Mayday Over Wichita (12 page)

Read Mayday Over Wichita Online

Authors: D. W. Carter

T

HE

V

EIL

R

EMOVED

Despite the amazing efforts of the community, local agencies and the air force, the issue of race could not be avoided for long. Relief workers were mostly white; the victims, mostly black. The Red Cross had no black board members (one, Jim Garmon, was recruited after the crash), and few blacks, if any, worked for relief agencies in Wichita. All Wichita banks set up disaster accounts in order to take in donations to help repair homes and relocate residents, but these efforts were never intended to override the housing restrictions that kept blacks out of white neighborhoods (though some hoped they would).

210

The Red Cross did not wish to become entangled in the equal housing issuesâso instead, it gained approval to allot ninety dollars a month in cash payments for rent to those still needing shelter. Rumors quickly spread that the majority of the houses offered were in the ghetto, and others were simply uninhabitable. In an interview conducted by two Wichita high school teachers, Leonard Wesley and Frank Carpenter, on April 20, 1965, they spoke to residents about the generous offer from some property owners in Wichita to supply homes to those in need. Among those interviewed was Clarence Walker.

Clarence Walker was a tall, lanky man in his late fifties who incessantly smoked cigarettes. He wore a low haircut and full mustache and loved to have a conversation, even if he did the majority of the talking. He worked at the Boeing plant as a cook and was well liked among friends for his solid smile and good-humored personality. A combat veteran, he had witnessed friends die fighting in subzero temperatures during the Battle of the Bulge, one of the largest German artillery attacks of World War II. Ironically, it was only after surviving the horrors of Piatt Street that he would undergo psychiatric counseling for several months to cope with the trauma.

211

Clarence and his wife, Irene, who barely escaped their home when the plane hit, quickly informed the interviewers about what actually occurred during recovery efforts:

Let me correct you right now. That was one of the biggest frauds that ever came out. This fellow offered these homes. He had so many houses, and it come to find out that he didn't have nothing but some coops out there that had to be fixed upâjust like my garage which is ready to fall downâand he offered them to us, and the Red Cross, well, we asked them to find us a home and they couldn't find nothing

.

212

Mrs. Walker went on to describe how the Red Cross found them some apartments for eighty-five dollars a month, but it would pay for only one month's rent. Not to mention, the apartments were located in a dilapidated area.

213

Those who had no choice but to stay in the apartments offered by the Red Cross called them “the filthiest place I've been.”

214

The families affected, in many cases, were split up and forced to live wherever they could find shelter. Carpenter and Wesley later concluded in their study, “It is obvious that the Red Cross, while it offered food vouchers in several instances and rendered other amenities, misread the housing needs of the displaced persons.”

215

Victims also soon discovered that the clothes donated were mostly hand-me-downs, in odd sizes, which either needed repair or were so “on the fritz” that they were of use to no one. Furniture was “filthy” and missing pieces. Operation Holiday, which looked so promising just hours after the crash, was quickly discovered to be a “glorified rummage give-away” by most victims.

216

Moreover, few had the wherewithal to retrieve the donated items or anywhere to put them. And despite the air force providing $1,000 in financial aid to individuals, it required proof of identity, property ownership and next of kin (if the victim had perished) before it would pay out any aid money. In many cases, the next of kin resided in other states, identification and property papers were destroyed in the fire and some blacks were understandably hesitant, even suspicious, about signing paperwork from what was perceived then as a “white” government.

217

James Garmon, a former navy aviation machinist and Boeing employee who once ran for state senator, operated Razook's store just yards from the crash site and attempted to ease the difficulties for blacks dealing with the air force claims office.

218

Over 60 percent of his customers were the residents impacted by the tragedy. Garmon was also African American, and because of his intimate knowledge of the black community, the claims office asked for his assistance. According to Garmon, “You couldn't get the people to sign a claim,” especially since “attorneys and the ministers were instructing them never to sign any papers whatsoever.”

219

The majority of uneducated blacks living in this area feared this was some type of final settlement. This, coupled with the air force's requirement of signatures and various forms of proof, drastically delayed the entire process.

The $1,000 grant was also, in reality, much closer to an average of $250 per claim. Five months after the crash, Carpenter and Wesley reported that only

one

family, the Meyers, received a $1,000 grant. This happened only “after much persuasion from their attorney, G. Edmond Hayes.”

220

Carpenter and Wesley concluded that the major source of hesitation by blacks to receive their claims “came from the inertia developed by long frustrating previous struggles with whites. Always under the surface of interviews was the idea, by implication, that âWe're in another situation where we might get taken again.'”

221

There was also an overwhelming feeling that the $6,992.03 reported by the Red Cross in April as its total expenditure on the disaster “filtered out into higher salaries” because it failed to match its performance, given the substantial contributions received.

222

Race was, indeed, a factor, as it had been in almost every area of life in Wichitaâeven in disaster.

Racked with anxiety and uncertainty, the victims of the Piatt disaster could only speculate how this tragedy might have unfolded differently had Raggy 42 fallen just a few blocks east. An unidentified woman in a taped radio interview at the crash scene aptly surmised the dichotomy between the two neighborhoods: in other neighborhoods there were resources, but in the ghetto, “I guess we just have to make do.”

223

11

A DIVIDED CITY AND COUNTRY

One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free

.

âJohn F. Kennedy, 1963

224

The mayday call by Raggy 42 on January 16, 1965, was not the only distress signal ringing that day. Hundreds of feet below the turbulent KC-135, the cityâand, indeed, the countryâwas sending out its own cry for help. America was in trouble; Americans were divided. By the time 1965 was underway, one of the greatest hopes for the progress of civil rights, President John F. Kennedy, was slain; Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was planning what would become the most famous march for equality in Alabama from Selma to Montgomery; American soldiers were entangled in an expanding and deadly Vietnam War; the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were signed into law by the first southern president to be elected in over a century; black homes, churches and businesses were bombed and burned in the South; violent race riots broke out in Watts, California, later that year; and Americans everywhere were pushing for the integration of segregated establishments across the United States.

225

Racial equality had reached an impasse. Neither the passage of laws nor federal troops could fix the problem. As President Kennedy observed, “[L]aw alone cannot make men see right.”

226

Once again, mirroring what took place one hundred years prior, Americans were in the midst of civil war.

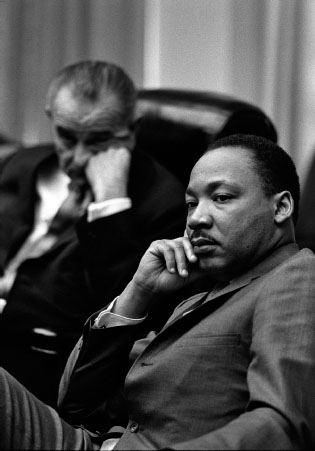

Martin Luther King Jr. at the White House with Lyndon B. Johnson, March 18, 1966.

Lyndon B. Johnson Library

.

It is not possible to fully understand the impact that a massive KC-135 aircraft, laden with jet fuel, has when it crashes into a primarily African American neighborhood in 1965 without first bearing in mind the context of what was taking place in the city of Wichita and in the country itself. When this tragedy befell Wichita, it did so during one of the worst periods of social upheaval in American history: at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. The crash and its effects, which divided the community, were a microcosm for the larger conflict at handâa conflict that burned brighter as the decade progressed. How the nation arrived at this point, the role of Kansas in the Civil Rights Movement and the African American experience in Wichita during 1965 are crucial points to consider when encapsulating this tragedy.

K

ANSAS

: A B

RIEF

R

ESPITE FROM THE

S

OUTH

A seventy-year-old coffin maker from Tennessee led the biggest impetus for free blacks to enter Kansas in the 1870s and 1880s. He had experience placing the bodies of dead slaves who “got out of line” into their graves. He knew all too well the cruelties of slavery and the oppression of blacks in the South following the Civil War.

227

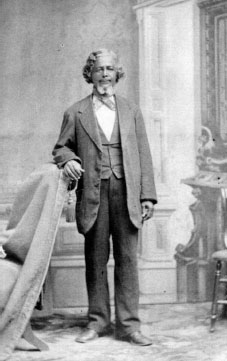

Benjamin “Pap” Singletonâwho had a stern face, a strong jaw and piercing brown eyesâwas a rough, disciplined man. He had seen his share of life. Born and raised in slavery, Singleton led so many blacks out of the South that he once boasted, “I am the whole cause of the Kansas immigration!”

228

Few could argue to the contrary.

Singleton, through his immense work and tenacity in leading blacks from former slave states to Kansas, would eventually become known as the “father of Kansas black immigration.”

229

Singleton wrote numerous letters to the Kansas governor asking for help with the exodus and he traveled extensively back and forth to Tennessee, over hundreds of miles, leading thousands of blacks to establish settlements in Kansas. In his twilight years, he declared, “I have taken my people out in the roads and in the dark places, and looked to the stars of heaven and prayed for the Southern man to turn his heart.”

230

Benjamin “Pap” Singleton.

Kansas Historical Society

.

Not only did migration to Kansas give blacks new freedoms and opportunities, but Singleton also surmised that, by removing blacks from the South, he could create a labor shortage to remind southern whites not to mistreat the people they depended on for production. Granted, the mistreatment of blacks by southerners did not cease, but many oppressed laborers went elsewhere to states like Kansas.

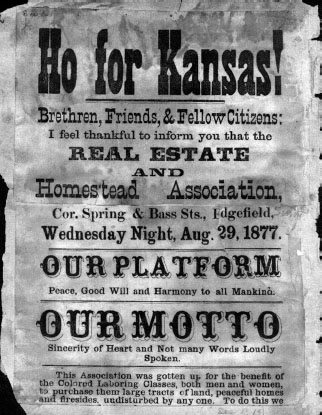

Exodus handbill.

Kansas Historical Society

.

M

IGRATION

Men like Singleton and Henry Adams, another well-known organizer of black migration, were a part of the movement following Reconstruction that brought the first black families to Kansas. After years of bloodshed to determine whether Kansas would become a slave state or free state, in the vacillating conflict known as “Bleeding Kansas,” it finally entered the Union as a free state on the bitterly cold day of January 29, 1861.

231

With the passage of the Homestead Act in 1862, settlers soon crossed the threshold, making Kansas their home. Eight years later, when the first flour mill was established in the city of Wichita to support what had become a thriving wheat industry, the first black family settled there in 1870.

232

The next family arrived in Wichita in 1871, followed by four more in 1872, two in 1874, one in 1875, five in 1876, three in 1878 and 1879 and four in 1880. By 1880, nearly two dozen black families were living in Wichita.

233

These numbers continued to grow over the decades as more migrated to Wichita in search of employment and freedom.