Mark Griffin (44 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

For Minnelli, the decor helped shape the story as much as the dialogue or action—even in a “Western.” “I spent ages on that room. I’m a great furniture mover,” Vincente said of designing Mitchum’s over-the-top hunter’s den.

9

Surrounded by bear-skin rugs, bloodhounds, and mounted trophy heads, Theron is carefully framed by Minnelli as though he’s about to become his father’s next prey. As the camera pans across Mitchum’s lair, one can sense Vincente’s delight in decorating a room in such a flagrantly barbaric style. And there’s no way to miss the point that Theron is about to be indoctrinated into the world of Real Men.

9

Surrounded by bear-skin rugs, bloodhounds, and mounted trophy heads, Theron is carefully framed by Minnelli as though he’s about to become his father’s next prey. As the camera pans across Mitchum’s lair, one can sense Vincente’s delight in decorating a room in such a flagrantly barbaric style. And there’s no way to miss the point that Theron is about to be indoctrinated into the world of Real Men.

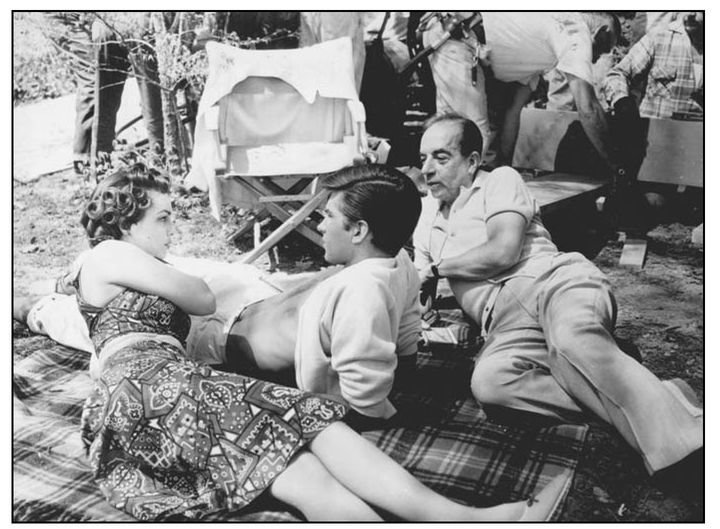

Three’s Company: George Hamilton shares a blanket with co-star Luana Patten and director Minnelli on location for

Home from the Hill

, 1959. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Home from the Hill

, 1959. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Is it purely coincidental that

Tea and Sympathy

,

Some Came Running

, and

Home from the Hill

all focus on men grappling with what might be termed “male identity issues”? Those who consider studio system directors like Minnelli nothing more than factory foremen would dismiss the similar storylines as pure happenstance—the sort of thing that was “in the air” at the time. Auteurists, devotees of

Cahiers du Cinéma

, and Minnelli disciples prefer to see the links as part of a grander plan. It would appear that Vincente was seeking out and shaping properties that explored his theme of choice: a repressed misfit, unable to seek solace from his family or from the world around him, must go within in order to heal himself. This would be the sort of thing writers David Siegel and Scott McGehee would describe as “the peculiar sub-genre of the Minnelli Male Melodrama. . . . Perhaps it is something about the weird genre/gender conflict of a man telling a story about men in this particularly feminine idiom that gives these films their disturbing and psychotic beauty.”

10

Tea and Sympathy

,

Some Came Running

, and

Home from the Hill

all focus on men grappling with what might be termed “male identity issues”? Those who consider studio system directors like Minnelli nothing more than factory foremen would dismiss the similar storylines as pure happenstance—the sort of thing that was “in the air” at the time. Auteurists, devotees of

Cahiers du Cinéma

, and Minnelli disciples prefer to see the links as part of a grander plan. It would appear that Vincente was seeking out and shaping properties that explored his theme of choice: a repressed misfit, unable to seek solace from his family or from the world around him, must go within in order to heal himself. This would be the sort of thing writers David Siegel and Scott McGehee would describe as “the peculiar sub-genre of the Minnelli Male Melodrama. . . . Perhaps it is something about the weird genre/gender conflict of a man telling a story about men in this particularly feminine idiom that gives these films their disturbing and psychotic beauty.”

10

For everything that works in

Home from the Hill

(Mitchum, Bronislau Kaper’s moving score), there are key elements that do not (the contrived

story line is simply too much, and there’s a tendency toward pop-eyed melodramatics). Although Minnelli’s direction is assured and he’s clearly interested, it takes an awfully long time—150 minutes, in fact—to tell a story that could have easily been wrapped up at the two-hour mark. But this Southern Gothic soap opera seemed to encourage Vincente’s penchant for excess.

Home from the Hill

(Mitchum, Bronislau Kaper’s moving score), there are key elements that do not (the contrived

story line is simply too much, and there’s a tendency toward pop-eyed melodramatics). Although Minnelli’s direction is assured and he’s clearly interested, it takes an awfully long time—150 minutes, in fact—to tell a story that could have easily been wrapped up at the two-hour mark. But this Southern Gothic soap opera seemed to encourage Vincente’s penchant for excess.

“Under Vincente Minnelli’s direction it is garishly overplayed,” wrote

New York Times

critic Bosley Crowther, who dismissed

Home from the Hill

as “aimless, tedious and in conspicuously doubtful taste,” while

Commonweal

found Vincente’s staging throughout the film “particularly uneven.” “Some scenes,” wrote the reviewer, “are straight overacted melodrama, and then again, some, like the hunting and chase sequences in the woods . . . are done with extraordinary strength and beauty.”

11

Despite the mixed reception,

Home from the Hill

would prove to be the last Minnelli movie to turn a respectable profit ($5,610,627).

New York Times

critic Bosley Crowther, who dismissed

Home from the Hill

as “aimless, tedious and in conspicuously doubtful taste,” while

Commonweal

found Vincente’s staging throughout the film “particularly uneven.” “Some scenes,” wrote the reviewer, “are straight overacted melodrama, and then again, some, like the hunting and chase sequences in the woods . . . are done with extraordinary strength and beauty.”

11

Despite the mixed reception,

Home from the Hill

would prove to be the last Minnelli movie to turn a respectable profit ($5,610,627).

29

Better Than a Dream

“NOTHING EVER TERRIFIED ME as much as that switchboard,” Judy Holliday would recall of her days keeping up with the calls as an operator at Orson Welles’s Mercury Theatre. Despite her on-the-job jitters, Holliday’s switchboard experience (such as it was) would prove invaluable years later when she opened on Broadway in

Bells Are Ringing

.

Bells Are Ringing

.

The hit 1956 musical was written by Holliday’s old friends, Betty Comden and Adolph Green, with music composed by Jule Styne. In a Tony Award- winning tour de force, Holliday starred as Ella Peterson, a kind of answering-service oracle who is everything to everybody. On the front lines at the Manhattan-based “Susanswerphone,” Ella not only fields calls and relays messages but serves up a dazzling array of over-the-phone alter egos to keep her subscribers happy. If some mother’s little darling refuses to eat his spinach, Ella slips into her most convincing Santa Claus and gives junior a talking to. If playboy playwright Jeffrey Moss is sleeping off a severe case of writer’s block, Ella turns herself into the unfailingly supportive “Mom” and makes sure Shakespeare gets his daily wake-up call. But when it comes time for the unconfident Ella to deal with people face to face, it’s one wrong number after another.

According to Betty Comden, the idea for the show was inspired by a rude awakening:

I didn’t have an answering service and I asked Adolph what his service was like and he said, “I don’t know. Let’s find out where it is!” We found out it

was just around the corner from where he lived on East 53rd Street. We pictured that it would be this sort of shiny, stainless steel place with rows and rows of telephones and glamorous girls sitting at them. Instead, it was in this terrible ramshackle building, down a couple of little cellar steps, and it was really depressing as hell. We walked into this incredibly messy room that was unpainted and peeling and in the middle of all of it sat this one very fat lady at a switchboard saying, “Gloria Vanderbilt’s residence. . . .” We looked at each other and said, “Now here’s an idea for a show!”

1

was just around the corner from where he lived on East 53rd Street. We pictured that it would be this sort of shiny, stainless steel place with rows and rows of telephones and glamorous girls sitting at them. Instead, it was in this terrible ramshackle building, down a couple of little cellar steps, and it was really depressing as hell. We walked into this incredibly messy room that was unpainted and peeling and in the middle of all of it sat this one very fat lady at a switchboard saying, “Gloria Vanderbilt’s residence. . . .” We looked at each other and said, “Now here’s an idea for a show!”

1

Hollywood was notorious for not allowing Broadway stars to recreate their acclaimed stage roles on film—Mary Martin, Ethel Merman, and Julie Andrews had all been passed over when

South Pacific

,

Gypsy

, and

My Fair Lady

turned up on movie screens. Holliday proved to be the exception to the rule as she already had a cinematic track record, having won an Oscar and enormous acclaim for her performance as Billie Dawn in

Born Yesterday

. The film’s director, George Cukor, considered Holliday “A true artist. . . . She made you laugh, she was a supreme technician, and then suddenly you were touched.”

2

Holliday was highly regarded off screen as well. Many of her colleagues remembered her as an endearing presence and an exceedingly generous performer. Despite her tremendous talent, though, her insecurities and self-doubt could be crippling, and Minnelli was about to experience her neurotic side at full volume.

South Pacific

,

Gypsy

, and

My Fair Lady

turned up on movie screens. Holliday proved to be the exception to the rule as she already had a cinematic track record, having won an Oscar and enormous acclaim for her performance as Billie Dawn in

Born Yesterday

. The film’s director, George Cukor, considered Holliday “A true artist. . . . She made you laugh, she was a supreme technician, and then suddenly you were touched.”

2

Holliday was highly regarded off screen as well. Many of her colleagues remembered her as an endearing presence and an exceedingly generous performer. Despite her tremendous talent, though, her insecurities and self-doubt could be crippling, and Minnelli was about to experience her neurotic side at full volume.

From the moment she signed a contract with MGM to appear in a Freed-produced, Minnelli-directed version of

Bells Are Ringing

, Holliday seemed to have second thoughts. The comedienne agonized over what she perceived to be some of the weaknesses in the screenplay. In reviewing the stage show, the same Brooks Atkinson who had saluted Holliday and the sprightly score had grumbled about “one of the most antiquated plots of the season.”

3

Although Comden and Green had handled the adaptation chores themselves, Holliday felt that in attempting to open up the story for the screen, they’d only succeeded in making the show longer—not more cinematic. Would the flimsy plot become even more conspicuous when it was magnified on a movie screen? This got the slightly overweight star to thinking about how

she

would look on a movie screen—blown up to CinemaScope proportions, no less. With each passing day, Holliday’s doubts and fears multiplied.

Bells Are Ringing

, Holliday seemed to have second thoughts. The comedienne agonized over what she perceived to be some of the weaknesses in the screenplay. In reviewing the stage show, the same Brooks Atkinson who had saluted Holliday and the sprightly score had grumbled about “one of the most antiquated plots of the season.”

3

Although Comden and Green had handled the adaptation chores themselves, Holliday felt that in attempting to open up the story for the screen, they’d only succeeded in making the show longer—not more cinematic. Would the flimsy plot become even more conspicuous when it was magnified on a movie screen? This got the slightly overweight star to thinking about how

she

would look on a movie screen—blown up to CinemaScope proportions, no less. With each passing day, Holliday’s doubts and fears multiplied.

In a script conference with Minnelli and Freed, Holliday shared her thoughts on how the screenplay might be improved. Although Freed acknowledged that Holliday had “a few good suggestions,” he dismissed her concerns as “nothing monumental.”

4

Still, the star fretted over the fact that

little was being done to transform an intimate theater piece into a wide-screen event. As Holliday told

Cosmopolitan

: “Of course, lots of things have to be changed when a stage show is filmed. And should be, I think.”

5

Like the leading man, for example.

4

Still, the star fretted over the fact that

little was being done to transform an intimate theater piece into a wide-screen event. As Holliday told

Cosmopolitan

: “Of course, lots of things have to be changed when a stage show is filmed. And should be, I think.”

5

Like the leading man, for example.

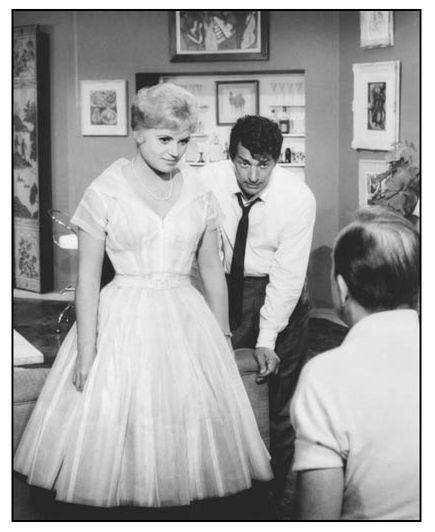

Judy Holliday and Dean Martin in conference with their director on the set of

Bells Are Ringing

. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Bells Are Ringing

. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Reportedly, Holliday had had an affair with her Broadway

Bells

costar, Sydney Chaplin. Despite the positive notices for his stage portrayal, Chaplin would not be invited to re-create his role on film. For one thing, his fling with Holliday had ended badly. But even more important to MGM was the fact that his name meant next to nothing to moviegoers. Instead, Dean Martin was cast as the procrastinating playwright Jeff Moss, or “Plaza O-double-four-double-three,” as he’s known on the switchboard. As principal photography began in October 1959, Holliday feared that Martin, like Minnelli, was sleepwalking his way through

Bells Are Ringing

—though Dino’s laissez-faire attitude certainly suited the character and his easygoing demeanor offered the perfect contrast to Holliday’s high-spirited intensity.

Bells

costar, Sydney Chaplin. Despite the positive notices for his stage portrayal, Chaplin would not be invited to re-create his role on film. For one thing, his fling with Holliday had ended badly. But even more important to MGM was the fact that his name meant next to nothing to moviegoers. Instead, Dean Martin was cast as the procrastinating playwright Jeff Moss, or “Plaza O-double-four-double-three,” as he’s known on the switchboard. As principal photography began in October 1959, Holliday feared that Martin, like Minnelli, was sleepwalking his way through

Bells Are Ringing

—though Dino’s laissez-faire attitude certainly suited the character and his easygoing demeanor offered the perfect contrast to Holliday’s high-spirited intensity.

Convinced that she was starring in a mediocre retread of her Broadway show, Holliday asked to be released from her contract and even offered to hand back her salary if Minnelli would start over with, say, Shirley MacLaine manning the switchboard. The studio did not take Holliday up on her offer.

She would have to continue. She even made her reservations public, telling reporter Jon Whitcomb: “I’ve done four pictures with George Cukor, and he’s a perfectionist. I’m afraid Arthur Freed and Mr. Minnelli are very easy to please. They don’t mind okaying things that strike me as only half right. If anybody knows the values in this play, I do. After living in it for three years, I’m the final authority on what lines ought to get laughs and how to get them.”

6

She would have to continue. She even made her reservations public, telling reporter Jon Whitcomb: “I’ve done four pictures with George Cukor, and he’s a perfectionist. I’m afraid Arthur Freed and Mr. Minnelli are very easy to please. They don’t mind okaying things that strike me as only half right. If anybody knows the values in this play, I do. After living in it for three years, I’m the final authority on what lines ought to get laughs and how to get them.”

6

As Holliday biographer Gary Carey noted, “Vincente Minnelli was surprised to find he couldn’t gain Holliday’s confidence. . . . Minnelli did his best to reassure her, but he failed to win Judy’s confidence simply because she was convinced that the entire concept of the film was hopelessly, irredeemably wrong.” As outrageously talented and insecure as that other Judy, Holliday also shared Garland’s susceptibility to illness—either real or imagined. Over the course of a tense production, Holliday suffered from laryngitis, bursitis, bladder problems, and a kidney infection, all of which may have been early indications of the far more serious health problems ahead for Holliday. Or were these physical manifestations of her fears? “I kept reassuring her, but Judy was a constant worrier,” Minnelli said of Holliday, likening her to Fred Astaire. Both performers were exacting perfectionists whose work appeared effortless on screen. It was ironic that two of the most talented stars in the business were rarely satisfied with their own efforts.

7

7

Wisely, Minnelli lets his camera linger on his leading lady throughout

Bells Are Ringing

. Blessed with undeniable magnetism and unsurpassed comedic timing, Holliday is the heart and soul of the whole picture. Just as

Funny Girl

wouldn’t have been much minus Barbra Streisand,

Bells Are Ringing

is totally dependent on its shining star for life support.

Bells Are Ringing

. Blessed with undeniable magnetism and unsurpassed comedic timing, Holliday is the heart and soul of the whole picture. Just as

Funny Girl

wouldn’t have been much minus Barbra Streisand,

Bells Are Ringing

is totally dependent on its shining star for life support.

Whether belting out the ultimate 11 o’clock number, “I’m Going Back” (“. . . Where I can be me at the Bonjour Tristesse Brassiere Company”) or poignantly realizing that “The Party’s Over,” Holliday dazzles with a superlative musical-comedy performance that’s charged with a genuine warmth and vulnerability. Although Rosalind Russell or Shirley MacLaine could have played Ella Peterson and come through with an effective comedic performance, the endearingly neurotic switchboard operator is clearly a role that Holliday was born to play. “The picture owes more to Miss Holliday than it does to its authors, its director or even to Alexander Graham Bell,” Bosley Crowther declared in the

New York Times

.

8

New York Times

.

8

Though the film was a personal triumph for Holliday and the Comden and Green score is first rate, some of the star’s concerns about the production turned out to be well founded. As the finished film reveals, Minnelli made only marginal attempts to open the story up and liberate it from its theatrical

roots. And why was CinemaScope—a process better suited to breathtaking, panoramic vistas—foisted upon an intimate musical comedy set largely indoors and in confined quarters?

roots. And why was CinemaScope—a process better suited to breathtaking, panoramic vistas—foisted upon an intimate musical comedy set largely indoors and in confined quarters?

None of this phased the

Hollywood Reporter

: “It is a better musical on screen than it was on stage,” decided James Powers. “For MGM, ‘Bells’ will ring loud and long, in the friendly clang of the box office cash register.” This proved to be the case when the picture opened at Radio City Music Hall in June. Later that summer, MGM’s accountants were able to proudly report: “

Bells Are Ringing

joined an elite company of blockbuster films when it topped the one million dollar mark at the Radio City Music Hall box office.”

9

Hollywood Reporter

: “It is a better musical on screen than it was on stage,” decided James Powers. “For MGM, ‘Bells’ will ring loud and long, in the friendly clang of the box office cash register.” This proved to be the case when the picture opened at Radio City Music Hall in June. Later that summer, MGM’s accountants were able to proudly report: “

Bells Are Ringing

joined an elite company of blockbuster films when it topped the one million dollar mark at the Radio City Music Hall box office.”

9

Other books

Kinky by Elyot, Justine

The Spook 9 - Slither's tale by Delaney Joseph

Silent as the Grave by Bill Kitson

Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov

Branded: You Own Me & The Virgin's Night Out by Walker, Shiloh

Parlor Games by Maryka Biaggio

Hewitt: Jagged Edge Series #1 by A.L. Long

Conquistadors of the Useless by Roberts, David, Terray, Lionel, Sutton, Geoffrey

The Beauty Series by Skye Warren