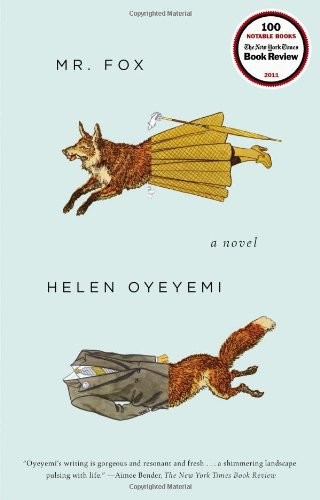

Mr. Fox

Authors: Helen Oyeyemi

Table of Contents

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York,

New York 10014, USA • Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton

Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) • Penguin Books Ltd,

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England • Penguin Ireland,

25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin

Books Ltd) • Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell

Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of

Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) • Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd,

11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017,

India • Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale,

North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson

New Zealand Ltd) • Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd,

24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York,

New York 10014, USA • Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton

Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) • Penguin Books Ltd,

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England • Penguin Ireland,

25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin

Books Ltd) • Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell

Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of

Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) • Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd,

11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017,

India • Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale,

North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson

New Zealand Ltd) • Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd,

24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Oyeyemi, Helen.

Mr. Fox / Helen Oyeyemi.

p. cm.

Mr. Fox / Helen Oyeyemi.

p. cm.

ISBN : 978-1-101-54786-1

1. Authorship—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6115.Y49M

823’.92—dc22

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For my Mr. Fox

(whoever you are)

In the darkness they wondered if they could do it, and knew they had to try to do it.

MARY OLIVER

M

ary Foxe came by the other day—the last person on earth I was expecting to see. I’d have tidied up if I’d known she was coming. I’d have combed my hair. I’d have shaved. At least I was wearing a suit; I strive for a sense of professionalism. I was sitting in my study, writing badly, just making words on the page, waiting for something good to come through, some sentence I could keep. It was taking longer that day than it usually did, but I didn’t mind. The windows were open. I was sort of listening to something by Glazunov; there’s a symphony of his you can’t listen to with the windows closed, you just can’t. Well, I guess you could, but you’d get agitated and run at the walls. Maybe that’s just me.

ary Foxe came by the other day—the last person on earth I was expecting to see. I’d have tidied up if I’d known she was coming. I’d have combed my hair. I’d have shaved. At least I was wearing a suit; I strive for a sense of professionalism. I was sitting in my study, writing badly, just making words on the page, waiting for something good to come through, some sentence I could keep. It was taking longer that day than it usually did, but I didn’t mind. The windows were open. I was sort of listening to something by Glazunov; there’s a symphony of his you can’t listen to with the windows closed, you just can’t. Well, I guess you could, but you’d get agitated and run at the walls. Maybe that’s just me.

My wife was upstairs. Looking at magazines or painting or something, who knows what Daphne does. Hobbies. The symphony in my study was as loud as it could be, but that was nothing new, and she’s never complained about all the noise. She doesn’t complain about anything I do; she is physically unable to. That’s because I fixed her early. I told her in heartfelt tones that one of the reasons I love her is because she never complains. So now of course she doesn’t dare complain.

Anyway, I’d left the study door open, and Mary slipped in. Without looking up, I smiled gently and murmured, “Hello, honey . . .” I thought she was Daphne. I hadn’t seen her in a while, and Daphne was the only other person in the house, as far as I was aware. When she didn’t answer, I looked up.

Mary Foxe approached my desk with her hand stuck out. She wanted to shake hands. Shake hands! My longabsent muse saunters in for a handshake—I threw my telephone at her. I snatched it off the desk and the socket spat out the wire that connected it to the wall and I hurled the thing. She dodged it neatly. The phone landed on the floor beside my wastepaper can and jangled for a few seconds. I guess it was a halfhearted throw.

“Your temper,” Mary said.

“What’s it been—six, seven years?” I asked.

She drew up a chair from a corner of the room, picked up my globe, and sat opposite me, spinning oceans around and around on her lap. I watched her and I couldn’t think straight. It’s the way she moves, the way she looks at you. I guess her English accent helps, too.

“Seven years,” she agreed. Then she asked me how I’d been. Real casual, like she already knew how I’d answer.

“Same as always—in love with you, Mary,” I told her. I wished to hell I wouldn’t keep telling her that. I don’t think it’s even true. But whenever she’s around I feel as if I should give it a try. I mean, it would be interesting if she believed me.

“Really?” she asked.

“Really. You’re the only girl for me.”

“The only girl for you,” she said, and laughed at the ceiling.

“Go ahead and laugh—hurt my feelings . . . what do you care,” I said mournfully, enjoying myself.

“Oh, your

feelings

. . . well. Let’s go further in, Mr. Fox. Would you love me if I were your husband and you were my wife?”

feelings

. . . well. Let’s go further in, Mr. Fox. Would you love me if I were your husband and you were my wife?”

“This is dumb.”

“Would you, though?”

“Well, yes, I could see that working out.”

“Would you love me if . . . we were both men?”

“Uh . . . I guess so.”

“If we were both women?”

“Sure.”

“If I were a witch?”

“You’re enchanting enough as it is.”

“If you were my mother?”

“No more,” I said. “I’m crazy about you, okay?”

“Oh, you don’t love me,” Mary said. She undid the collar of her dress and bared her neck. “You love that,” she said. She unbuttoned further and cupped her breasts. She pushed her skirt up past the knees, past the thighs, higher, and we both looked at her smoothness, her softness, her lace frills. “You love that,” she said.

I nodded.

“This is all you love,” she said, pulling her own hair, slapping her own face. If it wasn’t for the serenity in her eyes I would’ve thought she’d lost her mind. I stood up, to stop her, but the second I did, she stopped of her own accord.

“I don’t want you like this. You have to change,” she said.

The symphony ended, and I went to the Victrola and started it up again.

“I have to change? You mean you want to hear me say I love you for your”—I allowed myself to smirk—“soul?”

“It’s nothing to do with that. You simply have to change. You’re a villain.”

I waited a moment, to see if she was serious and whether she had anything to add. She was, and she didn’t. She stared at me—really came on with the frost, like she hated me. I whistled.

“A villain, you say. Is that so? I’m at church nearly every Sunday, Mary. I slip beggars change. I pay my taxes. And every Christmas I send a check to my mother’s favourite charity. Where’s the villainy in that? Nowhere, that’s where.”

My study door was still open, and I began listening out for my wife. Mary rearranged her clothes so that she looked respectable. There was a brief but heavy silence, which Mary broke by saying, “You kill women. You’re a serial killer. Can you grasp that?”

Of all the—

I hadn’t seen that one coming.

She walked up to my desk and picked up one of my notepads, read a few lines to herself. “Can you tell me why it’s necessary for Roberta to saw off a hand and a foot and bleed to death at the church altar?” She flipped through a couple more pages. “Especially given that this other story ends with Louise falling to the ground riddled with bullets, the mountain rebels having mistaken her for her traitorous brother. And

must

Mrs. McGuire hang herself from a door handle because she’s so afraid of what Mr. McGuire will do when he gets home and finds out that she’s burnt dinner? From a door handle? Really, Mr. Fox?”

must

Mrs. McGuire hang herself from a door handle because she’s so afraid of what Mr. McGuire will do when he gets home and finds out that she’s burnt dinner? From a door handle? Really, Mr. Fox?”

I found myself grinning—the complete opposite of what I wanted my face to do. Scornful and stern, I told my face. Scornful and stern. Not sheepish . . .

“You have no sense of humour, Mary,” I said.

“You’re right,” she said. “I don’t.”

I tried again: “It’s ridiculous to be so sensitive about the content of fiction. It’s not real. I mean, come on. It’s all just a lot of games.”

Mary twirled a strand of hair around her finger. “Oh . . . how does it go . . . We dream, it is good we are dreaming. It would hurt us, were we awake. But since it is playing, kill us. And—we are playing—shriek . . .”

“Couldn’t have said it better myself.”

“What would you do for me?” she asked.

I studied her, and she seemed perfectly serious. She was making an offer.

“Slay a dragon. Ten dragons. Anything,” I said.

She smiled. “I’m glad you’re playing along. It’s a good sign.”

“It is? Okay. By the way, what exactly is it we’re talking about?”

“Just be flexible,” she said. I seemed to have accepted some challenge. Only I had no idea what it was.

“I’ll keep that in mind. When do we start this thing?”

She drew closer. “Presently. Scared?”

“Me? No.”

The crazy thing is, I actually did have the jitters, just a little. Suddenly her hand was on my neck. The gesture was tender, which, coming from her, worried me even more. My hand covered hers—I was trying, I think, to get free.

“Ready?” she said. “Now—”

DR. LUSTUCRU

D

r. Lustucru’s wife was not particularly talkative. But he beheaded her anyway, thinking to himself that he could replace her head when he wished for her to speak.

r. Lustucru’s wife was not particularly talkative. But he beheaded her anyway, thinking to himself that he could replace her head when he wished for her to speak.

How long had the Doc been crazy? I don’t know. Quite some time, I guess. Don’t worry. He was only a general practitioner.

The beheading was done as cleanly as possible, and briskly tidied up. Afterwards Lustucru set both head and body aside in a bare room that the couple had hoped to use as a nursery. Then he went about his daily business as usual.

The Doc’s wife had been a good woman, so her body remained intact and she did not give off a smell of decay.

After a week or so old Lustucru got around to thinking that he missed his wife. No one to warm his slippers, etc. In the nursery he replaced his wife’s head, but of course it wouldn’t stay on just like that. He reached for a suture kit. No need. The body put its hands up and held the head on at the neck. The wife’s eyes blinked and the wife’s mouth spoke: “Do you think there will be another war? After the widespread damage of the Great War, it is very unlikely. Do you think there will be another war? After the widespread damage of the Great War, it is very unlikely. Do you think . . .” And so on.

Disturbed by this, the doctor tried to remove his wife’s head again. But the body was having none of it and hung on pretty grimly. What a mess. He was forced to leave her there, locked in the nursery, asking and answering the same question over and over again.

The next night she broke a window and escaped.

Lustucru then understood that he’d been bad to the woman. He lay awake long nights, dreading her return. What got him the most was the idea that her vengeance would be fast, that he would be suddenly dead without a moment in which to understand. With that in mind, he prepared no verbal defences of his behavior. Eventually his dread reached a peak he could live on. In fact, it came to sustain him, and it cured him of his craziness, a problem he hadn’t even known he’d had. After several months there was no sign of his horror beyond a heartbeat that was slightly faster than normal. His whole life, old Lustucru readied himself to hear from his wife again, to answer to her. But he never did.

Other books

The Elementalist (The Kothian Chronicles Book 1) by Andrew Wood

Tarik: Entry Level Warfare by K. A. Kerr

Immortal Craving: Immortal Heart by Magen McMinimy, Cynthia Shepp

Bella's Wolves by Stacey Espino

30 Days by Larsen, K

Twisted Winter by Catherine Butler

When We Danced on Water by Evan Fallenberg

A Strange and Ancient Name by Josepha Sherman

The Rise of the Fallen (The Angelic Wars Book 2) by Thompson, J.J.

Angel Incarnate: Second Sight by Linda Creel