36 percent) used sex work as an occasional means to make money, 28 percent classed their sex work as a main source of income “for now,” and 26 percent said they enjoyed sex work. Only 10 percent reported that they sold sex to support an addiction; in fact, many participants said they did not use drugs at all (38 percent) or that their drug use was not a problem for them (42 percent). Only five said their drug use was a problem and that they would like help.

Most respondents stated that they drank in moderation; 42 percent stated that they only had one or two drinks at a time, and 20 percent said they drank enough to feel drunk. Only six participants said they drank too much and that it was a concern, but not one said they wanted help with this issue. This reflects the broader theme running through the data that most men surveyed made a choice to sell sex at that time of their lives for financial reasons rather than having to support an alcohol or drug addiction.

Education, Life Skills, and Income

Participants were asked in the survey about their education and life skills. The findings revealed that nearly half of participants were university or college graduates, and a five had postgraduate education, including an MA (or equivalent) and/or a PhD. A further 35 percent had only completed a secondary education, four had completed primary/elementary school, and six had no education. Several respondents did show an interest in developing life skills and furthering their education, including attending university (25 percent) or attending classes based on personal interests (26 percent), such as photography; an equal number wanted to improve their education more generally. Others said they would like to develop life skills (e.g., money management, 20 percent), take some sort of practical class (e.g., computing, 15 percent) or vocational course (e.g., plumbing, 13 percent), and several wanted to take a course to improve their English. One participant stated that he would like to go to college to help facilitate a move abroad, while another saw education as an opportunity to change his lifestyle: “I would just like 2 sort my head out an look 4 a job like a normal person I hate da life I av now its horrible I just wish things were different.” Only one-quarter of respondents had no educational or vocational aspirations.

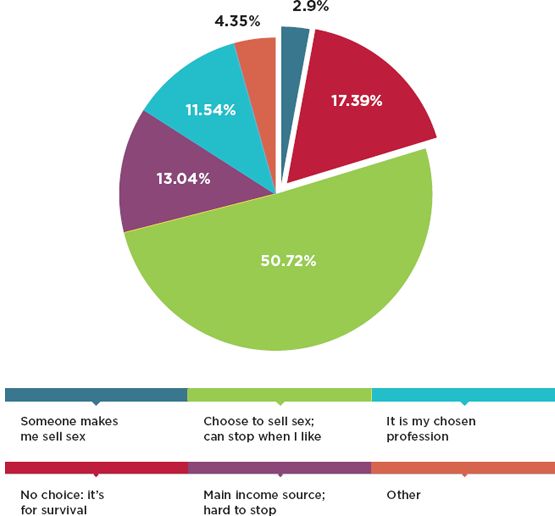

Half of the participants said they sold sex to supplement their income and that they could stop when they chose to (see

figure 11.4

). The second largest group (17 percent) said that engaging in sex work was central to their survival at that time, so they had no choice and did not enjoy it. Although this statement could relate to men engaged in street or opportunistic sex work, the data revealed diverse responses:

figure 11.4

). The second largest group (17 percent) said that engaging in sex work was central to their survival at that time, so they had no choice and did not enjoy it. Although this statement could relate to men engaged in street or opportunistic sex work, the data revealed diverse responses:

My situation means that I currently sell sex to survive. As I have a broken employment history, I find it difficult to seek suitable other work that would satisfy me. I am intelligent & have abilities, but history, qualifications & references are lacking, so work that I can achieve is often below what I am capable of. I sell sex as I can offer a good service with this. I would like to find a way out of selling sex, but feel trapped with a lack of options of what else to do.

FIGURE 11.4

Responses on Income, Choice, and Sex Work (n = 69)

Nearly 15 percent said that their engagement in sex work was voluntary and that sex work was their main source of income and it would be difficult to stop; 12 percent said they enjoyed sex work and were in control of their engagement; and just 3 percent revealed that someone was making them sell sex. One participant commented, “It’s a supplement, but I am independent, in control and I enjoy it.” Another said,

I am also dissatisfied with this aspect of my income and feel a bit trapped in it—it’s “what I know” and relatively easy to get income—albeit sometimes with psychological cost … Sometimes I do enjoy aspects of my work and can see its value—especially in terms of the massage element and in a therapeutic element, to tantric massage where one is involved in healing.

In response to questions about how participants spent their income when they started to sell sex, for nearly half the most common answer was on their social life, going out, and luxuries; the next most common was on household expenses (41 percent), savings (22 percent), and drugs (19 percent). As levels of drug dependency were low in the sample, much of this spending is likely to have been on drugs for recreational use. About one-fifth used income from sex work to supplement their existing income, the rest used it to support family, children, and/or a partner, and to pay for studies and health care; one person said they were made to work for someone else. Several commented that they used the money to pay debts, the mortgage, accommodation costs, food, and other bills. One participant commented:

When I started I could make 100 pounds a day—which was not bad in the ’70s—but most of it went on funding my life in gay night clubs—which was the only community I knew or felt attracted to. Later money went on getting an apartment in [London], funding therapy and lots of organic food.

When asked if sex work was their main source of income in the past four weeks, 50 percent said yes and 46 percent said no; the rest preferred not to answer. Other sources of income for the participants included fulltime professional jobs, service and care-type jobs, cash-in-hand type work, and selling drugs.

Clients, Sexual Health, and Exiting Sex Work

Other books

La cabeza de la hidra by Carlos Fuentes

If Wishes Were Horses by Robert Barclay

Among the Nameless Stars by Diana Peterfreund

Stirred Up by Isabel Morin

Island Girls by Nancy Thayer

Send in the Clowns, a Detective Mike Bridger novel by Mark Bredenbeck

Newcomers by Lojze Kovacic

Out of Alice by Kerry McGinnis

Evolver: Apex Predator by Lewis, Jon S., Denton, Shannon Eric, Hester, Phil, Arnett, Jason