My Life So Far (29 page)

Vadim and me looking around the fixer-upper farm we bought outside of Paris, 1966.

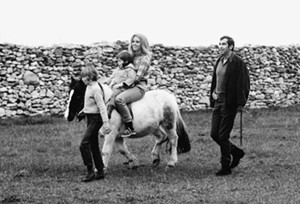

Nathalie leading her pony, Gamin, with Christian and me riding and Vadim following. That’s the stone wall I built behind us.

(© David Hurn/Magnum Photos)

The hamlet of Saint-Ouen-Marchefroy was a ten-minute walk from the house, and I liked to stroll in at midday when folks were taking a break from their work, to get a sense of who my neighbors were. They had no idea that I was a movie star, and though I never asked, they probably wouldn’t have known who Vadim was, either. I became friends with one woman who lived in the farm closest to ours. She liked to give me fruit tarts she’d bake. When I’d visit her, she was always at her sink or stove, and because her hands were wet or greasy, she’d bend her hand back and give me her wrist to shake, a gesture I encountered more than once in that hamlet, the shake of a farmer’s wife. (I never got to use it in a movie, alas.) I enjoyed sharing such moments with my neighbors. I would sit in her kitchen, drinking her strong coffee and thinking how lucky I was; my friends back home would not likely get to do this.

Reluctantly I went to Hollywood for several months to make

Any Wednesday.

While there, I decided Vadim and I should get married—at least I think it was my idea. Like buying the farm, I felt marriage would make our commitment deeper, bring normalcy into our relationship, and be better for Nathalie. I think I also wanted to prove I could make it work and pull off something at which Dad had failed.

We arranged for a secret wedding in Las Vegas. Vadim flew up first to get the license. Then, after filming on a Friday, I flew up with my brother and his then wife, Susan; Brooke Hayward and Dennis Hopper; friend and journalist Oriana Fallaci (who was sworn not to write about it); Vadim’s mother, Propi; and his best friend, Christian Marquand, with his wife, Tina Aumont. As the plane circled over Los Angeles, we looked down to see Watts in flames, an omen, though I didn’t see it as such at the time.

The ceremony took place in our suite at the Dunes Hotel. The minister was disappointed that we’d forgotten to buy rings, claiming that reference to rings was the best part of his speech. So Christian lent Vadim his ring and Tina lent me hers; it was much too large for my skinny finger. I had to hold my finger upright throughout the ceremony, which created the impression that I was giving the whole proceeding the finger. The fact is, however, that I cried when we were pronounced man and wife. We had been together for three years, but I hadn’t realized how much formalizing our relationship would mean to me.

After the ceremony, some in our small group began enthusiastically renewing their relationship to Chivas Regal, and by the time we got to dinner, things were starting to feel sad. We ate in a cocktail lounge, where a long buffet table with a massive glass swan sculpture separated us from a stage on which a striptease version of the French Revolution was being performed. We watched as a topless woman was “beheaded” on a guillotine to the strains of Ravel’s

Bolero.

I told Vadim I thought we should adjourn to our room. But Vadim disappeared into the casino and I ended up sharing a bed with his mother. I really was ignorant of the realities of compulsive gambling, but it wouldn’t have mattered. I was hurt and angry, and as we flew back to Los Angeles the next afternoon, I remember thinking, What have I done? But, like I say, I’d learned to compartmentalize—bury the hurt and move on.

The following year we filmed

La Curée

(

The Game Is Over

), our second film together, and again it was a happy experience for us both. Sharing a common goal, joining in a structured workday, gave sense to our union that often seemed to be lacking outside of work. During the filming of

La Curée,

I received a letter from the Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis asking me to play the title role in

Barbarella,

based on a French comic strip by Jean-Claude Forest. Brigitte Bardot and Sophia Loren had both been offered the role and turned it down, and this was my inclination as well. But Vadim was adamant that science fiction films would be the wave of the future, that this could be a terrific sci-fi comedy, that I should do it, and that he should direct.

Vadim had long been an aficionado of science fiction, and the added whimsy and sexiness of the story clearly played to his strengths. His passion for the idea convinced me to go along. As soon as

La Curée

wrapped, he began working on the script for

Barbarella

with satirist Terry Southern. Meanwhile, I returned to the United States to do the film

Hurry Sundown

with Otto Preminger, Michael Caine, Burgess Meredith, Beah Richards, Faye Dunaway, Robert Hooks, Diahann Carroll, Rex Ingram, Madeleine Sherwood, and John Phillip Law. It was shot in and around Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and while it was ultimately not very good, for me the experience was profound.

The entire cast, black and white alike, was housed in a motel in Baton Rouge, a small city about seventy-six miles from New Orleans. The motel had never been integrated before, and the first night we arrived, a cross was burned on the motel lawn. All the rooms opened onto a swimming pool, and the day Robert Hooks dove into that pool for the first time, locals peered from around corners as though they expected the pool to turn black. I was sure the reverberations were heard all the way to New Orleans. Diahann Carroll told me how concerned she was because as a black woman from New York, she’d forgotten how to behave “down here in Klan country.” She worried that without thinking she’d do something that would be normal for her up north but dangerous down here.

One day we were filming in the small county seat of St. Francisville, in front of the courthouse, when I looked down to see a cute little black boy of about eight shyly watching the filming. I squatted down to talk to him and then, as I was being called back into the scene, I leaned over and gave him a kiss.

Snap!—

someone took a picture of the kiss, and it appeared on the front page of the local paper the next day.

All hell broke loose. Shots were fired into the production wagons, and threatening phone calls were made to the production office about what would happen to us “nigger lovers” if we didn’t get out of town—which we did. I was shocked. I hadn’t realized what little progress toward desegregation had been made. I’d been to an SNCC fund-raiser and had seen Watts in flames, but I hadn’t been paying enough attention. I was still using the term

Negro

while the African-Americans in the cast were calling themselves “black.” I listened to conversations between Robert Hooks, Beah Richards, and others following the shooting incident: about a burgeoning “black nationalism”; about Stokely Carmichael calling for “black power”; about a growing sense that blacks had only themselves to depend on. I kept my mouth shut but was disturbed and hurt—poor little me, a white do-gooder, just beginning to feel I could get involved and now being told I wouldn’t be wanted by the new black movement they were describing.

For answers, I turned to a white cast member, Madeleine Sherwood. She was a close friend from the Actors Studio, and she’d been in

Invitation to a March

with me. Her longtime partner was black, and she had tried to get me involved in supporting the Freedom Rides. I’d gone to Big Sur instead. Madeleine helped me understand that in the years since I’d been living outside the United States, there had been a sea change in the civil rights movement. The nonviolent strategy that had been its foundation was based on the assumption that there was a latent conscience in America that, when appealed to, would step up and put an end to segregation. What had become apparent to blacks and to white civil rights workers alike was that neither the segregationist South nor the northern white liberal establishment was ready to integrate. Yes, laws had changed. But the new laws did little to alter the segregationists’ pathological hatred of integration. The liberal establishment, with some exceptions, seemed to support the movement but refrained from taking strong enough action either to protect civil rights workers from violence or to uphold the law. Apparently the Democratic Party had been too dependent on racist Dixiecrats to dare to rock the boat seriously. But too much had happened and too much blood had been shed for the activists to settle for liberal tokenism. What was the good of new laws if the dismal reality of black lives didn’t change? Blacks read the lack of decisive action as a signal that they had to go it alone. Hope had turned to cynicism. Peaceful protest was starting to look less viable than violent action.

I realized that I, who had sat out these turbulent years, never coming close to experiencing what black Americans endured, was in no position to judge the rise of black nationalism, though it was hard for me to comprehend how any group could achieve anything positive through separatism and violence. I thought of my father and his childhood story of the Omaha lynching, and of his hero, Abraham Lincoln—and I wondered how, in this democratic country of ours, we could have made so little real progress.

Vadim was able to visit only for a week or so during the shooting, because he was involved in preparations for

Barbarella.

But during his brief stay, while sitting around the motel pool, he saw the lean, tanned, blue-eyed John Phillip Law emerge from the water like a piece of sculpture—and he decided then and there that he was the one to play

Barbarella

’s Pygar, the blind angel who recovers his will to fly after he and Barbarella make love.

From

Hurry Sundown

I went almost immediately into

Barefoot in the Park,

which would turn out to be my first genuine hit—finally. How I ever survived so many bad films, I’ll never know! Charles Bluhdorn, chairman and CEO of Gulf + Western, had just purchased Paramount Pictures, starting what became a wave of corporate buy-ups that would take American moviemaking out of the hands of impassioned, visionary individuals like Irving Thalberg, Jack Warner, Samuel Goldwyn, Harry Cohn, and Louis B. Mayer and turn the studios into corporate subsidiaries. I was informed that Bluhdorn had threatened to throw himself out of his New York skyscraper if I was cast in the female lead. I don’t know why or what changed his mind, but once filming started we got along fine. I was very happy to be working with Bob Redford again and looking forward to our cuddling-in-the-cold-apartment scenes, something I hadn’t gotten a chance to do in

The Chase.

There’s something about Bob that’s impossible not to fall in love with. We’ve made three films together, and each time I was smitten, utterly twitter-pated, couldn’t wait to get to work, wouldn’t even get mad when he was his habitual one to two hours late. He never knew it, of course. Nothing ever happened between us except that we always had a good time working together. I remember the first day he and I showed up in the Paramount administration building. As we walked down the corridors, secretaries stuck their heads out their office doors to watch him go by.

Ah,

I thought,

he’s going to be a star.

But one of the things I love about him is that instead of puffing up his ego, this made him uncomfortable. I have never seen women react to a man the way they do to Bob: In Las Vegas once, when we were filming

The Electric Horseman,

a woman threw herself on the ground at his feet. He seems to want to disappear at times like this.

Of all the male stars I’ve worked with in my fifty films, Bob is the only one about whom women ask me, “What’s it like to kiss him?” The answer I always give is, “Fabulous.” The reality is a little different: fabulous for me, not so fabulous for him. He hates filming love scenes. He seems to want to get them over with as soon as possible. Damn it! Fortunately he has a sense of humor about this, and about most everything. Actually, he’s a stitch. Besides his male attractiveness, I find a Hepburnesque quality about Bob: You feel that he is somehow better than most other mortals. You

want

Bob to like you, so you are loath to do or say anything that might make him think less of you. This is not someone you would want to gossip about. Maybe this is why, in a town known for gossip, no one tries to get into his business.