Millions Like Us (26 page)

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Ach, there were lots of good times. And it opened up my life. Mainly, it was the comradeship that made it. I worked with the same group for most of the time I was in the Corps, and I made great friends with them. We were all in the same boat.

Though her forestry work made a huge contribution to the war – providing everything from pit props to coffins, telegraph poles to armaments packaging, Jean was only marginally interested in the war effort:

I don’t think we thought deeply about what we were doing or why we were doing it - we were just

doing

it! We were there to have fun.

But where the job made a real difference was in her own sense of self-worth. The war had turned her into a somebody:

The war changed my life completely. It gave me confidence. I know now that anything men can do, women can do better.

Kay Mellis was another

young Scottish woman who left a life of narrow horizons and through war work discovered a new side to herself. She was billeted in a hostel with seven other Land Army girls, and conditions were as tough for her as for Jean McFadyen. The accommodation was in a courtyard harness-room with horses on one side, a braying donkey on the other and rats everywhere, which chewed their clothes. The work made no concessions to her youth or lack of strength:

We had to do whatever a man could do, there was no question. We thinned turnips with hoes – but the men used to always take the best hoes. And if your hoe was too big, it would rub between your forefinger and your thumb. Sugar beet we had to pull out by hand … We got sores, and calluses; you used lanolin to soothe them.

But three years of back-breaking farm work also boosted Kay’s confidence in her abilities:

At the beginning we were told we were useless – coming from the town with our soft hands and posh Edinburgh way of talking. But I must admit that, when I could thin neeps a bit better, and lift tatties a bit better, it did make me feel really good. To think: ‘Oh, I can do as good as you now.’

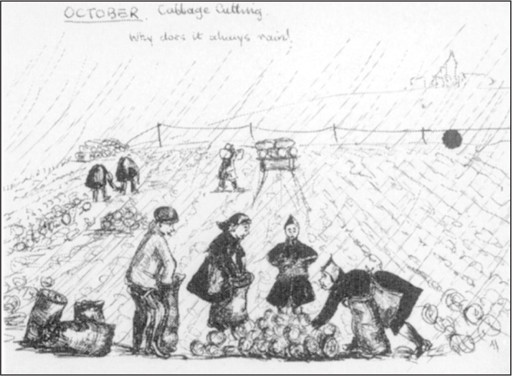

‘Why does it always rain?’ A Kentish land girl’s view of cabbage-cutting. Here as elsewhere, there is no differentiation between men’s and women’s work.

Another propagandising

publication about the Women’s Land Army appeared in 1944. It was written by Vita Sackville-West, who, with her love of the land and keen appreciation of young women clad in boots and breeches, would appear to have been the perfect choice of author for such a work. Sackville-West’s account of the WLA in Scotland complements Jean’s and Kay’s experiences, telling of ‘townies’ lifting potatoes, Scottish shepherdesses, the pleasures and perils of milking a cow and the satisfactions of rat-catching. And she described the life of the Timber Corps girls, romantically cut off from civilisation among the deer and the wild Highland scenery – ‘Man’s foolish war had penetrated even this.’

A less eulogising picture of the Land Army appeared after the war was over.

Shirley Joseph described

her 1946 memoir as ‘an Unofficial Account’. In it she told of insanitary living conditions and lack of fresh food; of working seventy-hour weeks, with one week off a year. She told of dung-spreading, tractor-driving, ploughing, loading and

five o’clock starts. ‘I felt more tired at the end of the day than I had thought humanly possible’ – and yet the farmer who employed her regarded her as a shirker. Surviving as a land girl required, in her view, robustness, genuine love of the country and lack of ambition. ‘It is not necessary to be well educated or intelligent in the Land Army. In fact, the fewer brains and more brawn you have, the more the farmer likes you … Land girls are the lowest form of life in the eyes of many farmers.’ Several other accounts confirm this picture: bullying farmers, misery and exhaustion.

Monica Littleboy held out

on a chicken farm in Norfolk for six months before quitting for the WAAFs. ‘I was working with one man and a boy and thousands of chickens for company … the dust, confusion, dirt and noise had to be seen to be believed … at five o’clock I cycled back 4 miles … worn out and ready for bed.’ The artist

Mary Fedden chose

the Land Army because she thought she would be safe from the bombs, but her Gloucestershire farm was close to an aircraft factory: ‘we were bombed every night for a year … When the farmer was beastly to me I would go into the shed and sit among the calves, and cry,’ she remembered.

But Shirley Joseph conceded that the experience had value. Communal living had made her broad-minded. The social mix encompassed girls from every conceivable walk of life and, exposed to all kinds of explicit narrations, she soon dropped her conventional outlook: ‘If my mother could have overheard some of the conversations I listened to!’ Like Jean McFadyen and Kay Mellis, she felt that her time with the Land Army had educated her, though she did not feel that the experience was likely to be of long-term value:

A girl can’t milk a typewriter any more than she can drive a tractor for a dress shop …

It is true that she will see, in all probability, a new and different side of life. She will undoubtedly be a sounder judge of human nature. She will have learnt self-reliance and self-confidence; and never to take things at their face value …

But such knowledge and experience are not exclusive to those who serve in the Land Army. They can equally well be gained in any of the women’s services.

Officers and Ladies

Shirley Joseph felt the main benefit of her time in the Land Army was its democratising effect, and many of her contemporaries would have agreed that social mobility increased during the war. Before the war, the distinctions between maid and mistress were set in stone.

Patience Chadwyck-Healey would

no more have chatted informally to Jean McFadyen, Pat Bawland or Flo Mahony than she would have fraternised with her mother’s cook. Now in the FANYs Patience, and many like her in the other services, found herself not only polishing the same brass buttons and bashing the same squares as her social ‘inferiors’, but having to question her ingrained feudal assumptions:

During the war it was very interesting. One found oneself on an entirely new level of meeting people. I remember particularly one little person (well, she

was

a little person, actually), and I said something like: ‘Where are you from?’ and she had a slight accent of some sort, and she said ‘Oh I was a parlour maid’. So I was quite interested, and I thought: ‘This is some sort of revolution! Here we are sharing a dormitory together.’

And I learned how nice people like that were. One had never been able to talk to them before. But bit by bit talking to them became the norm. You know, we were all doing a job. In fact, they were very often better at the jobs we were asked to do – you know, when we were asked to clean the room or something.

And then eventually, when you became an officer, you also met women above you, who probably would never have crossed your social horizons – because perhaps they were qualified in business, for example. So one’s rather narrow social circle was hugely expanded. Which was all for the good … It was a sudden jump – people who’d been miles apart

had

to come together and work together.

Patience’s reflections certainly give an indication of social upheaval, though her observation that ‘we’ were just hopeless at cleaning out rooms compared to ‘them’ shows that there was still some way to go. The little parlour maid’s accent was perhaps too much of a giveaway, just as

Christian Oldham in the Wrens

couldn’t help noticing the unhygienic habits of some of her more ‘interesting’ dormitory-mates:

Some were wedded to their vests, which they had been wearing all day, keeping them on under pyjamas before they tucked down for the night. Putting your bra on outside your vest then of course comes naturally. The intermediate stage – washing – was passed over.

Christian, as in love with her morning bath as her dorm-mates were with their malodorous undergarments, found their BO offensive, though she tried to put it delicately:

The vest enthusiasts were rather more prone to this affliction than others.

Many accounts remark on how the ‘lower orders’ were also noticeably afflicted with bad language, crudity and vulgarity. But, quick to redress the balance on such observations, Christian commented that, overall, these were superficialities. Like Patience Chadwyck-Healey, she had grown up with narrow horizons and was glad of the opportunity to meet and mix with girls from across the social spectrum. Could ‘the Colonel’s lady and Judy O’Grady’ ever be sisters? In Christian’s friendships and working relationships there was one common factor – ‘that was their integrity’. It had nothing to do with status, smelly vests or being ‘born on the wrong doorstep’. ‘I just realised that some people were true to their word and some were not.’ But these ex-debutantes were speaking from a position of privilege. (Christian herself had secured her coveted post in the Wrens through the good offices of her grandmother, who played bridge with somebody who happened to be Vera Laughton Mathews’s brother.) It cost them little to speak of settling down harmoniously with parlour maids.

For Audrey Johnson,

a lower-middle-class girl from Leicester, early days with the Wrens served only to remind her that she had joined the elite women’s service:

Impeccable, well-to-do accents rang through the building. ‘Marjorie was at school with you, I understand: and I believe you know the Somebody-hyphen-Somebodies.’ ‘Oh, you’re Rosemary. Daddy told me to keep a lookout for you. He’s at the Admiralty with your uncle.’ Everybody seemed to know somebody of importance …

I knew no-one … I had a feeling that I must be the only girl who had left school at fourteen. But I was not going to mention that to anyone, and night school elocution lessons had helped a bit.

War undoubtedly threw up some strange bed-fellows;

evacuated from Ilford

to Wales between 1939 and 1942, middle-class teenager Nina Mabey had to adapt to some very different ways of life. She was billeted with a series of Welsh ‘aunties’ and ‘uncles’ who often seemed to come from another planet. One family seemed to her almost sub-human. They were curiously deformed, hardly spoke and kept the outside world at bay with permanently locked doors. Another of her hostesses expected Nina to wash and scrub the handkerchiefs her son sent home from college. Encrusted though they were with gluey mucus, she didn’t feel able to refuse this hideous task. In Aberdare the house was full of black beetles and Mrs Jones served pilchards straight from the tin. Nina ate them, lukewarm, while her miner host Mr Jones stood naked in a zinc bath at the other end of the room, scrubbing off the coal dust. One day she found Mrs Jones weeping in desperation after an avalanche of wet coal slurry, flowing off the slag heap behind the house, inundated the kitchen. Appalled at the mess, Nina found a shovel and wheelbarrow to help her clear it up, but Mrs Jones was distraught. ‘It’s not right you should do this kind of dirty work. It’s not a job for an educated girl.’ As well as accustoming her to ‘other people’s funny habits’, these experiences awakened sixteen-year-old Nina’s social conscience. Mr Jones often worked two shifts in twenty-four hours – ‘doing his bit’ for the war effort. ‘What had his country ever done for him?’ Wales, far from being a safe back-water, turned out to be a hotbed of fomenting socialism. Nina went to hear Aneurin Bevan speak, her teachers encouraged a burgeoning awareness of social injustice, and she developed ‘a political allegiance that has informed my life’.

The melting-pot theory of war had an element of truth.

WAAF Flo Mahony

felt that the war had shifted her up the social scale. ‘I think we’ve gone up a class. My family were certainly working-class, but I don’t think I am now. I look on myself as middle-class.’ Countless recollections of joining the services tell of married and single, conscript and volunteer, bank clerk, shop assistant, chambermaid, schoolgirl, business girl, actress and debutante being thrown in together, emerging indistinguishable from each other in a democracy of coders, telegraphists, armourers and plotters, drivers, orderlies, gunnery and signals officers, and kine-theodolite operators.

But a closer reading of such accounts unearths as many instances

of elitism and snobbery, charmed circles and special treatment, rank-pulling and system-working. Though not of their number,

Mavis Lever was well aware

that Bletchley Park was full of manicured debutantes whose daddies had pulled strings for them – ‘No doubt about it, it was a good berth compared to working in a munitions factory.’

Patience Chadwyck-Healey couldn’t bear

the way some of the grander girls got preferential treatment through their high-up connections: ‘I became quite communistic in the end.’

And according to Joan Wyndham,

who had been called up to the WAAFs in 1941, officer rank could only be conferred if you were a bona fide lady: ‘They look out for dirty nails, holes in stockings and try to find out if your mother was a char, and ask you trick questions to see if you say “toilet” or “pardon”.’ ‘Toffs’ were all too easy to spot.

Ex-debutante Wren

Fanny Gore Brown suffered from the coarse language in her ‘Wrenery’ at Dover, and the rough girls there stole her make-up. ‘I was fair game because I talked different, didn’t I?’ And, as we have seen, middle-class Doffy Brewer’s life was made a misery by the taunts of her working-class colleagues.