My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong (10 page)

Read My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong Online

Authors: Tristan Bancks

âIt's okay. Leave it to Jacky-boy,' he says. He lights the final torch, climbs the tree house ladder and makes an announcement to our disgruntled theme park guests: âAttention please, Valuable Visitors! Welcome to our premier attraction, the one you've all been waiting for, the most dangerous and death-defying ride at Jack and Tom's FunLand â The Treeee House High Dive!'

Everybody stops and looks up at him. They do not look impressed. He climbs onto the handrail that runs around the edge of the wooden tree house platform, four metres

above ground level.

âWatch me demonstrate a daring leap into the toxic, sludge-filled abyss known as Tom's Swimming Pool!'

He positions his toes right on the edge of the handrail. Twenty-five kids look on. A couple cheer. Others mutter about how shallow the sludge in the pool looks.

Jack closes his eyes, readies himself for the dive, flaming tiki torches all around. He lets go of the branch he is holding and leaps out over the pool fence. As he falls through the air, his foot kicks over one of the tiki torches. He executes a perfect belly flop into the bright-green cesspit, disappearing beneath the surface.

Kids gasp and gather around the pool fence.

âThat bloke's a nutter.'

âMaybe he split his guts open.'

âWhat if he's dead?'

The naked flame from the tiki torch sets

alight the crispy leaves of a dead vine hanging off the fence between Skroop's place and mine. Panic rises in my chest. It's never good advertising for a theme park when one of the owners dies on opening day, but I should also go and put out the fire.

Jack is still under, so I rip open the pool gate, climb the broken ladder, take off my T-shirt and scan the filthy swamp for any sign of life â only mosquitoes, thousands of them. I stand on the edge of the pool. I'm going to have to do this. I can smell smoke, but I figure Jack's slightly more important than the fence. I am poised to dive in when Jack bursts from the goop with a wild animal roar. He is the Creature from the Green Lagoon.

Kids cheer and queue up at the tree house ladder. Meanwhile, the small fire is quickly turning into a blaze.

âFire!' I scream as Jonah Flem launches himself into the pool. I am smacked in the

face by a thick gob of slime. Two more kids follow Jonah, flying out of the tree and into the pool.

âJack, put it out!' I shout.

Jack, waist-deep in muck, turns, sees the fire and tosses handfuls of green slime towards it, but he finds it hard to reach the flames. I throw him a broken plastic bucket and he scoops sludge from the pool's surface and hurls it at the fire. But then the weirdest thing happens: the flames explode. The green gunk is feeding the fire rather than fighting it. The flames surge higher than the fence and they start to spread along the fence line towards Skroop's house.

Jack throws another bucketful just as Skroop's head appears over the fence. He cops the entire bucket of goo in the face. Green stuff hangs from his brows and flames shoot up at him. Mr Fatterkins screams and leaps off his shoulder.

âFire!' Skroop shouts.

I run for the hose, twist on the tap and bolt towards Skroop. âOutta my way!'

He ducks and I give the flames the full force of the hose. The fire cringes. Kids in the pool scream âOver here!' and âWhat about this bit?' and âLet's get out of here'. I fight the fire for a full five minutes before bringing the blaze under control. By the time the last flame has been licked there is a large section of fence destroyed, creating a black, smouldering passage between Skroop's place and mine.

Kids look on. Jonah and Jack climb out of the pool. Others start to leave.

I turn off the tap and peer through the charred remains of the fence to check if Mr Skroop is okay. He walks towards me. He has ectoplasmic pool goop hanging from his eyebrows and mayonnaise in his ear. His clothes are soaking wet. His black hair dangles limply down his forehead.

âYou,'

he gasps.

I back up a little.

â

You

insignificant, flat-footed, jelly-back-boned, knock-kneed little prawn!'

âHuh?'

âTom Weekly?' says a voice.

I turn to the side gate to see a police officer walking slowly through my yard, surveying the destruction: torn Slip ân' Slide, smoking remnants of side fence, a bunch of swamp-creature kids escaping the yard as quickly as they can.

Pretty soon it's just me, the police officer and â

âIs Mr Skroop here?' the cop asks. âHe's made another complaint.'

Skroop steps through the gap in the fence. Mr Fatterkins is back on his shoulder, partly drowned, slightly charred.

âI am Walton Skroop,' he says, grabbing me by the scruff of the neck.

âI know who you are,' the cop says. He is a mountain of a man with a tree-trunk neck, who may have been a Viking in a previous life. âYou taught me in third grade. John Hategarden. You threw a piece of chalk at me, cracked the lens on my glasses.'

âOh, yes,' Skroop says. âWell, I'd love to chat but I have a crime to report. Thomas Weekly has been running an illegal business in a residential neighbourhood. He and his horrible little friends have assaulted me with mayonnaise, pool scum and water. They have set fire to my property

and

ruined Mr Fatterkins' nap time!'

Hategarden glares at Skroop. âDo you have anything to add to Mr Skroop's description of events, Mr Weekly?'

I look around at what used to be my backyard. I'm usually a genius in these situations, but I can't think of any way to deny Skroop's claims. He has me right where he

wants me. This grinds my teeth, churns my blood and gives my liver a Chinese burn. The best defence is good offence.

âIt's his fault!' I stab a finger at Dark Lord Skroop.

Skroop tightens his hold on the neck of my shirt.

âAnd how is that?' Hategarden asks.

I look down. I have to come up with something. âHe's trespassing!' I say, pointing to Skroop's tartan slippers, standing in our backyard.

âYou'll have to do better than that,' says the sergeant.

âHe swore at me!' I say.

âI did not!'

âHe called me an insignificant, flat-footed, jelly-back-boned, knock-kneed little prawn.'

âRight,' says Hategarden, making a note. âKnock-kneed, did you say?'

âYep.'

âWhat about the football?' I turn to see Jack crawling out from under the house.

âOh, yeah,' I say. âA couple of weeks ago, Mr Skroop chopped up my football and posted it into the letterbox.'

Hategarden stops writing and looks Skroop in the eye. âIs that true?'

âThe little scumbags should keep their sporting equipment in their own yard.' He scowls.

âAnd the scab,' Jack whispers.

âOh, yeah. And, once, he ate my scab.'

Hategarden tilts his head to the side, as though he mustn't have heard correctly.

â

My

scab,' Jack says.

âYeah, Jack's scab, but it was in my pocket. I was going to add it to my collection.'

âIs this true?' asks the sergeant. âDid you honestly eat a child's scab?'

âWell, I â'

âMr Skroop, you can't blame a bunch of

kids for setting up a business in their own backyard. I remember you being miserable, but to call a kid a knock-kneed prawn, to chop up his football and â' Hategarden gags, as though he might be sick ââ to eat a boy's

scab

, well, that is unforgiveable, un-Australian and possibly illegal.'

âIn my defence,' Skroop wheezes, âthe scab was quite small.'

Hategarden grabs him by the arm. âI think you'd better come down to the station and answer a few questions.'

âHe destroyed my personal property,' Skroop whines. âYou'll pay for this, Weekly!'

âSave the Scooby-Doo routine for your statement,' the sergeant tells him and, with that, he leads Skroop out the side gate and down the driveway to the police car waiting in the street. He opens the back door and Skroop climbs in.

âNo cats in the vehicle!' says Hategarden.

Skroop kisses Fatterkins on the nose and releases him on my front lawn.

A moment later the police car moves off up the street.

âWow,' Jack says. âThat was cool.' He pulls a handful of change out of his pocket, counts out eleven dollars and fifteen cents for me and eleven dollars twenty for himself.

âWhy do you get the extra five cents?' I ask.

âI came up with the idea.'

âNo, you didn't.'

âYes, I did.'

âNo, you didn't.'

âYes, I did.'

Jack heads out the gate and peels the FunLand list of attractions off the fence. He looks back at me, at what was once my backyard, just as Mum's car pulls into the driveway.

âYou wanna do it again next Saturday?' Jack asks.

âAre you kidding?' I ask, closing the gate. âDefinitely.'

âTom?' Mum snarls, popping her car door.

âIf I'm alive,' I add.

Jack vanishes.

So our arcade didn't turn out quite as well as we hoped, but don't let that put you off. It's an awesome idea and hopefully you learned a few lessons from our mistakes.

My Mistakes

- Don't go into business with Jack.

- Don't even become friends with someone like Jack unless you want your life to be a disaster.

- Don't offer your sister's toys as prizes because she will bash you. (Unless she's a younger sister, then that's okay.)

If you were going to create your own backyard theme park, what rides would you offer? How much would you charge? What would the food be like? (I recommend Scotch Fingers and Snakes, but buy heaps of packets.)

Â

Email your backyard theme park ideas and drawings and I'll blog them. I'm at: [email protected]

I think I hate my dog.

I know it's a bad thing to say. I don't mean to hate Bando. He's a Labrador, so he's nice and everything. In fact, he's maybe the best dog in the world, ever.

But I still hate him.

Look at him over there, lying on his back in the middle of my bedroom floor in a puddle of early morning sun, paws in the air, half-asleep, waiting for his breakfast to be served. He doesn't have a care in the world.

Me? I've got to get up, go to school, hang out with my annoying friend Jack, do chores

around the house, eat Mum's cooking, do homework, go to bed at eight-thirty. My life stinks.

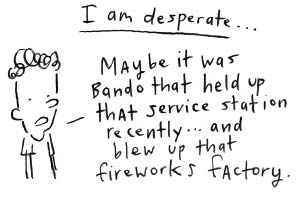

And you know what the most annoying thing is? I get blamed for everything that goes wrong around here. The other day Mum's laptop screen was smashed, and you know who she pointed the finger at? Me.

I mean, sure, I did it, but I didn't even get a fair trial. I tried to tell Mum it was Bando, but

she didn't believe me for a second. No-one would believe that the perfect dog could do anything wrong. I've had a gutful of it.

That's why I've devised my Ingenious Plan. I'm going to frame Bando for a crime. He'll get caught in the act and then he can start taking the blame for some of the weird stuff that goes wrong around here.

âC'mon boy!' I whisper.

I push myself up out of bed, tiptoe into the hall, past Mum's bedroom door and into the lounge room. The curtains are closed. In the dim light I can see a ceramic bowl sitting on a waist-high, white chest of drawers next to the couch. Man, that bowl is ugly. Poo-brown on the outside, yellow and green on the inside. Mum's favourite. I think she might have bought it from a garage sale, but she acts like it's a priceless antique. I agree that it's priceless, but only because nobody would pay anything for it.

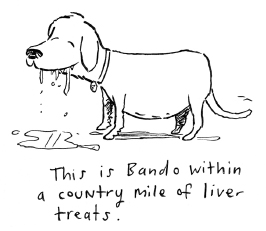

âStay,' I whisper to Bando. I creep through the lounge room and across the cold kitchen tiles to the cupboard under the sink where the dog stuff is kept. I grab the packet of liver treats and tiptoe back to Bando in the lounge room. His tail whirls like a helicopter blade.

âGood boy. Staaayyy.' I think I hear a noise. I listen for Mum. I do not breathe for thirty seconds or more before I decide that it was nothing.

I slide the ugly bowl to the corner of the chest of drawers. I make a show of sprinkling the treats inside. Bando watches carefully. A long thread of saliva droops from his mouth onto the floorboards.

âStaaaayyy,' I whisper. I move the bowl to the very corner of the chest of drawers, and I step back slowly towards my escape route.

âOkay ⦠Go!' I whisper sharply.

Bando runs on the spot, Scooby-Doo style, his claws desperately trying to grip

the slippery floor. He finds his footing and gallops towards the bowl, skidding to a stop and bumping into the drawers. They are too high for him. He reaches up to put his paws on the edge. He bumps the bowl, just as I had planned. It starts to fall, slo-mo, towards the ground. It spins and twists through the air. I begin to worry that the bowl might not break, but, in that instant, gravity does its thing and â

bam!

â it hits the floor, exploding, sending pieces flying everywhere. Millions of them. Under the couch, onto the rug, even into the kitchen. Bando starts to devour the treats.

My body zings with the thrill of the crime, and I feel an urge to sprinkle liver treats into some of the other ugly ornaments around the house. I want to fill the heads of my sister's

creepy porcelain dolls with them. I want to scatter them through her socks and undies basket where she keeps her diary.

But I don't.

I drop the bag of treats into a drawer, gently close it and tiptoe across the lounge room, down the hall and into my room, careful not to tread on any jagged pieces of bowl. I ease myself onto the bed and shove my headphones in like I've been listening to music the whole time.

I. Am. A genius.

Life will be better for me after this. Bando will start taking some of the heat, and I won't have to spend the rest of my childhood wishing I was a dog.

I wait.

I listen.

I wait some more.

I do not hear footsteps.

I take out one of my headphone earbuds.

Nothing.

Tanya, my sister, is at swimming, but Mum should have heard it.

I tiptoe across to the door of my room and peek down the hall.

Bando is still scouring the wreckage of the bowl, sniffing madly for more treats. I glide up to Mum's bedroom door, open it a few centimetres and peer in.

Asleep.

How could she be asleep? It sounded like a bomb exploding. What does it take to make your mother angry around here?

I go to her bedside and see that she's wearing earplugs. Garbage bin day. She does this on Tuesday mornings so that she doesn't wake up at five-thirty.

âMum,' I say quietly.

Nothing.

âMum,' I say a little louder.

All I can hear is Bando sniffing and tap-

dancing around in the lounge room. It's really starting to get on my nerves.

I pluck out an earplug. âMUM!'

She sits upright and says, âWhaâ, whaâ', like she's woken from a nightmare. But, really, she has woken into one.

âSorry,' I say. âBando. He knocked over your favourite bowl.'

âWhat?' she asks again.

âHe kind of went mad and knocked into the drawers, and he just ⦠smashed it. Come see.'

She groans loudly, puts on her slippers and follows me out.

âSee?' I say, pointing to the scene of the crime.

âOh, Tom, what happened?' she says.

Bando has disappeared, which is not helpful to my case.

âWell, he was just ⦠he ran through and jumped up, and it just â¦'

âWhy would he do that?' she asks, picking up a large piece of the horrible bowl and turning it over in her fingers.

âLike I said, he just kind of went mad. I guess he's getting old and weird,' I say.

She kneels down and picks up another piece, examining it closely.

âMaybe it was him who broke the laptop, too?' I suggest.

She glares at me and I know I've made my move too early.

âWhere were you when this happened?' she demands.

âIn my room.'

âDoing what?'

âListening to music. With headphones on.'

âAt this time of the morning?'

âMm-hm.' I nod.

âAnd you didn't hear it?'

âNope.'

âSo how do you know it was Bando, and how do you know he just “ran through and jumped up”?' she asks.

âWell â¦' I say. How can she roll out of bed and be like a forensic scientist seconds later? I have to tread very carefully here.

âBecause he was still here when I came out,' I say, âright in the middle of the wreckage.'

Bando comes to the lounge room doorway from the kitchen, panting loudly, smiling his goofy, black-lipped smile.

âBad boy!' Mum says. âSit!'

Bando drops, rests his chin on the floor, looking guilty. I feel kind of bad. But only kind of.

âI think we should sell the dog,' Mum says, glaring at him.

I laugh. I know she's joking but it's still nice to hear.

âGo and get me the vacuum cleaner.'

âYes, Mum.'

I head off down the hall, not skipping but close. I think she's buying the story, which means that, in one slick and cunning move, I have framed Bando and destroyed the ugliest bowl in the history of ceramics. I wrestle the vacuum cleaner out of the cupboard and head back up the hall.

Mum is kneeling on the floorboards, scraping the pieces together with her hands. Tiny fragments fall into the cracks between the boards. I plunk the vacuum down next to her.

âThanks,' she says quietly, sniffling.

âAre you okay?' I ask.

Bando gets up and snorts through the

broken bits again.

Mum wipes her nose. âI remember the man I bought this bowl from,' she says. âA little old guy at the market in Marrakesh in Morocco when I was backpacking. Looked like he was a hundred years old. He made this for his wife who'd died, and he said that he wanted me to have it.'

âReally?' I ask. âI thought you got it from a garage sale down the street.'

âHe said my eyes reminded him of hers. Didn't even want me to pay for it, but I did. Can you plug this in?' She hands me the cord and I drag it across the lounge room to the power point. I can feel a little lump in my throat. I didn't know any of this.

Bando is sniffing around the drawers where I put the treats.

âBando! Outside!' I plug the power cord in.

âTom ⦠What's this?' Mum says. She picks up a small, dark-brown piece from the floor

and inspects it. âThis doesn't look like my bowl.'

âHuh?'

She pokes her finger at a gooey residue on the piece and rubs her fingers together. âSaliva.' She sniffs it. âIt smells like tuna.' She sniffs again. âNo, more like ⦠liver.'

I swallow so hard I almost swallow my lips.

âWhy on earth would there be a liver treat in among the broken pieces of my bowl?' she asks, turning to me.

Bando is really sniffing that drawer like mad now.

I shrug. âI wasn't there. Maybe â¦'

âShow me your headphones.'

âWhat do you mean?'

âShow me.' She grabs my headphones out of my hand. She snaps on the lamp that sits on top of the drawers where the bowl once sat. She holds one of the earbuds up to the light.

âHmm,' she says.

âWhat?'

âInteresting.'

I can feel the heat of the lamp. I undo the top button of my pyjamas. It feels kind of warm in here.

She wipes her pointer finger over the earbud and then studies her fingertip, close to the naked bulb of the lamp. She almost looks professional.

Even with my top button undone I'm burning up. I wipe away the sweat trickling down my temple.

Mum dusts her fingers on her dressing-gown and stands. I have never noticed how tall she is before. She towers over me. I can

see right up her nostrils. They are wide and horse-like. She is an angry horse-detective.

âDid you have anything to do with this, Tom?' she asks, looking into my eyes.