Marmee & Louisa (51 page)

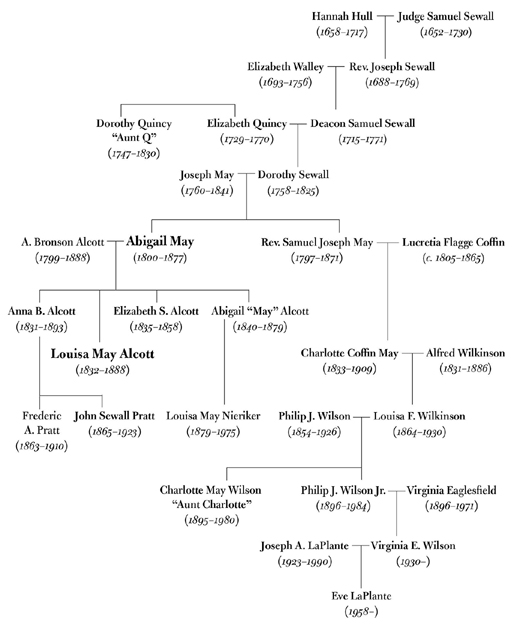

Authors: Eve LaPlante

A half-hour south of Quincy, in the town of Norwell, Massachusetts, formerly South Scituate, Samuel Joseph’s house and church are still standing. The house, a colonial at 841 Main Street known as the Elijah Curtis House or “May Elms” because of the trees planted by the minister, is privately owned. This is where Louisa and her sister spent several summers in the late 1830s. Less than a mile away, in the town center, is the First Church of Norwell, established in 1642 and looking much as it did in Samuel Joseph’s day. The church building was erected in 1830, a few years before his arrival, and contains a Paul Revere bell, a pipe organ by Ebenezer Goodrich, and an Aaron Willard clock (

www.firstparishnorwell.org

).

The town of Melrose, home to Samuel E. Sewall and his family, whom the Alcotts often visited and with whom Louisa boarded, is north of Boston on the Mystic River. In the 1860s Anna and John Pratt moved from urban Chelsea to rural Melrose. To get a sense of nineteenth-century Melrose, visit the Middlesex Fells Reservation, which has several ponds and more than a hundred miles of trails. At the nearby border of Stoneham is Spot Pond, which the Mays and Alcotts knew well. Samuel Joseph May recalled in his memoir an 1817 trip to Spot Pond for a canal party hosted by Daniel Webster, who had

just completed two terms in the United States House of Representatives. At the party the ladies asked the gentlemen to gather water lilies from the pond. “The more the probability of getting them seemed to recede,” Samuel Joseph observed, “the more earnest became the desires of the young ladies to be possessed of the beautiful flowers.” While the other young men left in search of a boat, the nineteen-year-old Harvard graduate, who was wearing his best suit, remained with Daniel Webster and the ladies, who began to glare at him. Urged on by Webster, Samuel Joseph waded into the pond to collect water lilies. “When I reached the shore, soaked from my waistcoat pockets downwards, and presented to each of the ladies one or more of the flowers they had so much desired, their thanks were to me quite as grateful as the fragrance of the lilies.” Despite Samuel Joseph’s “pleasant introduction to the great orator” in 1817, Webster’s later defense of slavery, his “fearful recreancy to the cause of liberty, impelled me to lift my voice on the 4th of July, 1838, in earnest condemnation of one whom I had once so profoundly respected.”

The hills and orchards of Walpole, New Hampshire, just over an hour’s drive northwest of Boston, are much as they were in the 1850s, when Louisa and Abigail lived there. Heading east into Maine, you can still visit the 1797 Lake House in Waterford that housed the water-cure establishment where Abigail worked and lived in 1848. In the early twenty-first century the Lake House, at 686 Waterford Road, still operated as an inn in the historic district of this village in the foothills of the White and Mahoosuc mountains. Waterford, a vacation community for nearly two hundred years, is as lovely now as it must have been in the Alcotts’ day. The remains of the tubs in which patrons of the spa soaked are said to be visible below the annex of the inn, across the lawn to the right. The farmhouse that belonged to Abigail’s friend Ann Gage, whom Abigail often visited, is up the hill to the right of the inn, still occupied by Gage’s descendants. Across the road from the inn are paths to nearby Keoka Lake.

In southern New England, Samuel Joseph’s first church still stands in Brooklyn, Connecticut, near the Rhode Island border. A few miles south of Brooklyn on Route 169, at the Route 14 intersection, is Prudence Crandall’s Canterbury house, the site of New England’s first school for black girls. The house, now a museum and National Historic Landmark on Connecticut’s Freedom Trail and Women’s Heritage Trail, is open to the public Wednesdays through Sundays (860-546-9916). Each fall the

Prudence Crandall Museum hosts a “Tea with Prudence and Sarah” in which actors playing the teacher and her first black student, Sarah Harris, reenact the events of 1833 and 1834. A statue of Prudence Crandall, who at the end of the twentieth century was named Connecticut’s state heroine, adorns the state Capitol, in Hartford.

Louisa enjoyed visits to New York City in the last decade of her life, when she was a media celebrity. In 1885, for example, she lived for a while at 41 West 26th Street. Her Goddard and Sewall cousins resided on 77th Street on the Upper East Side, and her cousin Charlotte May Wilkinson spent her final years with several of her grown children in an apartment at 129 East 76th Street.

Louisa’s birthplace of Germantown is seven miles northwest of central Philadelphia. Germantown, a separate town from Philadelphia until 1854, was then a summer retreat for wealthy Philadelphians. The many extant historic houses along Germantown’s cobbled streets include that of Reuben Haines, the Quaker who invited Bronson here in 1830. The Wyck house, as it is known, at the corner of Germantown Avenue and East Walnut Lane, is open to the public several days a week from April to December (

www.Wyck.org

). Louisa and her sister Anna as toddlers visited Wyck house with their mother and likely played in its rose garden. While some historians assert that Louisa returned to the house in 1876 while in Philadelphia for the installation of her cousin the Reverend Joseph May at the city’s First Unitarian Church, at Chestnut Street, Louisa herself wrote to a friend in 1881 of “my birth-place, which I have never visited since I left it at the mature age of two.”

Pine Place, the Germantown alley on which the Alcotts were living when Louisa was born, and their rented stone cottage surrounded by pine trees are long gone. Nevertheless, a historic sign marks the spot, at 5424 Germantown Avenue, which is now occupied by a piano factory. Around the corner, at 5501 Germantown Avenue in the old Market Square, the Germantown Historical Society has exhibits and information about the Alcotts and many local historic sites (

www.germantownhistory.org

). Germantown is a major stop on the African American Heritage Guide to Philadelphia’s Historic Northwest (

www.FreedomsBackyard.com

).

The Union Hotel Hospital (later Georgetown General and Union Hospital), in which Louisa worked as a nurse, was torn down in the 1930s and replaced by a gas station. A SunTrust Bank office now sits on the site,

at the northeast corner of M (then Bridge) Street and 30th Street NW (then Washington) in Georgetown. This part of M Street is now a thriving shopping district around Market House, Georgetown’s market since 1751.

During the Civil War America’s capital was filled with hospitals and wounded soldiers and surrounded by forts. Georgetown was a busy port, its population nearly a third African-American, some enslaved and some free. Louisa liked to walk up into the Georgetown hills and down to the nearby Chesapeake & Ohio canal to watch mules draw barges. The C&O canal was intended to connect to the Ohio River, but the rapid development of railroads made this method of transportation obsolete. A canal lock can still be seen on Jefferson Street, between M and K streets. On her walks Louisa would have passed the Old Stone House, built in 1765 on the same side of M Street as the hospital, and now considered the oldest standing building in Washington, D.C. Operated by the National Park Service and open to the public, the Old Stone House is part of the vast Rock Creek Park that runs north from Georgetown along the Rock Creek to the district’s topmost corner (

www.nps.gov/rocr

).

Louisa knew canals well from her frequent visits to Syracuse, New York, the city in the Finger Lakes region where her uncle’s family lived after 1844. Portions of the Erie Canal are still visible beneath Syracuse’s Canal Street and Erie Boulevard. In the nineteenth century Syracuse was known as “that laboratory of abolitionism, libel, and treason” and “the great central depot” on the Freedom Trail. Residents of nearby towns included Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Harriet Tubman, Matilda Joslyn Gage, and Gerrit Smith. The Fugitive Slave Law Convention in 1850 occurred in nearby Cazenovia. In Seneca Falls, where the first women’s rights convention was held in 1848, the visitor center of the Women’s Rights National Historical Park is open daily year round (

www.cnyhistory.org

).

Neither the May house nor Samuel Joseph’s church here are standing, and it is difficult to see the bones of nineteenth-century Syracuse in the modern city. The Onondaga Historical Association Museum and Research Center offers exhibits and collections on Syracuse history, the Jerry Rescue, Samuel Joseph May, abolition, and women’s rights. The society holds personal papers of Samuel Joseph May and Colonel Joseph May, although the bulk of Samuel Joseph May’s extant papers are about

90 minutes to the north in the archives of the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections of the Cornell University Library, where his painting of Prudence Crandall still hangs.

Louisa and Abigail often visited the Mays at their spacious home at 157 James Street, then a broad residential road less than a mile northeast of the center of Syracuse. James Street is now commercial, most of its mansions burned or razed. An apartment building occupies the site of the May house at what is now 472 James Street.

Samuel Joseph’s Church of the Messiah was in the center of the city one block north of the Erie Canal at the corner of Burnet and Lock (now State) streets. The site is now a parking lot beside the elevated Interstate 690. In the mid twentieth century Samuel Joseph’s former congregation moved to eastern Syracuse where it continues today as the May Memorial Unitarian Universalist Society, at 3800 East Genesee Street (315-446-8920 or

www.mmuus.org

). Its May Memorial Room contains several of Samuel Joseph’s bibles, a two-volume Bible that his wife received from Colonel May’s second wife in 1834, a bust and photographs of the minister, and some of his journals. Outside and to the right of the church is a large marble plaque in honor of Samuel Joseph that overlooks the May Memorial garden and a brook.

My final stop in Syracuse was the Oakwood Cemetery, adjacent to the campus of Syracuse University, at 940 Comstock Avenue. No one was present at the cemetery office when I visited, so it took me nearly an hour to find the Mays’ graves. (I recommend calling 315-475-2194 for directions and then entering the cemetery from Colvin Avenue.) Down a winding, rutted road near the back of the cemetery, perched atop a lovely knoll, is a huge, ornate monument to the Wilkinson family. Arrayed beneath this sculpture and below many Wilkinsons are the graves of Samuel Joseph (“Born in Boston Sept. 12, 1797, Died in Syracuse July 1, 1871”) and his wife (“Lucretia Coffin, Wife of Samuel Joseph May, Born in Portsmouth, NH, Died in Syracuse May 8 1865”), several of their children, their daughter Charlotte’s sons and daughters (including Abigail’s namesake Abby May Wilkinson, who died at age two), and, beneath a small granite slab surrounded by grass, my aunt “Charlotte May Wilson, 1895–1980.”

Acknowledgments

I

am most grateful to Lisa Stepanski, author of

The Home Schooling of Louisa May Alcott

, to Lis Adams, director of education at Orchard House, and to Rose LaPlante for their assistance in transcribing family papers and archival documents. Lisa Stepanski and Lis Adams also read the manuscript, made editorial suggestions, and guided me to important materials. Cynthia Barton, author of

Transcendental Wife

, shared her research notes and answered all my questions. Catherine Rivard provided several years of expert advice on the Alcott and May families. Megan Marshall, author of

The Peabody Sisters

, generously provided several of Elizabeth Peabody’s letters that I might have overlooked. Virginia LaPlante, Liza Hirsch, and Alison McGandy read the manuscript and made invaluable suggestions. Jan Turnquist allowed me to roam the rooms and collections of Orchard House, of which she is executive director. The historian and curator Edward Furgol, D. Phil., continued to offer sage counsel. Alcott and May scholars whose work I relied on in addition to Cynthia Barton and Lisa Stepanski include Elizabeth Lennox Keyser, Joel Myerson, Daniel Shealy, Sarah Elbert, John Matteson, Madeleine Stern, Donald Yacovone, Madelon Bedell, and Ted Dahlstrand. I wish to thank Maria Powers of Orchard House for her help with images and permissions.