Most Talkative: Stories From the Front Lines of Pop Culture (4 page)

Read Most Talkative: Stories From the Front Lines of Pop Culture Online

Authors: Andy Cohen

Things weren’t much better on TV. This was pre–

Real World

and

Will and Grace

and Bravo, so basically you had Paul Lynde being a mean queen in the center square and Charles Nelson Reilly kibitzing with Brett Somers on

Match Game

—hardly role models for a kid. So, like many a young gayling, I gravitated toward strong, outsized female personalities—on-screen and off.

As I got older, more and more of my close friends were women. I got involved in their friendship falling-outs and stirred up plenty of shit between them. Jackie Greenberg and Jeanne Messing were pre-Housewives boot camp for me. They were my training wheels, “Li’l Housewives” if you will—lots of entertainment and flash and turmoil packed into training bras and junior high botherations, and I was happiest hanging out with—and in the middle of—them. I was constantly putting my foot in it, telling one something that the other said about her, getting involved where I shouldn’t in plans and invitations and parties, and then, when I tried to keep secrets, I’d be punished for favoring one over the other.

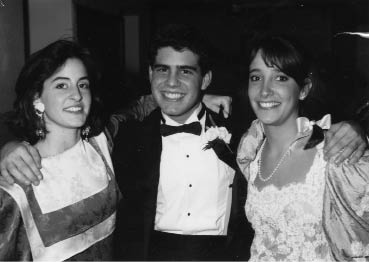

At the prom with the Li’l Housewives, Jeanne and Jackie

In the junior high school social landscape, I was Switzerland, pleasantly popular, and had a self-preservative skill of deflecting attention away from myself by getting involved in other people’s conflicts instead. No one, upon no one, knew that I had my own intense drama roiling just under the surface of my skin. At least that’s what I assumed.

One Sunday in eighth grade, I went over to Jackie’s to play Atari with her. Her mom gave me a ride to Glaser’s Pharmacy and I was standing on the corner waiting to cross the street as she and Jackie sat in the car at a red light. I was leaning on the lamppost in an apparently unmasculine way.

Jackie looked at me and turned to her mother and said something. They laughed. Sensing that I knew exactly what they were chuckling about, I walked over to the car and asked what was funny. Jackie didn’t want to answer at first but then hesitantly responded, “I think that when you grow up, you are going to be a homosexual.”

The light turned, they drove off, and I just stood there in traffic. I realized that my friend had only said something I already knew was true. I also realized that from that minute on, nothing would ever be the same for me. Because now, ready or not, I actually was what I was afraid I was. I was overcome with anger that I had to deal with this truth. That my life was now destined to be clandestine and covert. I didn’t blame Jackie. Being gay was a secret I had kept from everyone, including myself, like a lock without a key. Jackie had merely shown up with a set of verbal bolt-cutters. It’s ironic, of course: All that trouble my motor-mouth caused me, all the annoyance it caused others, and the biggest disturbance of all was caused by what I wasn’t saying. In those days, and at that age, it was not freeing to know that I was gay. It was tragic. Even at that age, I had an inkling of the tough road that might lie ahead for someone like me. At that point in our culture, there were black heroes, women heroes, Latino heroes, but there were no homosexual heroes. Even Paul Lynde was in the closet. (Of course, we hadn’t seen anything yet; AIDS was still around the corner.) I walked home, sobbing my heart out the whole way.

After that, I barely allowed myself to think of “it” during the day. Late at night, though, I would lie awake thinking about my future, the inevitability of my sexuality, and the improbability that anyone would accept me once they knew. I really believed my life would be over once I came out and that this happy kingdom in which I lived would fall to pieces. Or that I would.

CHAINS OF LOVE

By the time I was a senior in high school, I’d established myself to Jeanne, Jackie, and everybody else as—for lack of a better phrase—one of the girls. Boy-girl non-romantic best-friendships were unusual for that time, at least in my circles; nonetheless I was always surrounded by women, a circumstance that prepared me well for my life today. I had guy friends, too, and was popular—president of the student body and voted (big shocker) Most Talkative and (irritatingly, but not exactly shockingly) Biggest Gossip in my senior class. (I was pissed I didn’t get Best Dressed, but that’s another story.) Looking at me, you’d have thought I had it all together. But, without getting too Afterschool Special about it, underneath the gregarious exterior was a whole other story.

Late in high school, Jackie’s parents went on vacation and asked me to stay with her, to look after her and their house. My mom was mystified. A boy staying alone with a girl? What kind of parents would allow such a thing? “Why would you trust your DAUGHTER with my SON?” she asked Jackie’s mother, Jan. After a pause that was way more pregnant than I would ever get Jackie, even alone together for a week, Jan said to my mom, “Andy’s … safe.”

She was right: I was “safe,” in that way. Of course, I didn’t feel very safe. I felt like if anyone found out my secret, I was done for. But for now, no one knew I was gay, and I played right along with the normal high school shenanigans, such as deciding to take magic mushrooms with some friends and go see Eddie Murphy live in concert.

Like everybody, I had loved Eddie Murphy on

Saturday Night Live

. Unfortunately, his live routine differed from his television shtick; namely in that it mostly consisted of ridiculing gay people. Every other word out of his mouth was “faggot.” And with each and every gay joke, the crowd went wild. They loved it. My friends loved it. I was surrounded by thousands of people in hysterics, and they were all laughing at “faggots.” And ipso facto, laughing at me. Unfortunately, the drugs I was on didn’t act as any sort of emotional buffer, but instead like a magnifying glass intensifying the huge beam of hate and mocking cackles trained on me. I ran out of the arena and into the bathroom, where I spent most of the concert in a stall, rocking back and forth wishing and praying that I could somehow unzip my skin and throw it away. I wanted to walk out of that bathroom a completely different person, and yet I knew I couldn’t.

When my legs finally stopped shaking enough for me to stand and leave the stall, an alarmed stranger looked at me: “Are you okay? You look like you don’t feel right.” I saw my reflection in the mirror. My pink Polo button-down shirt was drenched with sweat. I splashed cold water on my face and rejoined my friends while Eddie Murphy continued to merrily spew his best faggot material. (Though I would never be able to laugh at Eddie Murphy’s comedy after that night, rest assured I was highly entertained years later in 1997 when police pulled him over with a transvestite prostitute in West Hollywood.) Watching my friends cheer Murphy on that night reinforced my secret fear that homophobic bigotry was perfectly acceptable. It also reinforced that I should never do mushrooms again, and I haven’t. I do love me a mushroom pizza, though.

* * *

When it came time to go to college, I chose Boston University because of everything it wasn’t. Its social fabric wasn’t dependent on a fraternity system. It wasn’t built around a campus. It wasn’t the only thing going in a small town. It wasn’t anything like St. Louis. It was urban, with a good communications school and, I’d found out on the sly, a semblance of a gay community. Not that I was rushing out of the closet yet, but I needed to know that if I came out (or was pushed out), there’d be a safety net there to catch me. My two girlfriends Jackie and Kari decided to go, too, and so off we went from St. Louis to Boston in the fall of 1986.

Over orientation weekend I was randomly assigned a dorm room with a guy who would become, thank God, my best friend, like a brother, and—some would say—the straight version of me: Dave Ansel. Dave had arrived in the room first and dropped off his duffel bag. When I got there and saw his bag, I did what any self-respecting freshman would do: I opened it up and snooped around. I found the same pair of Vuarnet sunglasses as I had and the same kind of paisley boxers I wore. When I returned to the room later, Dave was there.

“Hello, Louis,” he said. Not only had he read my luggage tags (with my dad’s name on them), but he soon confessed that he, too, had snooped in my bag. We bonded over our lack of boundaries immediately, and as suburban Jewish boys whose families were both in the food business, we had even more in common. From that day on, we were together 24/7. It was a new kind of friendship for me. He was the first guy to tell me he loved me; it was a platonic, brotherly love and we were deep in it. He told me everything and I listened. The one hitch was that during our hours-long late night talks, Dave offhandedly peppered the conversation with a catalog of gay slurs. Which meant that while I was getting to know every detail about him, he didn’t really know who I was at all. It was a kind of torture, feeling that close to someone but not being ready to tell him the truth. And as the months passed, I often wondered: Would he ever be ready to hear it? And would I ever be ready to tell?

For most college kids, the point of going to Europe for a semester is either to experience a foreign culture or maybe to figure out what you want to do with the rest of your life. I saw it as an opportunity to convince my nearest and dearest that I was a raging heterosexual. But fate was against me.

Before I began BU’s London Programme (that’s how they spelled it, and it bugs me to this very day), I traveled through Europe for a month with Jackie. Apparently, her mother’s conviction that I was “safe” still applied, because Jackie and I had already had one amazing trip together, escaping Boston freshman year to jet off to Manhattan. It was my first trip to New York, and every direction I turned, I ran into a place I’d seen in a movie or on TV, bigger and better than I ever imagined. The first time we left Jackie’s parents’ pied-à-terre, we had only walked just a couple blocks, and who came toward us but Andy Warhol. We screamed when he walked by. To this day I can’t believe that I saw Andy Warhol on my first ever day in New York City; it seemed to portend something about my future and what New York had in store for me. (If he were alive today, I’d like to think Warhol would be painting the Housewives.)

The summer before my London semester, Jackie and I Eurailed our way through France, Spain, and Italy. Then she had to go back to St. Louis. For the first time in my life, I was completely alone somewhere far away, which made me feel scared and liberated all at once. I spent a couple of weeks doing whatever I wanted. Everyone back home surely assumed that I was hiking and seeing the sights, but what I was really doing was visiting a bunch of gay bars in Florence and Rome. It wasn’t my first time in a gay bar—I’d been to a few in Boston and once or twice in St. Louis—but in Europe I wasn’t terrified that someone was going to see me and turn me in to the authorities, or (worse) tell my parents. The freedom felt great. In retrospect, when I think of myself in those bars, I realize that I was a twenty-year-old freshly plucked chicken just out of the cage, and it’s a miracle I got out of there alive. But that’s giving me all sorts of credit, when I deserve none. The truth is, I had absolutely no game. First of all, and no small matter: my hair. I’d spent the earlier part of that summer following the Grateful Dead around and was now growing my hair out so I could put it in a ponytail. Have you ever seen a pony with kinky hair? No. My attempt was just a curly, fro-y mess. Making matters worse, I was draped in tie-dye, and my personal hygiene was questionable, even by European standards.

My fortunes changed in Paris. (Isn’t that always the way?) I had a two-day romance with a dude named Jean-Marie; he didn’t speak English and I didn’t speak French, so we conversed in bad, broken Spanish. We had not a thing in common, but it was the most romantic two days of my life. He would point to things and say, in Spanish, “This is a very typical French building.” Or “Summers in France are very warm.” Scintillating! I bet I wouldn’t last an hour with him today without having a narcoleptic seizure, but at the time I thought he was a poet. His apartment was the size of a Tic Tac, and despite its being a complete hotbox, I don’t recall hot water actually being readily available; in fact I have a faint recollection of something (nonsexual) having to do with a teakettle. I thought it was

totalmente

quaint. He was handsome and sweet and had a big Parisian nose. But more importantly, he liked me. We held hands under the dinner table. The whole thing felt like a fantasy. In my heart, there was no turning back.