Millions Like Us (24 page)

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Her husband’s sexual transgressions were no worse than those of innumerable servicemen posted abroad. Though barely twenty-two, Kaye now drew upon a reserve of tolerance and broad-mindedness that would stand her in good stead for the rest of her life. She loved Brian, and she accepted his infidelities. ‘I couldn’t expect him to be faithful, because of being away for so long.’ But Kaye wasn’t prepared to be lonely either.’ There was an officer in the RAF, though I didn’t actually sleep with him … and there was a New Zealander who took me out to dinner at the Bodega … And there was Jack – he was a warrant officer in the army; I met him in the pub, and when he was on leave he used to come and see me, and he did sleep with me. He hoped I would leave Brian. Well – I told Brian about mine, because he told me about his … But he was the first to stray.’

Honesty and goodwill on both sides rescued the Bastin marriage. ‘I’m the sort of person who can take on these problems and deal with them,’ she says today. ‘The important thing is not to make a fuss about everything.’ Unlike those of thousands of separated wives, Kaye’s wartime marriage didn’t end in divorce. In 1938 fewer than 10,000 divorce petitions had been filed, less than half by husbands. By 1945 the numbers would reach 25,000. Over half of these – 14,500 – were filed by husbands, of which about 10,150 (70 per cent) were on the grounds of adultery by their wives. Each case, in that torrent of petitions flooding the courts throughout the 1940s, told its own tale of loneliness, infidelity, adultery, betrayal.

There was Mrs Louis,

a Berkshire woman whose RAF husband came home on leave and, having peremptorily informed her that he would be divorcing her to marry someone else, not only sent a furniture van round to remove all the household goods, but had all the lights ripped out of their fittings.

There was Elizabeth Jane Howard,

who felt she had made a mistake from the outset when she married her husband, Peter Scott (son of the Arctic explorer), but despite many flagrant infidelities

waited till the war was over before divorcing him: ‘He was fourteen years older than me so it was not a success really from the start … but I felt I couldn’t go while he was fighting the war.’

Margaret Perry,

a Nottinghamshire nineteen-year-old, was another who married in haste in 1942; neither Margaret nor her new husband, Roy, had thought things through. Isolated in a miserable lodging in north London, Margaret soon fled back to stay with her mum in Nottingham and got a job in the city’s chief department store; unknown to Roy she fell under the spell of a married RAF officer twice her age, who impressed her with his ‘mature’ ideas about politics and vegetarianism. Margaret, eager to learn but young and bewildered, was easy prey. Later she was conscripted into a munitions factory, where she became fascinated by her boss, Peter, a pacifist – also married. ‘I began to worship [him] in a way that was not good for me. Roy and I began to quarrel violently.’ By 1944 Roy could take no more of his young wife’s infidelities ‘of mind and body’. They parted. ‘He’d had a very raw deal from me.’

Precipitate marriages followed by prolonged absence were putting unendurable strain on relationships. The Mass Observation diarist Shirley Goodhart recorded the distress of a friend whose husband had left her ‘for another girl whom he met abroad. This separation is breaking up many marriages.’ Shirley herself had married her doctor husband, Jack, early in 1941. Soon after that he was sent to India; she would not see him again for four years. Could their marriage survive?

Barbara Cartland worked

as a welfare officer during the war. Her sympathies were with the women, but she was equally non-judgemental about the men:

I was often sorry for the ‘bad’ women … They started by not meaning any harm, just desiring a little change from the monotony of looking after their children, queuing for food and cleaning the house with no man to appreciate them or their cooking.

… and who should blame a man who is cooped up in camp all day or risking his life over Germany for smiling at a pretty girl when he’s off duty? He is lonely, she is lonely, he smiles at her, she smiles back, and it’s an introduction. It is bad luck that she is married, but he means no harm, nor does it cross her mind at first that she could ever be unfaithful to Bill overseas. When human nature takes its course and they fall in love, the home is broken and maybe another baby is on the way, there are plenty of people ready to say it is disgusting and disgraceful. But they hadn’t meant to be like that, they hadn’t really.

Before the war, the press had fed off the public’s prurience about broken marriages. The ‘bolter’, or divorced woman, would have had to outface disapproval or even flee the country to escape guilt and disgrace. In 1941 things had changed; a woman on her own was less likely to be deterred from leaving her husband by the thought of becoming destitute. Probably, as an important part of the workforce, she would be able to support herself. Just as importantly, she would be less afraid of being judged; the Abdication crisis had nudged public opinion a step closer to leniency. But above all, everybody now knew what it felt like to be lonely, worried and frightened, and Barbara Cartland’s compassionate lack of censure was a common reaction to the external pressures imposed by war. Self-righteous condemnation seemed unnecessarily cruel in a world of bombs and shortages.

Some of the stigma was lifting from divorce. Along with modesty and maidenliness, the winds of war were starting to blow away the injustices and misrepresentations that had clung for so long to the lone woman. The ‘old, narrow life’ was becoming broader. Though uncertain, a small flame had been kindled. Was it, perhaps, possible that the cage doors were indeed standing open – that one might emerge from the dusting and cooking and queuing, and step through to one’s heart’s desire? Official recognition that they were ‘essential’ gave a boost to jaded nerves, as women began to see that, after years of being cabbages, they were needed. And under the mantle of total war, everyone’s desires and dreams seemed legitimate, not just men’s.

5 ‘Your Country Welcomes Your Services’

Women in Uniform

Late in the year, the Wiltshire hedges were thick with haws and spindle-berries. The village pond froze solid and then thawed.

At Ham Spray House,

Frances Partridge and her small family kept as far as possible to the everyday routine. There were reviews to write, beehives to repair, a vegetable garden to cultivate. Frances’s diary entry for 16 November 1941 recalled a contented day attending to her son and practising her violin:

R. said how happy he was, so did Burgo and so did I. When I wake these days, in spite of the war and our uneventful life, it is to a pleasurable anticipation of minute things – the books I’m going to read, the letters the post will bring, the look of the outside world.

But invasion was still a fear. They hoarded their tinned food. Every evening at 9 p.m. – in common with families across the country – they huddled round the wireless for the news bulletin. In the desert Rommel’s army was continuing to block the British offensive. The Germans were marching towards Moscow. In the month of November 11,000 Russians starved to death in Leningrad.

On 2 December Churchill outlined proposals for increasing the wartime workforce. Frances’s husband, Ralph, would be affected by the call for men between forty and fifty-one to register for military service; he determined to testify as a Conscientious Objector. At the beginning of that month tension between Japan and America increased dramatically; in response to this threat Britain expanded its Eastern Fleet. Frances felt she was living through an earthquake; the ground she stood on, her familiar pleasures, her values and her deep personal happiness with Ralph seemed to be crumbling and giving way beneath her. On 7 December she wrote:

All the events of today have been blotted out by the evening’s news. Japan has opened war on the U.S.A. with a bang, by an almighty raid on the American Naval and Air Base at Pearl Harbour. No ultimatum, no warning; the damage has been ghastly and casualties extremely heavy. Nothing could have been more unprovoked and utterly beastly.

The world now seemed to be engulfed in war.

But the cares and worries of everyday life still had the power to dominate larger concerns. These included, in her case, the departure of the Partridges’ servant, Joan. When Joan’s boyfriend was posted abroad she went to Frances, white-faced, to tell her, ‘Mrs Partridge, I want to leave and do war work.’ She had been to an aircraft factory in Newbury to see if they would take her on. Frances was aghast. Joan’s misery was plain to see, and she felt powerless:

Of course it is the happiness of not one but hundreds of Joans and hundreds of Gunner Robinsons, thousands, millions I should say – of all nationalities – that is to be sacrificed in this awful pandemonium … We were both too upset to read.

But of course she was also only too aware of the effect Joan’s departure would have on the Ham Spray household:

Our life gets more domestic and agricultural and when Joan goes it may get more so. If only I could cook!

After Joan left she did her best to learn, but there was also the housework. By Christmas Frances was finding that sweeping and dusting were an excellent antidote to cold. It also filled her with a ‘glow of virtue’, and even Ralph washed up and helped to bottle fruit. Her wartime diary reflects on the mindless physical energy it required to scrub the nursery floor, a task ‘I can take no interest in’.

Frances had help from a succession of Joans and Alices and Mrs Ms throughout the war. They came and went intermittently, each time leaving her submerged in domesticity, wringing her hands at the lack of help, frustrated at the boredom of childcare and housework, and by her culinary shortcomings. The Joans and Alices meanwhile were volunteering or being conscripted into the factories, the forces, the farms and the forests.

As early as 1940 a book had appeared entitled

British Women at War

by Peggy Scott, which set out to celebrate women’s contribution to

the war effort. The tone of the book was whistle-while-you-work cheeriness, and its pages were peopled with non-complaining girl guide types who all set to work with a will:

The modern girl with her freedom, her independence, her disregard of public opinion, was vindicated at once in the new war. She fitted into the Navy, Army and Air Force as easily as she had done into a mixed bathing party.

But with the advent of conscription modern girls knew that they would no longer have the luxury of choosing between the services, and many decided to join up while they still could. So what were the factors influencing their decision?

*

For a surprising number it was the clothes. Few of them knew what to expect, so they judged on appearances.

Christian Oldham, the convent-educated

daughter of an admiral, had been to finishing school in France before the war and joined the Wrens in 1940. Years later, when she published an account of her time with the ser-vice, Christian couldn’t decide what to call it, until she mentioned casually to her editor, ‘You know,

I only joined for the hat

.’ They both agreed it would make the perfect title.

Christian Oldham claims to have been ‘hat-minded’ from the age of three. At twenty she was even more susceptible to the flattering double-breasted tailored jacket, svelte skirt and pert tricorne hat that comprised the officers’ uniform. Vera Laughton Mathews, Director of the Wrens, had commissioned the elite fashion designer Edward Molyneux to come up with the look. ‘The effect was a winner,’ according to Christian, and entirely accounted for the huge waiting list of applicants wishing to join:

The great thing was, of course, that the ATS and the WAAFs had these frightful belts which made their bottoms look enormous, whereas the Wrens had this nice straight uniform which concealed your worst points. Joining the Wrens was quite the most fashionable war work.

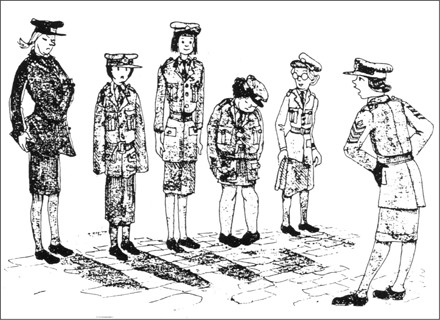

Admittedly, the ATS uniform lacked pulling power: in truth, a single-breasted, belted khaki jacket bulked out with cumbersome pleated pockets did nothing for one’s figure. The WAAFs suffered

from the same defect where pockets and belts were concerned, accentuating hips and bottoms. Fashionable or not, most recruits underwent a reality check once they’d signed up and been issued with their new uniform.

An ATS recruit recalled

that

[the uniform] fitted me about as well as a bell tent, trailing on the floor behind me while my hands groped in sleeves a foot too long. Evidently the army expected its women to be of Amazonian proportions. I was to find that the army had a genius for issuing absurd garments and expecting one to take them seriously.

The ATS recruit who sketched this ‘kitting-out’ session recalled: ‘I do not know how the sizes were worked out, but they all had to be altered.’

And there were universal complaints about frumpy underwear: ‘

The knickers were long-legged

ones: we called them “twilights” and “blackouts” – light blue in summer, darker, knitted ones in winter, plus vests and cotton bras.’ One group of recruits fell about in hysterical merriment at the sight. ‘

Just imagine

anyone thinking we would be seen dead in them!’ They parcelled the woolly knickers up and sent them off to their aunts, an action they regretted in November, at a freezing station somewhere in the Hebrides.