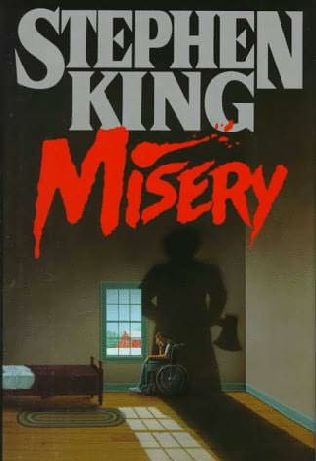

S t e p h e n

KING

MISERY

Hodder & Stoughton

Copyright © 1987 by Stephen King

First published in Great Britain in 1987 by Hodder and Stoughton Limited

First New English Library edition 1988

Eighteenth impression 1992

British Library C.I.P.

King, Stephen

1947-

Misery.

I. Title

813'.54[F] PS3561:1483

ISBN 0 450 41739 5

The characters and situations n this book are entirely imaginary and bear no relation to any real

person or actual happenings.

The right of Stephen King to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanically, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without either the prior permission in writing from the publisher or a licence, permitting restricted copying. In the United Kingdom such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 9HE.

Printed and bound in Great Britain for Hodder and Stoughton Paperbacks, a division of Hodder and Stoughton Ltd., Mill Road, Dunton Green, Sevenoaks, Kent TNI3 2YA. (Editorial Office: 47 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP) by Cox & Wyman Ltd., Reading, Berks. Photoset by Rowland Phototypesetting Limited, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk.

This is for Stephanie and Jim Leonard,

who know why.

Boy,

do

they.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

'King of the Road' by Roger Miller. © 1964 Tree Publishing co., Inc. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission of the publisher.

'The Collector' by John Fowles. © 1963 by John Fowles. Reproduced by permission of Jonathan Cape Ltd.

'Those Lazy, Hazy, Crazy Days of Summer' by Hans Carste and Charles Tobias. © 1963 ATV Music. Lyrics reproduced by permission of the publisher.

'Girls Just Want to Have Fun'. Words and music by Robert Hazard. © Heroic Music. British Publishers: Warner Bros. Music Ltd. Reproduced by kind permission.

'Santa Claus is comin' to Town' by Haven Gillespie and J. Fred Coots. © 1934, renewed 1962 Leo Feist Inc. Rights assigned to SBK Catalogue Partnership. All rights controlled and administered by SBK Feist Catalogue Inc. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. Used by permission.

'Fifty Ways to Leave Your Lover' by Paul Simon. Copyright © 1975 by Paul Simon. Used by permission.

'Chug-a-Lug' by Roger Miller. © 1964 Tree Publishing Co., Inc. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission of the publisher.

'Disco Inferno' by Leroy Green and Ron 'Have Mercy' Kersey. Copyright © 1977 by Six Strings Music and Golden Fleece Music; assigned to Six Strings Music, 1978. All rights reserved.

goddess

Africa

I'd like to gratefully acknowledge the help of three medical I people who helped me with the factual material in this book.

They are:

Russ Dorr, PA

Florence Dorr, RN

Janet Ordway, MD and Doctor of Psychiatry

As always, they helped with the things you don't notice. If you see a glaring error, it's mine.

There is, of course, no such drug as Novril, but there are several codeine-based drugs similar to it, and, unfortunately, hospital pharmacies and medical practice dispensaries are sometimes lax in keeping such drugs under tight lock and close inventory.

The places and characters in this book are fictional.

S.K.

Part I

Annie

'When you look into the abyss, the abyss also looks into you.'

— Friedrich Nietzsche

1

umber whunnnn

yerrrnnn umber

whunnnn

fayunnnn

These sounds: even in the haze.

2

But sometimes the sounds — like the pain — faded, and then there was only the haze. He remembered darkness solid darkness had come before the haze. Did that mean he was making progress? Let there be light (even of the hazy variety), and the light was good, and so on and so on? Had those sounds existed in the darkness? He didn't know the answers to any of these questions. Did it make sense to ask them? He didn't know the answer to that one, either

The pain was somewhere below the sounds. The pain was east of the sun and south of his ears. That was all he

did

know.

For some length of time that seemed very long (and so

was,

since the pain and the stormy haze were the only two things which existed) those sounds were the only outer reality. He had no idea who he was or where he was and cared to know neither. He wished he was dead, but through the pain-soaked haze that filled his mind like a summer storm-cloud, he did not know he wished it.

As time passed, he became aware that there were periods of non-pain, and that these had a cyclic quality. And for the first time since emerging from the total blackness which had prologued the haze, he had a thought which existed apart from whatever his current situation was. This thought was of a broken-off piling which had jutted from the sand at Revere Beach. His mother and father had taken him to Revere Beach often when he was a kid, and he had always insisted that they spread their blanket where he could keep an eye on that piling, which looked to him like the single jutting fang of a buried monster. He liked to sit and watch the water come up until it covered the piling. Then, hours later, after the sandwiches and potato salad had been eaten, after the last few drops of Kool-Aid had been coaxed from his father's big Thermos, just before his mother said it was time to pack up and start home, the top of the rotted piling would begin to show again — just a peek and flash between the incoming waves at first, then more and more. By the time their trash was stashed in the big drum with KEEP YOUR BEACH CLEAN stencilled on the side, Paulie's beach-toys picked up

(that's my name Paulie I'm Paulie and tonight ma'll put Johnson's Baby Oil on my sunburn

he thought inside the thunderhead where he now lived)

and the blanket folded again, the piling had almost wholly reappeared, its blackish, slimesmoothed sides surrounded by sudsy scuds of foam. It was the tide, his father had tried to explain, but he had always known it was the piling. The tide came and went; the piling stayed. It was just that sometimes you couldn't see it. Without the piling, there w

as

no tide.

This memory circled and circled, maddening, like a sluggish fly. He groped for whatever it might mean, but for a long time the sounds interrupted.

fayunnnn

red everrrrrythinggg

umberrrrr whunnnn

Sometimes the sounds stopped. Sometimes

he

stopped.

His first really clear memory of this

now

, the

now

outside the storm-haze, was of stopping, of being suddenly aware he just couldn't pull another breath, and that was all right, that was good, that was in fact just peachy-keen; he could take a certain level of pain but enough was enough and he was glad to be getting out of the game.

Then there was a mouth clamped over his, a mouth which was unmistakably a woman's mouth in spite of its hard spitless lips, and the wind from this woman's mouth blew into his own mouth and down his throat, puffing his lungs, and when the lips were pulled back he smelled his warder for the first time, smelled her on the outrush of the breath she had forced into him the way a man might force a part of himself into an unwilling woman, a dreadful mixed stench of vanilla cookies and chocolate ice-cream and chicken gravy and peanut-butter fudge.

He heard a voice screaming, 'Breathe, goddammit!

Breathe

, Paul!'

The lips clamped down again. The breath blew down his throat again. Blew down it like the dank suck of wind which follows a fast subway train, pulling sheets of newspaper and candywrappers after it, and the lips were withdrawal, and he thought

For Christ's sake don't let any of it

out through your nose

but he couldn't help it and oh that stink,

that stink

that

fucking STINK.

'Breathe, goddam you!'

the unseen voice shrieked, and he thought

I will, anything, please just

don't do that anymore, don't infect me anymore,

and he

tried,

but before he could really get started her lips were clamped over his again, lips as dry and dead as strips of salted leather, and she raped him full of her air again.

When she took her lips away this time he did not

let

her breath out but

pushed

it and whooped in a gigantic breath of his own. Shoved it out. Waited for his unseen chest to go up again on its own, as it had been doing his whole life without any help from him. When it didn't, he gave another giant whooping gasp, and then he was breathing again on his own, and doing it as fast as he could to flush the smell and taste of her out of him.

Normal air had never tasted so fine.

He began to fade back into the haze again, but before the dimming world was gone entirely, he heard the woman's voice mutter: 'Whew! That was a close one!'

Not close enough,

he thought, and fell asleep.

He dreamed of the piling, so real he felt he could almost reach out and slide his palm over its green-black fissured curve.

When he came back to his former state of semi-consciousness, he was able to make the connection between the piling and his current situation — it seemed to float into his hand. The pain wasn't tidal. That was the lesson of the dream which was really a memory. The pain only

appeared

to come and go. The pain was like the piling, sometimes covered and sometimes visible, but always there. When the pain wasn't harrying him through the deep stone grayness of his cloud, he was dumbly grateful, but he was no longer fooled — it was still there, waiting to return. And there was not just

one

piling but

two

; the pain was the pilings, and part of him knew for a long time before most of his mind had knowledge of knowing that the shattered pilings were his own shattered legs.

But it was still a long time before he was finally able to break the dried scum of saliva that had glued his lips together and croak out 'Where am I?' to the woman who sat by his bed with a book in her hands. The name of the man who had written the book was Paul Sheldon. He recognized it as his own with no surprise.

'Sidewinder, Colorado,' she said when he was finally able to ask the question. 'My name is Annie Wilkes. And I am — '

'I know,' he said. 'You're my number-one fan.' 'Yes,' she said, smiling. 'That's just what I am.'

3

Darkness. Then the pain and the haze. Then the awareness that, although the pain was constant, it was sometimes buried by an uneasy compromise which he supposed was relief. The first real memory: stopping, and being raped back into life by the woman's stinking breath.

Next real memory: her fingers pushing something into his mouth at regular intervals, something like Contac capsules, only since there was no water they only sat in his mouth and when they melted there was an incredibly bitter taste that was a little like the taste of aspirin. It would have been good to spit that bitter taste out, but he knew better than to do it. Because it was that bitter taste which brought the high tide in over the piling.

(PILINGS its PILINGS there are TWO okay there are two fine now just hush just you know hush

shhhhhh)

and made it seem gone for awhile.

These things all came at widely spaced intervals, but then as the pain itself began not to recede but to erode (as that Revere Beach piling must itself have eroded, he thought, because nothing is forever — although the child he had been would have scoffed at such heresy), outside things began to impinge more rapidly until the objective world, with all its freight of memory, experience, and prejudice, had pretty much re-established itself. He was Paul Sheldon, who wrote novels of two kinds, good ones and best-sellers. He had been married and divorced twice. He smoked too much (or had before all this, whatever 'all this' was). Something very bad had happened to him but he was still alive. That dark-gray cloud began to dissipate faster and faster. It would be yet awhile before his number-one fan brought him the old clacking Royal with the grinning gapped mouth and the Ducky Daddles voice, but Paul understood long before then that he was in a hell of a jam.