Mark Griffin (7 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

One of Vincente’s earliest champions was an indefatigable young woman named Eleanor Lambert. Although not yet the extraordinarily influential force in the fashion world that she would later become, Lambert had already developed an unerring eye for spotting legitimate talent. She immediately recognized something unique and unusually beautiful about Minnelli’s ever-expanding portfolio.

“She was kind of a talent spotter,” says Lambert’s son William Berkson:

I witnessed this probably all of my life with her. . . . People would come to her office or they would come at tea time. Somebody’s always got . . .

something

. In the later days it would be a guy with a new line of bridal outfits. In the old days, it was the latest designer. The enthusiasm and the energy she had went beyond business. In other words, a lot of what she was offering was just free advice. She really just seemed to delight in finding the next big thing. . . . So, a lot of what she did was basically say, “Sit right here. You better get to know me because I can see that you’re a comer and I can clue you in.”

6

something

. In the later days it would be a guy with a new line of bridal outfits. In the old days, it was the latest designer. The enthusiasm and the energy she had went beyond business. In other words, a lot of what she was offering was just free advice. She really just seemed to delight in finding the next big thing. . . . So, a lot of what she did was basically say, “Sit right here. You better get to know me because I can see that you’re a comer and I can clue you in.”

6

Lambert saw to it that Minnelli met all the right people.

Another who was taken with Vincente’s artistic abilities was Joseph Monet, editor of the notorious Van Rees Press. Monet hired Minnelli to illustrate a new edition of the quasi-erotic

Casanova’s Memoirs

in a manner reminiscent of English surrealist Aubrey Beardsley. Vincente’s art nouveau- style drawings of androgynous figures engaged in boudoir shenanigans of every description made clear what the Venetian adventurer’s recollections only hinted at.

Casanova’s Memoirs

in a manner reminiscent of English surrealist Aubrey Beardsley. Vincente’s art nouveau- style drawings of androgynous figures engaged in boudoir shenanigans of every description made clear what the Venetian adventurer’s recollections only hinted at.

JUST AS HE HAD FOR DELAWARE’S movie house years earlier, Vincente would design the curtain for the ninth edition of Earl Carroll’s

Vanities

. Unlike the modest drape at The Strand, Carroll’s curtain, at 300 feet wide, was on the grandest of grand scales, and it would be on full view before a seen-it-all Broadway audience. The curtain would also serve as the centerpiece of Carroll’s gleaming new art deco theater. Inspired by the exquisite (and exquisitely expensive) curtains Erté had designed for the Folies-Bergère, Vincente was determined to achieve a similarly stunning effect—though at a fraction of the cost. Rising to the challenge, Minnelli devised a visual stunner: a “living” curtain in absinthe green chiffon with silver embroidery that featured “strategically placed openings” in the fabric through which Carroll’s comely showgirls could insert arms, legs, or other parts of their anatomies: Peek-a-boo. The effect was dazzling.

Vanities

. Unlike the modest drape at The Strand, Carroll’s curtain, at 300 feet wide, was on the grandest of grand scales, and it would be on full view before a seen-it-all Broadway audience. The curtain would also serve as the centerpiece of Carroll’s gleaming new art deco theater. Inspired by the exquisite (and exquisitely expensive) curtains Erté had designed for the Folies-Bergère, Vincente was determined to achieve a similarly stunning effect—though at a fraction of the cost. Rising to the challenge, Minnelli devised a visual stunner: a “living” curtain in absinthe green chiffon with silver embroidery that featured “strategically placed openings” in the fabric through which Carroll’s comely showgirls could insert arms, legs, or other parts of their anatomies: Peek-a-boo. The effect was dazzling.

Although critic Robert Benchley would dismiss “the definitely Negroid sense of color,” the theatrical community was abuzz over Minnelli’s audacious opulence. Vincente’s ability to produce sumptuous, eye-catching effects on a very thin dime had not been lost on budget-conscious Earl Carroll. The impresario promoted Minnelli to scenic and costumer designer for the 1932 installment of the

Vanities

.

Vanities

.

Carroll would also be responsible for Minnelli’s first appearance on film. In a 1933 promotional short entitled

Costuming the Vanities

, Carroll and his bashful costume designer are seen reviewing wardrobe sketches for star Beryl

Wallace (who would later become the showman’s wife). While Carroll looks directly at the camera, Minnelli does everything to avoid it. His shyness is palpable. It appeared that there was more than a little bit of Lester left in suave sophisticate Vincente Minnelli after all.

Costuming the Vanities

, Carroll and his bashful costume designer are seen reviewing wardrobe sketches for star Beryl

Wallace (who would later become the showman’s wife). While Carroll looks directly at the camera, Minnelli does everything to avoid it. His shyness is palpable. It appeared that there was more than a little bit of Lester left in suave sophisticate Vincente Minnelli after all.

While the

Vanities

was still on the boards, Vincente was summoned to assist glamorous Grace Moore, the first in a glittering line of great lady stars in his life. “The Tennessee Nightingale” (as Moore was nicknamed) had triumphed in the Metropolitan Opera’s production of

La Bohème

four years earlier. Now Karl Millocker’s comic operetta,

The DuBarry

, was being prepared for Moore and she had personally requested twenty-nine-year-old Minnelli as the art director, hopeful that he could do for her what he had done for Earl Carroll and his curtain. Similar to the type of exacting star Vincente would encounter some forty years later when he worked with Barbra Streisand, Moore was legitimately talented, equipped with a mercurial temperament, and had very “definite ideas about what was seemly for her,” Minnelli recalled decades after their uneasy collaboration.

7

Vanities

was still on the boards, Vincente was summoned to assist glamorous Grace Moore, the first in a glittering line of great lady stars in his life. “The Tennessee Nightingale” (as Moore was nicknamed) had triumphed in the Metropolitan Opera’s production of

La Bohème

four years earlier. Now Karl Millocker’s comic operetta,

The DuBarry

, was being prepared for Moore and she had personally requested twenty-nine-year-old Minnelli as the art director, hopeful that he could do for her what he had done for Earl Carroll and his curtain. Similar to the type of exacting star Vincente would encounter some forty years later when he worked with Barbra Streisand, Moore was legitimately talented, equipped with a mercurial temperament, and had very “definite ideas about what was seemly for her,” Minnelli recalled decades after their uneasy collaboration.

7

Moore’s ideas about the way she should be presented on stage clashed with many of Minnelli’s most inventive concepts. When Vincente proposed that Moore wear a brief kimono-style drape in a brothel sequence, the star huffed and stormed out. Moore’s coach ride to the palace of Louis XV had been imaginatively conceived by Minnelli so that that the audience could glimpse the rear of the coach and its rotating wheel through the carriage’s back window, but when Minnelli suggested that stagehands rock the coach back and forth to complete the illusion, Moore complained that she was queasy and nixed the idea. To make matters worse, the notoriously absent-minded Minnelli sent the leading lady a congratulatory telegram on opening night—only it was addressed to popular singer

Florence

Moore. The star was not amused, and she was probably even less so when she read Brooks Atkinson’s review of

The DuBarry

, which began by praising Minnelli’s “richness of color and sweep of line” before getting around to her performance.

Florence

Moore. The star was not amused, and she was probably even less so when she read Brooks Atkinson’s review of

The DuBarry

, which began by praising Minnelli’s “richness of color and sweep of line” before getting around to her performance.

Having established himself as one of the most visually inventive talents on Broadway, Minnelli was made a set designer by his bosses at Paramount. Not long after the promotion, Paramount shifted its stage-show operations to Astoria, Long Island, where the East Coast division of Paramount Pictures was headquartered. No sooner had Minnelli been promoted than Paramount decided to drop its costly stage shows in favor of big band appearances.

The career-driven workhorse was suddenly out of a job. Though, as it turned out, not for very long. After spending only a couple of months among the ranks of the unemployed, Vincente received a call from the newly opened

Radio City Music Hall. Was he interested in a position as the Music Hall’s chief costume designer? The offer couldn’t have come at a better time for Minnelli. And without question, “The Showplace of the Nation” needed all the help it could get.

Radio City Music Hall. Was he interested in a position as the Music Hall’s chief costume designer? The offer couldn’t have come at a better time for Minnelli. And without question, “The Showplace of the Nation” needed all the help it could get.

On December 27, 1932, when Radio City had opened its doors, the response from the press and public alike had been positively underwhelming. Rather than presenting a bold, modern attraction to complement the Music Hall’s gleaming art deco design, the inaugural production staged by Robert Edmond Jones proved to be a fustily old-fashioned affair—a virtual funeral rite for vaudeville, complete with Fraulein Vera Schwarz and the Flying Wallendas. A catastrophe in nineteen acts, the entire performance had been conceived and supervised by Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel, Radio City’s director general. The day after the disastrous opening, Brooks Atkinson took Rothafel to task in the

New York Times

: “The truth seems to be that maestro Roxy, the celebrated entrepreneur of Radio City, has opened his caravansary with an entertainment, which on the whole, does not provoke much enthusiasm.”

8

New York Times

: “The truth seems to be that maestro Roxy, the celebrated entrepreneur of Radio City, has opened his caravansary with an entertainment, which on the whole, does not provoke much enthusiasm.”

8

It was resoundingly clear to the management that something drastic had to be done before Radio City went under quicker than the

Lusitania

. While the Music Hall’s theaters were temporarily closed, no end of changes took place. Robert Edmond Jones resigned, as did costume designer James Reynolds. Emergency meetings were called. Roxy and company would need to chart an entirely new course.

Lusitania

. While the Music Hall’s theaters were temporarily closed, no end of changes took place. Robert Edmond Jones resigned, as did costume designer James Reynolds. Emergency meetings were called. Roxy and company would need to chart an entirely new course.

A mix of movies and live stage spectacles had proven to be a winning combination for Minnelli’s former employer, Balaban and Katz. Other theater chains had found success with this varied approach as well. So it came as no surprise when Radio City announced that it was adopting the stage and screen format. When it reopened on January 11, 1933, Radio City’s revamped program included a feature film (Frank Capra’s

The Bitter Tea of General Yen

) and a considerably shortened stage show. This would prove to be a winning formula. “From January 1933 until it closed as a movie house, Radio City Music Hall invariably, inflexibly, and with no exception, always changed its show on Thursday,” says historian Miles Krueger. “Every single week there were new sets, new costumes, new ballets, new choral numbers. They had a men’s chorus and visiting comedians and acrobats and God knows what. Everything for about 35 cents. That’s how they could fill 7,000 seats.”

9

The Bitter Tea of General Yen

) and a considerably shortened stage show. This would prove to be a winning formula. “From January 1933 until it closed as a movie house, Radio City Music Hall invariably, inflexibly, and with no exception, always changed its show on Thursday,” says historian Miles Krueger. “Every single week there were new sets, new costumes, new ballets, new choral numbers. They had a men’s chorus and visiting comedians and acrobats and God knows what. Everything for about 35 cents. That’s how they could fill 7,000 seats.”

9

While the Music Hall’s format was being overhauled, Radio City’s management decided that an entirely new production staff was needed to breathe some life into what was supposed to be the “live” portion of the bill. Someone

remembered Minnelli’s striking contributions to the Earl Carroll extravaganzas, and by February 1933 Vincente was in place as Radio City’s chief costume designer.

remembered Minnelli’s striking contributions to the Earl Carroll extravaganzas, and by February 1933 Vincente was in place as Radio City’s chief costume designer.

Minnelli would be working closely with Roxy Rothafel, a former marine drill sergeant. As Vincente would soon discover, dealing with Roxy was a major occupational hazard. Like virtually everyone under Rothafel’s command, Minnelli found the irascible impresario “obstreperous and fault-finding.”

10

This was certainly the case with art director Clark Robinson, who threw in the towel after yet another heated exchange with the impossible-to-please Rothafel. In terms of finding an immediate replacement for Robinson, Roxy didn’t have to look too far.

10

This was certainly the case with art director Clark Robinson, who threw in the towel after yet another heated exchange with the impossible-to-please Rothafel. In terms of finding an immediate replacement for Robinson, Roxy didn’t have to look too far.

Although he was still as wet as the Music Hall’s walls, Minnelli was now Radio City’s new art director—this in addition to his already overwhelming costuming duties. It was a head-swelling double dose of responsibility—though almost immediately, Vincente would find himself cut down to size. Roxy, an equal opportunity put-down artist, would make the mild-mannered, soft-spoken Minnelli his whipping boy of choice. As Vincente recalled, “Instead of doing the job of three men, I would now be doing the job of six . . . and getting a proportionally larger share of Roxy’s sarcasms.”

11

11

In July 1933, Minnelli was handed his first assignment as art director, and it would call upon every ounce of his artistic ingenuity to fill the role. Vincente’s training under Balaban and Katz would prove invaluable as he conjured up such sumptuous set pieces as a “Water Lily” ballet, a Cuban-themed sketch (complete with a pair of mammoth fighting cocks), and a Parisian dress boutique in which the shapely “Roxyettes” would strut their stuff—all of it crammed into fifty minutes. Within a matter of days, Minnelli would be expected to whip up another batch of equally imaginative settings and a dazzling array of costumes. It was Vincente’s designs for December’s “Scheherzade Suite” (complete with Persian rugs and elephants) that made both the

New York Times

and Roxy take notice. “You know, I’ve been picking on this fellow,” Rothafel admitted to his beleaguered staff. “All that picking brought fine results. . . . He’s an artist.”

12

New York Times

and Roxy take notice. “You know, I’ve been picking on this fellow,” Rothafel admitted to his beleaguered staff. “All that picking brought fine results. . . . He’s an artist.”

12

No sooner had his commanding officer tossed Minnelli a bit of long-overdue praise than Rothafel was sent packing. The management had more than likely received one too many complaints regarding Roxy’s take-no-prisoners tactics. Although the ulcer-inducing confrontations with Roxy were over, the nonstop work and continual sleep deprivation were still very much a part of Vincente’s exhaustively paced existence. He fought off fatigue with gallons of black coffee. Racing to keep up with the grueling production schedule,

the hourly backstage dramas, and the constant demands of everyone around him, Minnelli had precious little time to claim as his own: “I’d stay up all night and light the new show, then we’d start planning the next one at lunch the following day.”

13

the hourly backstage dramas, and the constant demands of everyone around him, Minnelli had precious little time to claim as his own: “I’d stay up all night and light the new show, then we’d start planning the next one at lunch the following day.”

13

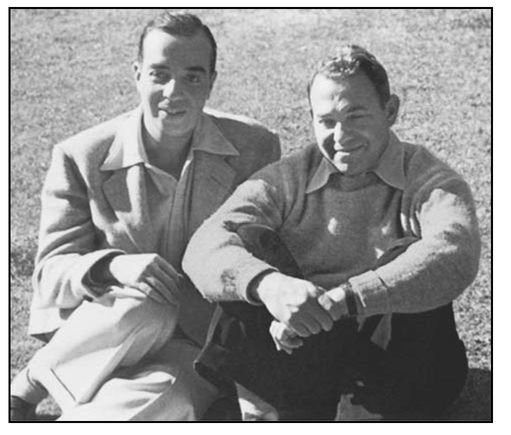

Vincente and composer E. Y. “Yip” Harburg in the ’30s. Minnelli said of his equally talented friend: “I was drawn to his rare good nature, and he must have seen in me a kid who needed more polish and dash.” PHOTO COURTESY OF LILY MELTZER AND THE HARBURG FOUNDATION

If he had been a self-declared “failure” at nine, Minnelli was single-mindedly determined to make up for his “misspent” youth. Virtually every minute of the day was consumed with getting a new show ready. When he wasn’t placating neurotic stars or fixated on some bit of visual minutia, Minnelli somehow found time to acquire a remarkable collection of friends—a veritable Who’s Who of the entertainment world.

Other books

The Sword of God - John Milton #5 (John Milton Thrillers) by Mark Dawson

Vengeance by Amy Miles

Las nieblas de Avalón by Marion Zimmer Bradley

Amber Morn by Brandilyn Collins

A Glint In Time (History and Time) by Frank J. Derfler

Into The Dark Flame (Book 4) by Martin Ash

Black Scar by Karyn Gerrard

Six Moon Dance by Sheri S. Tepper

The Lady and the Lawman by Jennifer Zane

Promises Reveal by McCarty, Sarah