Miracles of Life (21 page)

Authors: J. G. Ballard

Tired of all this, and feeling that the entire wrangle about

drugs was ripe for a small send-up, I suggested to Martin Bax

that

Ambit

should run a competition for the best poem or

short story written under the influence of drugs – a reasonable

suggestion, given the huge claims made for drugs by

rival gurus of the underground. This time Lord Goodman,

legal fixer for the Prime Minister Harold Wilson, denounced

Ambit

for committing a public mischief (a criminal offence)

and in effect threatened us with prosecution. The competition

was conducted seriously, and the drugs involved

ranged from amphetamines to baby aspirin. It was won by

the novelist Ann Quin, for a story written under the influence

of the contraceptive pill.

Another of my suggestions was staged at the ICA, when

we hired a stripper, Euphoria Bliss, to perform a striptease to

the reading of a scientific paper. This strange event, almost

impossible to take in at the time, has stayed in my mind ever

since. It still seems in the true spirit of Dada, and an example

of the fusion of science and pornography that

The Atrocity

Exhibition

expected to take place in the near future. Many of

the imaginary ‘experiments’ described in the book, where

panels of volunteer housewives are exposed to hours of

pornographic films and then tested for their responses (!),

have since been staged in American research institutes.

I must say that I admire Martin Bax for never flinching

whenever I suggested my latest madcap notion. He was, after

all, a practising physician, and Lord Goodman may well have

had friends on the General Medical Council. Martin responded

positively to my wish to bring more science into the

pages of

Ambit

. Most poets were products of English

Literature schools, and showed it; poetry readings were a

special form of social deprivation. In some rather dingy hall

a sad little cult would listen to their cut-price shaman speaking

in voices, feel their emotions vaguely stirred and drift

away to a darkened tube station.

I wanted more science in

Ambit

, since science was reshaping

the world, and less poetry. Asked what my policy was as

so-called prose editor of

Ambit

, I would reply: to get rid of

the poetry. After meeting Dr Christopher Evans, a psychologist

who worked at the National Physical Laboratory, not

far from Shepperton, I asked him to contribute to

Ambit

.

We published a remarkable series of computer-generated

poems, which Martin said were as good as the real thing. I

went further: they were the real thing.

Chris Evans drove into my life at the wheel of a Ford Galaxy,

a huge American convertible that he soon swapped for a

Mini-Cooper, a high-performance car not much bigger than

a bullet that travelled at about the same speed. Chris was the

first ‘hoodlum scientist’ I had met, and he became the closest friend I have made in my life. In appearance he resembled

Vaughan, the auto-destructive hero of my novel

Crash

,

though he himself was nothing like that deranged figure.

Most scientists in the 1960s, especially at a government laboratory,

wore white lab coats over a collar and tie, squinted

at the world over the rims of their glasses and were rather

stooped and conventional. Glamour played no part in their

job description.

Chris, by contrast, raced around his laboratory in

American sneakers, jeans and a denim shirt open to reveal an

Iron Cross on a gold chain, his long black hair and craggy

profile giving him a handsomely Byronic air. I never met a

woman who wasn’t immediately under his spell. A natural

actor, he was at his best on the lecture platform, and played

to his audience’s emotions like a matinee idol, a young

Olivier with a degree in computer science. He was hugely

popular on television, and presented a number of successful

series, including

The Mighty Micro

. Although running a

research department of his own, Chris became an ex officio

publicity manager for the NPL as a whole, and probably the

only scientist in that important institution known to the

public at large.

In private, surprisingly, Chris was a very different man:

quiet, thoughtful and even rather shy, a good listener and an

excellent drinking companion. Some of the happiest hours

in my life have been spent with him in the riverside pubs between Teddington and Shepperton. In many ways his

extrovert persona was a costume that he put on to hide a

strain of diffidence, but I think this inner modesty was what

appealed to the American astronauts and senior scientists he

met during the making of his television programmes. He

was a great lover of America, and especially the Midwest

states, and liked nothing better than flying into Phoenix or

Houston, hiring a convertible and setting off on the long

drive to LA or San Francisco. He liked the easy formulas of

American life. He thoroughly approved of my wish to see

England Americanise itself, and hung California licence

plates over his desk as a first step.

After taking his PhD in psychology at Reading University,

Chris specialised in computers, and spent a year at Duke

University, home to Professor Rhine and the ESP experiments

that involved closed rooms and volunteers guessing

each other’s card sequences. Chris’s American wife, Nancy, a

beautiful and rather remote woman, was Rhine’s secretary

when he met her. ESP experiments were largely discredited

in the 1960s, but I think Chris still had a sneaking hope that

telepathic phenomena existed on some undiscovered level of

the mind. Now and then, as we hoisted our pints and threw

pieces of our cheese rolls to the Shepperton swans, he would

slip some reference to ESP into the conversation, waiting

for my response. He was also surprisingly interested in

Scientology, while claiming to be a complete sceptic. I sometimes wonder if his entire interest in psychology was unconsciously

a quest for a paranormal dimension to mental life.

I often visited Chris’s lab, and admired the American

licence plates and the photographs of him with Aldrin and

Armstrong (this was before the lunar flights in 1969). I was

fascinated by the work his team was doing on visual and

language perception. In the 1970s he was exploring the

possibilities of computerised medical diagnosis, after the

discovery that patients would be far more frank about their

symptoms when talking to a computerised image of a doctor

rather than the doctor himself. Women patients from ethnic

minorities would never discuss gynaecological matters with

a male doctor, but spoke freely to a computerised female

image.

I was sitting in his office in the early 1970s when

something in the waste basket beside his desk caught my eye,

a handout from a pharmaceutical company about a new

antidepressant. Seeing my eyes light up, Chris offered to

send me the contents of his waste basket from then on. Every

week a huge envelope arrived, packed with handouts, brochures,

research papers and annual reports from university

labs and psychiatric institutions, a cornucopia of fascinating

material that fired my imagination. Eventually I stored them

in an old coal bunker outside the kitchen door. Twenty years

later, when I dismantled the bunker, I started reading these

ancient handouts as I rested between axe blows. They were as fascinating and stimulating as they had been when I first

read them.

Chris’s death from cancer in 1979 was a tragic loss to his

family and friends, all of whom have vivid memories of him.

In 1964 Michael Moorcock took over the editorship of the

leading British science fiction magazine,

New Worlds

,

determined to change it in every way he could. For years we

had carried on noisy but friendly arguments about the right

direction for science fiction to take. American and Russian

astronauts were carrying out regular orbital flights in their

spacecraft, and everyone assumed that NASA would land

an American on the moon in 1969 and fulfil President

Kennedy’s vow on coming to office. Communications satellites

had transformed the media landscape of the planet,

bringing the Vietnam War live into every living room.

Surprisingly, though, science fiction had failed to prosper.

Most of the American magazines had closed, and the sales of

New Worlds

were a fraction of what they had been in the

1950s. I believed that science fiction had run its course, and

would soon either die or mutate into outright fantasy. I flew

the flag for what I termed ‘inner space’, in effect the psychological

space apparent in surrealist painting, the short stories

of Kafka, noir films at their most intense, and the strange,

almost mentalised world of science labs and research institutes where Chris Evans had thrived, and which formed the

setting for part of

The Atrocity Exhibition

.

Moorcock approved of my general aims, but wanted to go

further. He knew that I responded strongly to 1960s London,

its psychedelia, bizarre publishing ventures, the breaking-

down of barriers by a new generation of artists and photographers,

the use of fashion as a political weapon, the youth

cults and drug culture. But I was 35 and bringing up three

children in the suburbs. He knew that however much I

enjoyed his parties, I had to drive home and pay the baby-

sitter. He was ten years younger than me, the resident guru

of Ladbroke Grove and an important figure and inspiration

on the music scene. It was all this counter-cultural energy

that he wanted to channel into

New Worlds

. He knew that an

unrestricted diet of psychedelic illustrations and typography

would soon become tiring, and responded to my suggestion

that he dim the LSD strobe lights a little and think in terms

of British artists such as Richard Hamilton and Eduardo

Paolozzi.

I still remembered the 1956 exhibition at the Whitechapel

Gallery, This is Tomorrow, and I regularly visited the ICA in

Dover Street. Many of its shows were put on by a small

group of architects and artists, among them Hamilton and

Paolozzi, who formed a kind of ideas laboratory, teasing out

the visual connections between Egyptian architecture and

modern refrigerator design, between Tintoretto ‘crane-shots’

and the swooping camera angles of Hollywood blockbusters.

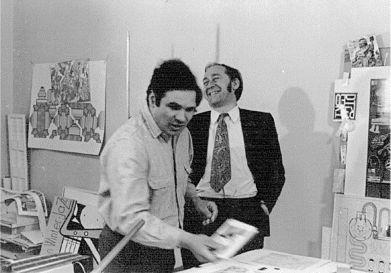

In Eduardo Paolozzi’s Chelsea studio, 1968

.

All this was closer to science fiction, in my eyes, than the

tired images of spacecraft and planetary landscapes in s-f

magazines.

I remembered that in the 1950s Paolozzi had remarked in

an interview that the s-f magazines published in the suburbs

of Los Angeles contained more genuine imagination than

anything hung on the walls of the Royal Academy (still in its

Munnings phase). With Moorcock’s approval, I contacted

Paolozzi, whose studio was in Chelsea, and he invited us to

visit him.

We got on famously from the start. In many ways Paolozzi

was an intimidating figure, a thuggish man with a sculptor’s

huge arms and hands, a strong voice and assertive manner. But his mind was light and flexible, he was a good listener

and adept conversationalist with a keen and well-stocked

mind. Original ideas tripped off his tongue, whatever the

subject, and he was always pushing at the edges of some

notion that intrigued him, exploring its possibilities before

filing it away. A woman-friend I introduced to him

exclaimed: ‘He’s a minotaur!’ but he was a minotaur who was

a judo expert and light on his feet.

He and I became firm friends for the next thirty years, and

I regularly visited his studio in Dovehouse Street. I think we

felt at ease with each other because we were both, in our

different ways, recent immigrants to England. Paolozzi’s

Italian parents had settled in Edinburgh before the war,

where they ran an ice cream business. After art school he left

Scotland and attended the Slade in London, quickly established

himself with his first one-man show, and then left for

Paris for two years, meeting Giacometti, Tristan Tzara and

the surrealists. He always insisted that he was a European

and not a British artist. My impression is that as an art student

he had felt deeply frustrated by the limitations of the

London art establishment, though by the time I knew him he

was well on the way to becoming one of the tallest pillars in

that establishment.

Everyone who knew him will agree that Eduardo was a

warm and generous personality, but at the same time

remarkably quick to pick a quarrel. Perhaps this touchiness

drew on the deep personal slights he suffered as an Italian boy in wartime Edinburgh, but he fell out with almost all his

close friends, a trait he shared with Kingsley Amis. One of his

disconcerting habits was to give his friends valuable presents

of pieces of sculpture or sets of screen-prints and then, after

some largely imagined slight, demand the presents back. He

fell out spectacularly with the Smithsons, his close friends

and collaborators on This is Tomorrow. After giving them

one of his great Frog sculptures, he later informed them that

he wanted it returned; when they refused, he went round to

their house at night and tried to dig it out of their garden.

Their friendship, needless to say, never recovered.