My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong (5 page)

Read My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong Online

Authors: Tristan Bancks

Nan hands me a small, paper-wrapped package. âPlan B,' she says.

âBut â'

âDo it!' she tells me.

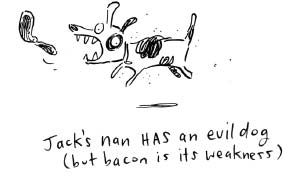

So I do the thing we planned, even though I know it's wrong. I creep up behind the cart, careful not to be seen in Sue's rear-view mirror, but the dog barks like mad. I unwrap the package to reveal half a kilo of bacon strips, and saliva drips from the dog's angry, barking jaws.

I try to stuff one of the strips into the chunky tyre tread as the wheels turn, but I almost burn the tips of my fingers off. I try again and manage to jam one strip of bacon in. Then two, three, four, five strips before the dog launches itself off the cart, barking midair, ready to finish me.

I stop, drop and roll away from the vehicle, down the hill. The dog hits the ground and I wait for it to maul me, to gobble me up like a strip of free-range bacon. But, instead, Nan's plan begins to work. The dog turns to the cart and bites one of the tyres in an attempt to get at the bacon. It howls in pain but then tries to bite the tyre again.

âWhat are you doing?' Sue screams at the possessed dog.

It nips and barks and bites until it is almost sucked up by the turning wheel. Then there is a hissing sound from the tyre, and the cart leans dangerously to the right.

Further down the hill, my nan wheezes: âTake that!'

âThat's not fair!' Jack yells.

Click-clack-click-clack-click-clack.

Nan catches up to Sue just as we hit the final steep section of hill. The last ten metres. Sweat storms down her forehead and sunken cheeks.

âCan't I take your jacket, Nan?'

âNo, I'm fine,' she says, slurring her words. She shuffles forward, then falls. I reach out to catch her, but I miss and her head goes conk on the road.

âNan!' I slip an arm beneath her and rest her head in my lap.

âThanks, love,' she says groggily. âFeeling a bit woozy. You know, I didn't realise Everest would be this hard. We must be above 8000 metres. Have you got the oxygen?'

I unzip her enormous ski jacket and roll her out. âIt's okay, Nan. The race is over. We're throwing in the towel.'

âBut Everest,' she says. âI have to get to the top. I have to beat that vile woman. I have to be the oldest â¦'

âForget Everest,' I say, looking up at the cemetery gates just ahead. âIt's over.' Looking down the hill, I see Sue's cart several metres behind us, not moving at all now.

âHelp me down!' Sue snaps at Jack.

âBut â'

âNo buts.'

Jack pushes and shoves and squeezes his enormous grandmother off the cart. She staggers and falls awkwardly to the road. âHelp me up, you twit of a boy!'

âI'm trying!' he says. But Jack cannot budge her, no matter what he does. So Sue begins to crawl up the hill, groaning and scraping her way towards the top. Soon she is four metres behind us. Then three. Then two. She is like a maimed rhinoceros, inching her way along. I start to worry that she is going to roll right

over us, mash us into the bitumen like road kill.

âOh, no you don't,' Nan says, catching sight of Sue. Nan pushes herself up and out of my arms, clutching the flag in her bleeding fist. I try to hold onto her but she slaps at my hand and starts to crawl up the steepest section of Cemetery Hill.

âI'm going for the summit,' she says. âRadio back to base camp. Let 'em know.'

I laugh at her joke. Then I realise that it isn't a joke. I want to stop her, but I also don't want to take away her moment of glory.

Sue crawls past me, so close I can smell her sweaty armpits and coffee breath. She is right on Nan's tail. Nan doesn't have a hope.

Sue reaches out a hand, glistening with sweat, and grabs Nan's pearl necklace, pulling on it like reins to drag her back.

Nan makes a choking sound and Sue crawls forward.

âGo, Nan!' Jack shouts.

Sue heaves on the necklace once more and the pearls explode from around Nan's neck and bounce onto the road, rolling downhill. Nan will not be pleased. Those pearls were given to her by her own mother, Hepzibah Worboys, my great-grandmother.

Sue's hands land on a bunch of pearls, then the pearls roll beneath her knees and she scrambles and slips and squawks. Pretty soon, she's rolling back downhill on an avalanche of pearls.

âHelp!' Sue screams, trying in vain to get a grip on the road. Jack and the dog look up and attempt to leap out of the way â but too late. They are pinned to the front of the cart by Sue's gargantuan body.

At that moment Nan claws her way through the cemetery gates, plants her flag and falls flat to the ground. Hunched gargoyles look down at her as the first rays of golden light touch her face.

âI've done it, Tom! I've done it,' she calls out triumphantly.

âYes, Nan.' I smile and bend down next to her. âYou've done it.' I stroke her face, wiping some of the blood from her forehead. I can't believe it's over. My crazy grandmother thinks she has climbed Mt Everest.

âThanks for training me, Tommy.'

âThat's okay, Nan.'

âJust think. In three months' time, I'll be doing the real thing. I'll be on top of the world!'

âEwww, you've got poo on your back,' says a small voice behind me.

I turn to see a little punk with wingnut ears and a galaxy of freckles. He is staring at me.

âNo, I don't,' I say.

âYes, you do.'

âIt's not poo. It's my birthmark.'

âWhat's a birthmark?' the kid asks.

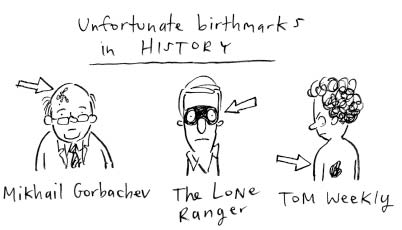

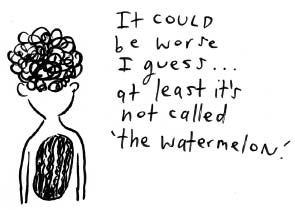

Every year I dread it â the school swimming carnival. You're not allowed to wear a rash vest in races. That means my dirty, no-good, big brown birthmark in the middle of

my back (which my best friend Jack calls The Fig) is on parade for the whole school to see. The kid with the wingnut ears looks like he's in Year Two. He's lining up behind me at the dive blocks, waiting for his final race.

âA birthmark,' I explain through clenched teeth, âis a mark that you have from when you are born. Sorry if that's confusing for you.'

âDid the stork do a poo on you?' the kid asks.

The little girl next to him laughs. I do not. I want to pick him up and throw him into the deep end. Instead, I lean in real close.

âDid the stork do a poo on your face?' I ask.

The kid's smile drops. He looks at me. His bottom lip quivers. He looks like he's about to start bawling. I look around, worried that a teacher is going to see. Then he stabs a finger at me and shouts, âHey, everybody! Look at his back!'

Every kid and teacher within a thirty-metre radius, including the swimmers on the blocks about to dive in, looks at me â thirty or forty people, staring. Now my lip starts to quiver and I look like

I'm

going to start bawling. The starter gun fires for the race but only three kids dive in. The other five are trying to get a good view of my back.

I stomp on Wingnut's toe.

âOwwwwwww!'

I cover The Fig with my hand and make a beeline for the change rooms, marching all the way down the side of the Olympic pool. I can feel the crimson-red embarrassment of the kids watching and pointing and laughing. It's the longest walk of my life, and when I reach the change rooms I want to cry.

It is empty and the pale-blue concrete makes the place feel cold. I stand in front of one of the basins. I reveal The Fig and turn to look at it in the dirty, soap-smeared mirror.

âI hate you!' I whisper to it. âYou filthy, good-for-nothing swine. I'd probably be a swimming champion if it weren't for you. I wish you were gone forever.'

I head into a toilet cubicle, slam the door, flip down the seat and slump onto it, head in my hands. In that moment I decide I will never go swimming again, never leave the house again, until I have had an operation to slice that thing off. In the distance I hear the starter gun go for the next race â my race.

âHello, Old Thing,' says a faraway voice.

I bend down to look under the toilet cubicle door, but I can't see any feet.

âNo, no, up here!'

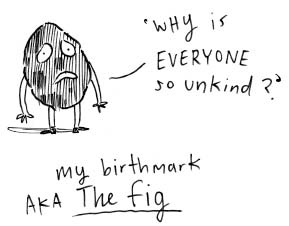

I stand and turn to see a small animal perched on top of the toilet, right next to the flush button. It is chocolate-brown with a few black patches, two tired little eyes and a sad mouth. It looks like an oval-shaped cookie with tiny arms and legs.

âRather nice to get a good look at your face, finally,' it says. âI had the impression that you might be ugly, but you're a handsome young man.'

I stare at the thing. If I didn't know any better, I would say it looks a little bit like The Fig.

A lot

like it.

âAnyway,' it goes on, âI just wanted to say that there's no need to hate me. It must be difficult for you at times, having a large birthmark like me, but you and I are blood brothers. Together forever.' It gives me a wink. âTo hate me would be to hate yourself, and that would be just plain silly.'

âWho are you?' I ask. âWhat are you?'

He looks at me like I am stupid. âI think you know.'

I reach around and my fingertips touch the skin in the middle of my back. It is smooth. No lumps, no bumps. It feels good.

âWhat do you want from me?' I ask.

âNothing, Old Chap. I just want to reach out to you, to let you know that I feel your pain. I heard what that horrible child said to you out there and I, too, wanted to throw him in the deep end.'

You read my thoughts?

I wonder.

âOf course,' it says in response. âI think what you think. I feel what you feel. We are one and the same.'

Not anymore

, I think to myself.

âI heard that,' he says.

I try not to think anything.

âAnyway, I just wanted to let you know that I'm watching your back, okay? Hug?' It stands on tippy-toes and holds out its little Fig arms, but I so don't want to hug it.

I run my fingers over the smooth skin of my back again and it feels so good. I know what I have to do.

I unlatch the door behind me.

âWhere are you going?' The Fig asks, its sad little mouth turning down at the edges.

I hear footsteps and kids' voices coming, so I lock the door again.

âPlease, don't leave me!' it cries. âYou weren't going to abandon me, were you?

I was only trying to help. I've made a terrible mistake. I'll die. I need food.'

âQuiet,' I whisper. âWhat do you eat, anyway?'

âWhatever you eat,' it says. âAnd on that note, if you could steer clear of bread, that would be marvellous. I'm thinking of going gluten-free.'

âWho are you talking to in there?' a voice asks from the other side of the toilet door. It's Jack. There are lots of other voices in the change room now, too.

âNo-one,' I say. âLeave us alone.'

âWho's “us”?' Jack asks.

I look at The Fig, my lifelong shame. I could unlock that door and walk away now, but I need to make sure it never finds me. I won't sleep at night knowing that The Fig is out there. And if it can read my thoughts, it'll know where I am.

âAre you okay?' Jack asks. âThat was pretty

brutal out there, but no-one's talking about it anymore. It's the last race. Just come out. Wear a T-shirt.'

âGive me a minute,' I say, reaching around to grab the toilet brush. I poke The Fig with it and it dances out of the way. I stab again and it hops to the side, hiding behind the half-flush button. You might think a Fig would be frail or sluggish, but this thing is agile and quick, in peak physical condition. I swing the toilet brush sideways, determined to whack him, but he leaps over it easily, doing a forward somersault and landing on his feet again.

âHelp!' The Fig shouts.

âHelp who? What are you doing in there?' Jack asks.

I look The Fig right in the eye. He is standing on top of the flush button. There is no way that thing is ever touching me again. I will finish him now. I move in with the brush raised like a lightsaber. I bring it down

hard and fast, but The Fig dodges out of the way. I take another swipe but he ducks. Then I go

chop-chop-chop

with three fast little whacks, but he weaves. He pauses in a half-crouch, reading my next move before I even make it.

I try not to think. My gut takes over. I take one last swipe at The Fig and I make contact. It overbalances and falls into the toilet, just managing to hang on to the edge of the seat with one tiny hand. It's looking up at me, scared out of its mind.

âHelp. Please!' it begs.

I rest one finger on the button.

âPlease,' The Fig pleads. âDon't flush.'

All I have to do is poke his tiny Fig-fingers with the brush, press that button and it will be gone. My shame will be no more. As I press down lightly on the button and the water begins to churn he looks into me, and I can't help feeling a connection. I can feel the panic inside him. It's like I'm looking into my own

eyes, like I'm flushing myself.

His fingers start to slip from the toilet seat and, without thinking, I reach for his hand ⦠but it's too late. He goes under the water and I panic.

His head emerges and he takes an almighty breath. âCan't ⦠swim, Old Chap!' he wheezes before the water swallows him again. This is horrific.

There are voices and footsteps outside, kids coming into the change room.

The Fig is down for a few more seconds before he resurfaces, thrusting a desperate hand up towards me. I reach into the grimy

bowl, grab him, careful not to crush his cookie-thin body, and I haul him to safety.

There are lots of kids in the change room now, some in cubicles either side of me.

Jack knocks. âCarnival's over. Let's go, man.'

I take deep breaths. I slowly open my dripping hand to look at The Fig, expecting to see his thankful little smile. But, instead, I find him crouched and angry. He growls and launches himself upwards. I try to catch him midair with my left hand, but he's too quick.

Slap

. He attaches himself to my face. I try to peel him off but he won't budge.

âWhat are you doing?' I ask, but he doesn't respond. âI saved you!'

Nothing.

Another kid knocks on the door of my cubicle.

I scratch at my right cheek, trying to lift the edge of The Fig. I run my fingers over its rough surface. But it is stuck hard.

A head pokes over the wall from the next toilet cubicle. âWhat's goin' on, Weekly? People need to go to the toilet.' I look up. It's Brent Bunder, the biggest kid in our year. âErrr. What's on your face?'

I cover my cheek where my dirty-no-good-big-brown-birthmark is. I unlock the door and head out, slamming straight into Jack.

âWhat's up?' he asks.

âHey, it's the kid with the poo on his back!' says Wingnut, the pipsqueak who started all this.

âIt's

not

poo!' I scream. âIt's my birthmark. See!'

I rip my hand away from my cheek, showing everybody. Forty boys fall silent and stare. A couple in the back start to giggle.

âIs that funny? You wanna laugh at the kid with The Fig on his face? You want a piece of me?

Do ya?

'

Some of the boys look scared now.

âI was born with it and I'm

stuck

with it, all right?'

Kids shift uncomfortably. A couple turn away.