Mark Griffin (5 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

Others remember that Lester was regularly teased and bullied in school. Some of this may have been attributable to “The Minnelli Gallery” of twitches, facial tics, and lip pursings—nervous habits that would become more pronounced over time—though the taunting young Lester received in school probably had more to do with his effeminacy than anything else. “He was quite flamboyant,” says Delaware historian Brent Carson. “He was very theatrical acting at times—even when he wasn’t acting. I think that during his early years, he was probably made fun of.”

25

Lester’s preference for playacting and drawing over fishing and football also led neighbors to make certain assumptions.

25

Lester’s preference for playacting and drawing over fishing and football also led neighbors to make certain assumptions.

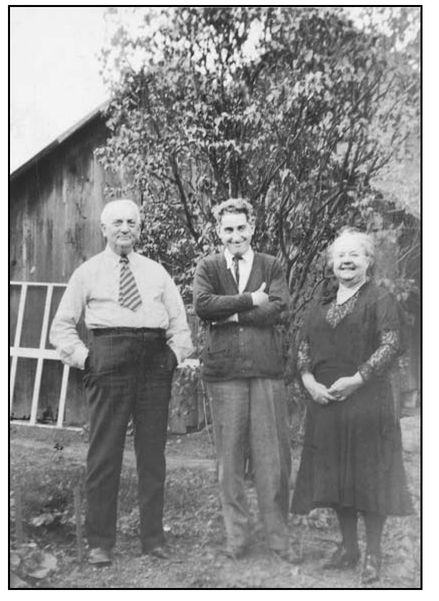

The Minnellis: V.C., Paul, and Mina at home on London Road in Delaware, Ohio. Lester had already moved on to the bright lights of Broadway. PHOTO COURTESY OF BARBARA BUTLER (PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN)

“I think he was gay,” says Delaware native Virginia Barber, whose father, Robert Stimmel, was a childhood friend of Lester Minnelli’s. “Of course, in those days, people never mentioned anything about that. You just didn’t back then. There were two words I never heard growing up here. One of them was ‘gay’ and the other one was ‘Jew.’”

26

26

The Minnellis’ Catholicism, Paul’s disabilities, Uncle Frank’s flamboyance, Lester’s effeminacy, and the fact that the Minnellis were “theater people”—all of this resulted in an alienating effect in the small-town confines of Delaware, Ohio. True, the Minnellis were well liked within the community, even admired, but just the same they would forever be viewed as somehow apart. Lester especially would feel the full impact of being branded “different.”

As the adolescent Lester was considered reserved and sensitive, it is curious that the editors of his high school yearbook would honor him with an epithet like “From the crown of his head to the soul of his foot, he is all mirth.”

27

Though, as Minnelli noted years later, “My timidity began to leave me during that last year at Willis High School.” Surrounded by students from

what he would later describe as “Delaware’s middle class,” Lester finally loosened up.

28

Minnelli’s thoughts on the latest Adolphe Menjou picture or his references to Modigliani were no longer met with blank stares. His jokes—no matter how Noel Coward-ish in tone—landed. The year at Willis seemed to fly by, with Lester stopping the show as the malevolent “Dick Deadeye” in the Boys’ and Girls’ Glee Club production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s

H.M.S. Pinafore

.

27

Though, as Minnelli noted years later, “My timidity began to leave me during that last year at Willis High School.” Surrounded by students from

what he would later describe as “Delaware’s middle class,” Lester finally loosened up.

28

Minnelli’s thoughts on the latest Adolphe Menjou picture or his references to Modigliani were no longer met with blank stares. His jokes—no matter how Noel Coward-ish in tone—landed. The year at Willis seemed to fly by, with Lester stopping the show as the malevolent “Dick Deadeye” in the Boys’ and Girls’ Glee Club production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s

H.M.S. Pinafore

.

Lester Minnelli steals the show as the malevolent “Deadeye Dick” in the Glee Club’s production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s

H.M.S. Pinafore

. PHOTO COURTESY OF BRENT CARSON (PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN)

H.M.S. Pinafore

. PHOTO COURTESY OF BRENT CARSON (PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN)

Just as Lester was beginning to blossom, graduation day arrived. As Minnelli received his diploma, it was with the knowledge that many of his friends would be heading off to Ohio Wesleyan in the fall. Lester would not be among the incoming freshmen. “I don’t know what I would have studied in college but the idea of going was ingrained in me,” Minnelli remembered. “I saw all the kids in high school were going and I was very disappointed that I didn’t have the money to go to college.”

29

The modest income that V.C. and Mina earned from teaching dance to Delaware’s aspiring Isadoras was enough to keep the family afloat but not to send Lester off to campus.

29

The modest income that V.C. and Mina earned from teaching dance to Delaware’s aspiring Isadoras was enough to keep the family afloat but not to send Lester off to campus.

In August 1921, only months after Lester received his high school diploma, a family tragedy would further taint what should have been a carefree

period for the recent graduate. As the

Delaware Daily Journal Herald

reported: “Mr. Frank P. Minnelli, aged 51 years, one of the best known theatrical men in Ohio, took his own life by firing two 32 caliber revolver bullets through his body as he stood in the Pennsylvania Railroad yards.” Frank left behind a letter addressed to his wife and brother that read: “Untold suffering has justified my act, good-bye.”

30

period for the recent graduate. As the

Delaware Daily Journal Herald

reported: “Mr. Frank P. Minnelli, aged 51 years, one of the best known theatrical men in Ohio, took his own life by firing two 32 caliber revolver bullets through his body as he stood in the Pennsylvania Railroad yards.” Frank left behind a letter addressed to his wife and brother that read: “Untold suffering has justified my act, good-bye.”

30

It was a heartbreaking end for Lester’s adored Uncle Frank, whom the

Delaware Journal

reported had been “mentally unbalanced by illness.” The papers attributed Frank Minnelli’s severe depression to a year-long battle with “dropsy and heart trouble.” Though at least one friend of the family was more matter of fact: “As for Frank, he hit the skids,” recalled Dorothy Eveland. “He became a drunkard and a penniless bum. His body was found one morning in a Delaware railroad yard. A very sad end.”

31

Though it was devastating to Lester, Uncle Frank’s suicide may have also provided his nephew with the motivation he needed to launch himself.

Delaware Journal

reported had been “mentally unbalanced by illness.” The papers attributed Frank Minnelli’s severe depression to a year-long battle with “dropsy and heart trouble.” Though at least one friend of the family was more matter of fact: “As for Frank, he hit the skids,” recalled Dorothy Eveland. “He became a drunkard and a penniless bum. His body was found one morning in a Delaware railroad yard. A very sad end.”

31

Though it was devastating to Lester, Uncle Frank’s suicide may have also provided his nephew with the motivation he needed to launch himself.

After Minnelli became famous, newspaper profiles would suggest that it was around this time that Lester “secretly planned a campaign” to leave Delaware and pursue his artistic ambitions in the big city. New York was his first choice, but he’d settle for Chicago if necessary. Of course, the big move required money. “I think the first job he ever had in Delaware, my father gave him,” says Barbara Butler. “My father owned a confectionary and Lester was hired to work there. As the story goes, Lester was carrying this tray up the stairs one day and he dropped it and everything spilled all over. My father was unhappy with him and fired him. Mrs. Minnelli asked if my father would take him back as they were in very poor circumstances at that time. So, Lester came back for awhile.”

32

One job lead to another. He worked in an angler’s shop, painting artificial fishing flies. He created the advertising curtain for the local movie house. Finally, he had saved up enough to put his “secret campaign” into action.

32

One job lead to another. He worked in an angler’s shop, painting artificial fishing flies. He created the advertising curtain for the local movie house. Finally, he had saved up enough to put his “secret campaign” into action.

2

Window Dressing the World

MINNELLI SAID GOODBYE to Delaware and, true to his word, never looked back.

g

It was on to Chicago—and in the midst of the Roaring ’20s, no less. That “toddling town” was teeming with activity, anarchists, and bathtub gin. Al Capone was at large. The

Daily Tribune

headlines blared all the latest: “$22,000 to Fight Booze,” “To Uphold Law in Scopes Trial, Prayers Go On,” “Bandits Bind Miss Bingham, Steal $1,500.” Amid Chicago’s speakeasies, nightclubs, bookie joints, and brothels, Minnelli absorbed what he described as the city’s “raucous vitality.”

1

It was certainly a far cry from the well-mannered tranquility of Delaware, Ohio.

g

It was on to Chicago—and in the midst of the Roaring ’20s, no less. That “toddling town” was teeming with activity, anarchists, and bathtub gin. Al Capone was at large. The

Daily Tribune

headlines blared all the latest: “$22,000 to Fight Booze,” “To Uphold Law in Scopes Trial, Prayers Go On,” “Bandits Bind Miss Bingham, Steal $1,500.” Amid Chicago’s speakeasies, nightclubs, bookie joints, and brothels, Minnelli absorbed what he described as the city’s “raucous vitality.”

1

It was certainly a far cry from the well-mannered tranquility of Delaware, Ohio.

Fortunately, Lester wasn’t alone in the big city. Upon his arrival, he moved in with his Grandmother Le Beau (Mina’s mother) and his Aunt Amy,

h

a former trapeze artist who had toured on the vaudeville circuit. Their modest house at 1220 West Polk Street was near Notre Dame de Chicago, where Grandmother Le Beau and Aunt Amy would faithfully attend early Mass and listen to the sermons offered by the Fathers of the Blessed Sacrament. But not Lester, who by this time admitted “falling out” as a practicing Catholic. His mind was on more worldly matters—namely finding a job.

h

a former trapeze artist who had toured on the vaudeville circuit. Their modest house at 1220 West Polk Street was near Notre Dame de Chicago, where Grandmother Le Beau and Aunt Amy would faithfully attend early Mass and listen to the sermons offered by the Fathers of the Blessed Sacrament. But not Lester, who by this time admitted “falling out” as a practicing Catholic. His mind was on more worldly matters—namely finding a job.

With his artist’s portfolio tucked under his arm, Lester embarked on a job search, which abruptly ended when he was “seduced” by a spectacular

Florentine-style window display at Marshall Field. After inquiring about employment opportunities at the store, Lester was led to the top floor office and introduced to one Arthur Valair Fraser,

i

Marshall Field’s display director. An innovative force in the world of window display, Fraser had combined papier-mâché and wax figures to create what would ultimately evolve into the department-store mannequin. After examining Lester’s watercolors, “The King of Display” (as Fraser was known) hired him on the spot. With one fortuitous visit, Minnelli had gone from the ranks of the unemployed to Mr. Fraser’s fourth apprentice. It was the best kind of window shopping.

Florentine-style window display at Marshall Field. After inquiring about employment opportunities at the store, Lester was led to the top floor office and introduced to one Arthur Valair Fraser,

i

Marshall Field’s display director. An innovative force in the world of window display, Fraser had combined papier-mâché and wax figures to create what would ultimately evolve into the department-store mannequin. After examining Lester’s watercolors, “The King of Display” (as Fraser was known) hired him on the spot. With one fortuitous visit, Minnelli had gone from the ranks of the unemployed to Mr. Fraser’s fourth apprentice. It was the best kind of window shopping.

Lester and his fellow trimmers had their work cut out for them. As the Midwest’s largest department store, Marshall Field featured sixty-seven windows in need of dressing. The store’s meticulously designed window displays were unequaled and the envy of other retailers. Although Lester was disappointed that his new position didn’t allow him to be as creative as he’d hoped, it was at Marshall Field that “the Minnelli Touch” was born. The future director would discover which combination of colors pleased the eye, how the trappings surrounding a subject were just as important as the subject itself, and that even the smallest details enhanced the big picture. As Minnelli would later strive “to bring the sleek lines of modernism into the theater,” he hoped to take Marshall Field’s “excellent windows into the twentieth century.”

2

But for the moment, Lester’s greatest challenge involved deciding which tie went best with which display model suit.

2

But for the moment, Lester’s greatest challenge involved deciding which tie went best with which display model suit.

Fifty years after working at Marshall Field, Minnelli would write about the experience in the telegraphic notes for his autobiography. “Don’t think anyone gay in the window dressing department,” he mused. In the published version of his memoir, he assured readers that his fellow display men “were all married and raising families.”

3

While this may be true, Minnelli seemed eager to distance himself from anything that smacked of the homoerotic, including the traditionally gay milieu of window dressing. Perhaps the need to publicly distance himself had something to do with the fact that during his years in Chicago, Minnelli almost certainly embarked on a relationship with another man—one named Lester Gaba.

3

While this may be true, Minnelli seemed eager to distance himself from anything that smacked of the homoerotic, including the traditionally gay milieu of window dressing. Perhaps the need to publicly distance himself had something to do with the fact that during his years in Chicago, Minnelli almost certainly embarked on a relationship with another man—one named Lester Gaba.

“Lester always maintained that he had some kind of dalliance or liaison with Minnelli,” says designer Morton Myles, who knew Lester Gaba when both resided on Fire Island. “I can’t say yes or no for certain, but he always alluded to the fact that they had an affair. . . . It may have started as a trick

and then turned into a friendship. Anything is possible. But on the other hand, Lester was known to embroider quite a bit. I mean, there wasn’t a New York City taxi driver that he didn’t have when he was short on change for the fare.”

4

and then turned into a friendship. Anything is possible. But on the other hand, Lester was known to embroider quite a bit. I mean, there wasn’t a New York City taxi driver that he didn’t have when he was short on change for the fare.”

4

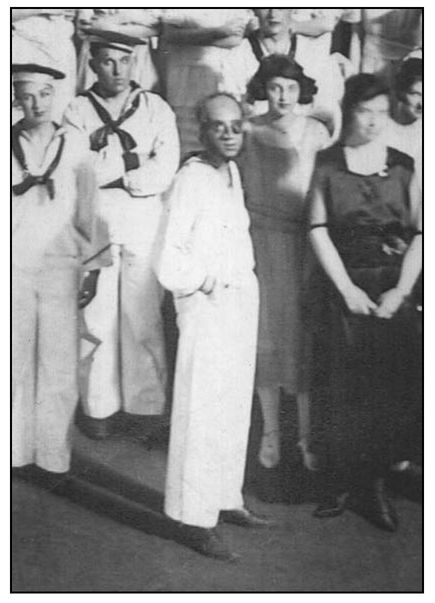

Lester Gaba’s Hannibal High School yearbook photo from 1924 (when he was still known as “Abe”). “Lester always maintained that he had some kind of dalliance or liaison with Minnelli,” says designer Morton Myles, who befriended Gaba in his later years. PHOTO COURTESY OF STEVE CHOU

While it’s been said that opposites attract, Minnelli and Gaba could not have been more similar. There was the uncanny coincidence of their first names (though Gaba’s real first name was “Abe,” and it’s unclear when he started calling himself “Lester”). In terms of their physical appearance, there was more than a passing resemblance between the two. Like Minnelli, Gaba was from middle America (Hannibal, Missouri), and he, too, had left his hometown while still a teenager. Landing in Chicago, Gaba worked at Marshall Field as an errand boy, though the two Lesters most likely met when both were working for Balaban and Katz, where Minnelli designed costumes and Gaba designed promotional posters.

Gaba had the same need to express himself visually that Minnelli did. Both were constantly window dressing the world and transforming the everyday into something far more enchanting. As Gaba recalled, “As soon as I was old enough to make a crepe paper rose, I began to help my father trim the windows of his clothing store in Hannibal. And it’s probably the best experience I ever had.”

5

Gaba could sketch almost as well as Minnelli, but it was his whimsical soap sculptures—southern belles and white knights carved out of ordinary bars of Ivory that won him the most attention. A decade after their friendship—or affair, as the case may be—blossomed in Chicago, Minnelli and Gaba would resume their relationship in New York. Through it all, Minnelli remained devoted to his one true love—his career.

Lester Gaba told

Esquire

’s Hugh Troy that he had “never met a creative person whose mind is so inseparable from his work, and who is so willing to sacrifice everything—amusement, friends, and self—to achieve his ambitions as is Minnelli.”

6

5

Gaba could sketch almost as well as Minnelli, but it was his whimsical soap sculptures—southern belles and white knights carved out of ordinary bars of Ivory that won him the most attention. A decade after their friendship—or affair, as the case may be—blossomed in Chicago, Minnelli and Gaba would resume their relationship in New York. Through it all, Minnelli remained devoted to his one true love—his career.

Lester Gaba told

Esquire

’s Hugh Troy that he had “never met a creative person whose mind is so inseparable from his work, and who is so willing to sacrifice everything—amusement, friends, and self—to achieve his ambitions as is Minnelli.”

6

Other books

Bound to Be His (The Archer Family Book 2) by Allison Gatta

Devils Kiss by Zoe Archer

World of Echos by Kelly, Kate

Heroes for My Son by Brad Meltzer

Fencer by Viola Grace

Unto All Men by Caldwell, Taylor

Quiet Strength by Dungy, Tony, Whitaker, Nathan

Enter a Murderer by Ngaio Marsh

Picture This by Norah McClintock