Mark Griffin (46 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

Brian Avery (best remembered for his role as Dustin Hoffman’s rival in

The Graduate)

, played Paul Lukas’s son in

Four Horsemen

. Avery recalled that Vincente made an indelible impression from the very first casting call:

The Graduate)

, played Paul Lukas’s son in

Four Horsemen

. Avery recalled that Vincente made an indelible impression from the very first casting call:

Mr. Minnelli wore these long-sleeved yellow cashmere sweaters and he had a twitch. Sometimes the sides of his cheeks would kind of twitch when he talked and he generally had a cigarette. He said to me, “What kind of parts do you specialize in?” And I said, “Sons.” So, he cast me and it was an extraordinarily wonderful experience. I got to spend five weeks on what was then and may still be the largest soundstage in the world, which was Stage 15 at MGM.

10

10

Apocalypse Now: Ingrid Thulin, Minnelli, and Glenn Ford on location for

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

in 1961. Pushed to the breaking point by her director, Thulin walked off the set. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

in 1961. Pushed to the breaking point by her director, Thulin walked off the set. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

On that stage, Avery and most of the principal players appeared in a dramatically charged dining-room sequence in which Heinrich von Hartrott (Karl Boehm) reveals that he is a Nazi and the major conflicts of World War

II are metaphorically played out as domestic drama. Although Avery was befriended by several of his veteran costars, his on-set experiences also included the inevitable dose of self-absorbed star behavior. “He was a piece of work,” Avery says of leading man Glenn Ford:

II are metaphorically played out as domestic drama. Although Avery was befriended by several of his veteran costars, his on-set experiences also included the inevitable dose of self-absorbed star behavior. “He was a piece of work,” Avery says of leading man Glenn Ford:

Glenn had read his own publicity, I guess. He was not friendly. The entire time I worked on the film—those five or six weeks—and sat across the table from him all day long, he never once greeted me or said, “Hello” or “Goodbye” or acknowledged my existence. Meanwhile, Charles Boyer is treating me like a son, I’m going to lunch with Lee J. Cobb all the time, . . . but Glenn Ford would sit and make jokes with Yvette Mimieux about some dwarf doing each of them under the table.

11

11

In sharp contrast, Avery found his director a thoroughgoing professional: “Mr. Minnelli ran the set very well. He was attentive. He was always there if you needed to speak to him about something. He was very interested in the women. I remember when Ingrid Thulin was on the set and he was very, very present to her.”

12

Some might say omnipresent.

12

Some might say omnipresent.

In late December, a crisis emerged when Ingrid Thulin, perilously close to having a nervous breakdown, walked off the set. Thulin was the latest in a long line of actors who found it difficult to adjust to Vincente’s unconventional and often quite literal hands-on approach. In a letter to Thulin’s agent, Paul Kohner, the actress’s husband, Harry Schein, detailed her miseries—not the least of which was a strained relationship with her director:

In Sweden, when a director shows an actor how to do a scene, how to act, one feels that either the director or the actor is an amateur. Since Ingrid not only likes Minnelli as a person but also admires his films and certainly knows that

he

is no amateur, she is now convinced that he considers

her

to be an amateur. She feels like a puppet or marionette instead of like the professional actress she is. . . . Ingrid has told me that Minnelli often wants her to look at him while he is showing her how to move, look, stand. She is then so occupied in studying his plastic and mimic movements that she loses not only her memory but also her concept of the scene. . . . Even if working conditions will be improved, I doubt that she will change her mind about her future activities in Hollywood.

13

he

is no amateur, she is now convinced that he considers

her

to be an amateur. She feels like a puppet or marionette instead of like the professional actress she is. . . . Ingrid has told me that Minnelli often wants her to look at him while he is showing her how to move, look, stand. She is then so occupied in studying his plastic and mimic movements that she loses not only her memory but also her concept of the scene. . . . Even if working conditions will be improved, I doubt that she will change her mind about her future activities in Hollywood.

13

On December 31, 1960 (the same day that Thulin’s husband wrote his letter), Minnelli was focused on someone other than his beleaguered leading lady. At the Palm Springs home of Joan Cohn (widow of Columbia Pictures

chief Harry Cohn), a justice of the peace married Vincente and Denise Giganti in a decidedly informal, off-the-cuff ceremony that seemed to recall the rushed nuptials in

The Clock

. Laurence Harvey, who had been considered for Ford’s

Four Horsemen

role, served as an attendant.

chief Harry Cohn), a justice of the peace married Vincente and Denise Giganti in a decidedly informal, off-the-cuff ceremony that seemed to recall the rushed nuptials in

The Clock

. Laurence Harvey, who had been considered for Ford’s

Four Horsemen

role, served as an attendant.

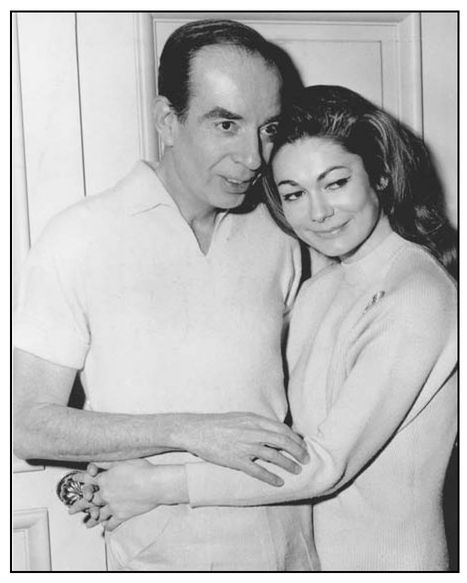

Vincente and the third Mrs. Minnelli, the colorful Denise Giganti. Rex Reed dubbed her “Queen of Group A,” the grand empress of Hollywood’s power elite. Those less enamored of the lady referred to her as “Denise, Inc.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

After returning to Beverly Hills with his charismatic third wife in tow, Vincente resumed work on

The Four Horsemen

. The only element of the film that received as much attention from Minnelli as Ingrid Thulin were the four horsemen themselves. At several points throughout the film, Tony Duquette’s andiron statues, representing Conquest, War, Pestilence, and Death, come to life, and the figures can be glimpsed galloping through an apocalyptic void. “All he worried about were the horses,” recalls Hank Moonjean, who served as the first assistant director in Paris. “It must have been at least five days to shoot that, maybe even longer, and it was so difficult. And the poor horses—we thought they were going to die. Extremely difficult. I don’t think any of that could ever be repeated.”

14

The Four Horsemen

. The only element of the film that received as much attention from Minnelli as Ingrid Thulin were the four horsemen themselves. At several points throughout the film, Tony Duquette’s andiron statues, representing Conquest, War, Pestilence, and Death, come to life, and the figures can be glimpsed galloping through an apocalyptic void. “All he worried about were the horses,” recalls Hank Moonjean, who served as the first assistant director in Paris. “It must have been at least five days to shoot that, maybe even longer, and it was so difficult. And the poor horses—we thought they were going to die. Extremely difficult. I don’t think any of that could ever be repeated.”

14

Following a preview in October 1961, substantial changes were made to the picture. “There was so much cutting and reshooting, they had to rerecord the entire score,” says George Feltenstein. Alex North’s underscoring was

tossed and replaced with some stunning new music by André Previn. It was also decided that Ingrid Thulin’s soft-spoken delivery and tenuous command of English were causing many of her lines to be lost. The orders came down that the actress would be dubbed, and her voice would be supplied by none other than Angela Lansbury. As Brian Avery remembered, “It was so remarkable that you had a Swede playing a French woman who is dubbed by an Englishwoman.”

15

tossed and replaced with some stunning new music by André Previn. It was also decided that Ingrid Thulin’s soft-spoken delivery and tenuous command of English were causing many of her lines to be lost. The orders came down that the actress would be dubbed, and her voice would be supplied by none other than Angela Lansbury. As Brian Avery remembered, “It was so remarkable that you had a Swede playing a French woman who is dubbed by an Englishwoman.”

15

John Gay believes that studio politics also played a part in the dubbing. “I never had any problems with Ingrid Thulin’s voice,” Gay says. “Of all the troubles we had going on, I thought Ingrid Thulin was wonderful. She was a terrific actress. I think it was MGM—the big wigs—I don’t think they could understand her.”

16

In fixating on

The Four Horsemen

’s auditory alterations, MGM seemed to be missing the big picture. For starters, Glenn Ford and Ingrid Thulin appeared to be mere acquaintances throughout the film instead of lovers.

16

In fixating on

The Four Horsemen

’s auditory alterations, MGM seemed to be missing the big picture. For starters, Glenn Ford and Ingrid Thulin appeared to be mere acquaintances throughout the film instead of lovers.

“The only memory I have—without going into anything that is just completely unkind—is my father saying that there was absolutely no chemistry between Glenn Ford and Ingrid Thulin,” says Paul Henreid’s daughter, Monika. “There are people who are on fire as lovers and you get what they call ‘movie magic,’ and there are people who play opposite each other and absolutely nothing happens. I think this is just a case where absolutely nothing happened.”

17

17

Nevertheless, MGM executives seemed to be looking at a completely different movie. “You could have heard a pin drop during the entire showing,” Metro executive Bob Mochrie reported to Vincente after a preview screening in late December. “I’m sure the public will be equally impressed and the word of mouth will be terrific. Pictures like this don’t come very often and I would like you to know that we will do all in our power to properly launch this great attraction.”

18

Mochrie was no prophet.

18

Mochrie was no prophet.

When it was all over—the 250,000 tons of military equipment, the 15,000 extras, the disembodied voice of Angela Lansbury—this $7 million “great attraction” just seemed to sit there on the screen. In his review for the

New York Herald Tribune

, Paul V. Beckley summed up the opinions of many when he wrote:

New York Herald Tribune

, Paul V. Beckley summed up the opinions of many when he wrote:

Warfare here is tidier than it ought to be, considering the basic point of the film. The prevailing tone is of genteel civility, sleek coiffures, delicately chosen furnishings. . . . Ingrid Thulin, who will be remembered as one of Ingmar Bergman’s group, here is over-powdered, over-cosmeticized to the virtual

exclusion of the vivid charm she possessed in the Bergman pictures. . . . I suspect any moviegoer could suggest a dozen films that in recent years have made the basic point this film undertakes but made it urgently, passionately and with deep conviction.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

fails precisely on this score.

19

exclusion of the vivid charm she possessed in the Bergman pictures. . . . I suspect any moviegoer could suggest a dozen films that in recent years have made the basic point this film undertakes but made it urgently, passionately and with deep conviction.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

fails precisely on this score.

19

“The whole thing is a mess,” says George Feltenstein. “But it didn’t have to be. Had Vincente been able to make the movie he wanted, I think it would have turned out beautifully.”

20

20

31

Don’t Blame Me

THE DECREE CAME DOWN from MGM’s new studio chief, Joseph Vogel: “MGM is now in the business of producing family pictures.” As the director of a Roman bacchanal that featured infidelity, attempted suicide, and an orgy, Minnelli had good to reason to be worried. It was unlikely that

Two Weeks in Another Town

would qualify as Vogel’s idea of wholesome family entertainment. In fact, Minnelli’s movie paled only in comparison to one other holdover from the studio’s previous administration: Stanley Kubrick’s

Lolita

, in which James Mason harbors an intense erotic obsession with teenager Sue Lyon. While Disney had ushered in the ’60s with

Pollyanna

and

The Parent Trap

, the MGM lion was now roaring over the likes of

Boys’ Night Out

, in which four men (three of them married) maintain a “bachelor pad” that comes complete with Kim Novak—though even that scenario seemed tame compared to Minnelli’s excursion into hedonistic excess.

Two Weeks in Another Town

would qualify as Vogel’s idea of wholesome family entertainment. In fact, Minnelli’s movie paled only in comparison to one other holdover from the studio’s previous administration: Stanley Kubrick’s

Lolita

, in which James Mason harbors an intense erotic obsession with teenager Sue Lyon. While Disney had ushered in the ’60s with

Pollyanna

and

The Parent Trap

, the MGM lion was now roaring over the likes of

Boys’ Night Out

, in which four men (three of them married) maintain a “bachelor pad” that comes complete with Kim Novak—though even that scenario seemed tame compared to Minnelli’s excursion into hedonistic excess.

Spurred on by the international success of Federico Fellini’s

La Dolce Vita

, which featured egoistic moviemakers squabbling against Roman backdrops, MGM’s former regime had pounced on a property with a similar setting and attendant freewheeling sexuality: Irwin Shaw’s coolly received 1960 novel,

Two Weeks in Another Town

. In Shaw’s novel, Jack Andrus—a physically and emotionally scarred NATO adviser—is summoned overseas to supervise the dubbing on a troubled movie that his mentor, Maurice Kruger, is directing in Rome. Once there, Andrus finds himself in the director’s chair, and his on-set battles are matched by his clashes with his capricious ex-wife, Carlotta.

La Dolce Vita

, which featured egoistic moviemakers squabbling against Roman backdrops, MGM’s former regime had pounced on a property with a similar setting and attendant freewheeling sexuality: Irwin Shaw’s coolly received 1960 novel,

Two Weeks in Another Town

. In Shaw’s novel, Jack Andrus—a physically and emotionally scarred NATO adviser—is summoned overseas to supervise the dubbing on a troubled movie that his mentor, Maurice Kruger, is directing in Rome. Once there, Andrus finds himself in the director’s chair, and his on-set battles are matched by his clashes with his capricious ex-wife, Carlotta.

After a self-imposed, three-year hiatus, John Houseman was once again producing pictures for MGM, and

Two Weeks in Another Town

seemed like the perfect project to welcome him back. Despite their skirmishes on

The Cobweb

and

Lust for Life

, Minnelli was Houseman’s first and only choice as director.

Two Weeks

(which would be shot partially on location in Rome) would reunite Vincente not only with Houseman but also with leading man Kirk Douglas,

au

screenwriter Charles Schnee, and composer David Raksin. With so much of the

Bad and the Beautiful

team reassembled, comparisons between that film and

Two Weeks in Another Town

were inevitable. In fact, it often seemed like the earlier picture was haunting this latest effort, which was not so much a sequel as a more oregano-flavored remake.

Two Weeks in Another Town

seemed like the perfect project to welcome him back. Despite their skirmishes on

The Cobweb

and

Lust for Life

, Minnelli was Houseman’s first and only choice as director.

Two Weeks

(which would be shot partially on location in Rome) would reunite Vincente not only with Houseman but also with leading man Kirk Douglas,

au

screenwriter Charles Schnee, and composer David Raksin. With so much of the

Bad and the Beautiful

team reassembled, comparisons between that film and

Two Weeks in Another Town

were inevitable. In fact, it often seemed like the earlier picture was haunting this latest effort, which was not so much a sequel as a more oregano-flavored remake.

Charles Schnee had worked wonders in terms of fleshing out George Bradshaw’s

Tribute to a Bad Man

and transforming it into

The Bad and the Beautiful

. But adapting Irwin Shaw’s solemn prose would prove to be more problematic. In early script conferences, it was decided that many of Shaw’s plot elements would be altered or streamlined for dramatic effect. It was Metro’s head of production Sol Siegel who suggested that audiences should be introduced to a Jack Andrus who has hit rock bottom—recovering from a nervous breakdown in a mental institution. This would prove to be one of the few good ideas a studio executive would have regarding

Two Weeks in Another Town

.

Tribute to a Bad Man

and transforming it into

The Bad and the Beautiful

. But adapting Irwin Shaw’s solemn prose would prove to be more problematic. In early script conferences, it was decided that many of Shaw’s plot elements would be altered or streamlined for dramatic effect. It was Metro’s head of production Sol Siegel who suggested that audiences should be introduced to a Jack Andrus who has hit rock bottom—recovering from a nervous breakdown in a mental institution. This would prove to be one of the few good ideas a studio executive would have regarding

Two Weeks in Another Town

.

After reviewing an initial draft of the script, Motion Picture Production Code supervisor Geoffrey Shurlock thought Schnee had remained far too faithful to Shaw’s text: “The portrayal of free and easy sexual intercourse is so graphically depicted herein that any pretense of presenting it in a moral light would appear to be almost ludicrous,” he wrote.

1

And during the Vogel regime, a sequence in which Jack Andrus was the headliner at an orgy would have been about as welcome as a stripper at a church social. Despite the fact that it had taken Schnee almost a year to knock out a treatment and two full drafts of

Two Weeks in Another Town

, he was asked to go back and reshape some of the material with an eye toward refashioning hard-core smut into soft-core smut.

1

And during the Vogel regime, a sequence in which Jack Andrus was the headliner at an orgy would have been about as welcome as a stripper at a church social. Despite the fact that it had taken Schnee almost a year to knock out a treatment and two full drafts of

Two Weeks in Another Town

, he was asked to go back and reshape some of the material with an eye toward refashioning hard-core smut into soft-core smut.

Other books

Stud by Cheryl Brooks

Truth Lake by Shakuntala Banaji

All of Me? The Trust Me? Trilogy by K E Osborn

Smashed by Mandy Hager

Waiting for Christopher by Louise Hawes

Robin's Reward (Bonita Creek Trilogy Book 1) by McCrary Jacobs, June

The Candy Cane Cupcake Killer by Livia J. Washburn

The Rogue Element (Scott Priest Book 1) by John Hardy Bell

Survivor: Steel Jockeys MC by Glass, Evelyn