My Life So Far (30 page)

In between scenes on

Barefoot in the Park,

we shared stories about growing up in West Los Angeles in the forties, about living in Europe—where he’d also gone to study painting in the fifties (only

he

actually painted)—and about our shared love of horses. But mostly I remember Bob describing with great passion a piece of property he had bought outside of Provo, Utah, the home state of his then wife, Lola. They had designed an A-frame house that they had just built on the property, and Bob was full of excitement about the construction. Little did either of us imagine then that this property with its little A-frame would become first the Sundance ski resort (where my son, Troy, learned to ski) and later the Sundance Institute, which has made such significant contributions to independent filmmaking.

Goofing off with Bob Redford between takes on

Barefoot in the Park.

(Photofest)

A scene in

Barefoot in the Park.

(Photofest)

Making

Barefoot

was a joy. First there was Bob; then we had that flawless script by Neil Simon; and Gene Saks was the perfect comedy director. Everyone in the cast was talented, nice, and fun to work with, especially Mildred Natwick, who’d been in children’s theater and then the University Players with my dad.

It’s not often that a comedy survives the passage of time, but I have seen

Barefoot in the Park

countless times and I find its appeal to be timeless. Bob’s, too.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

BARBARELLA

Hey! Nothing is what it seems.

—M

ADONNA

W

HEN FILMING ON

Barefoot

wrapped, Vadim and I moved to Rome, where

Barbarella

was to be shot at the De Laurentiis studio. We rented a house on the outskirts of the city—part castle, part dungeon. There was a tower next to our bedroom that dated from the second century

before

Christ. At night we regularly heard scuffling and mewing coming from there. One evening during a dinner party in the cavernous living room below, there was a loud noise, some plaster fell from the ceiling, and an owl fell onto Gore Vidal’s plate. It turns out that a family of large owls had been making the racket in the tower.

None of the special effects and optical techniques we take for granted today existed in 1967. Vadim and his collaborators had to invent everything, and sometimes the ideas worked and sometimes they didn’t. The opening title sequence shows Barbarella peeling off her “astronaut” suit as she floats topsy-turvy in her fur-lined space cabin. Much was made of this unusual scene, the first weightless striptease in movie history (and perhaps the last!). Claude Renoir, brilliant cinematographer and nephew of French film director Jean Renoir, came up with a way to film it while playing around in his hotel bathroom one evening. Here’s how it worked: The set of the space cabin, instead of sitting like a normal room that you could walk in and out of, was turned upward so that it faced the ceiling of the enormous sound stage. A pane of thick glass was laid across the opening of the set, and the camera was hung from the rafters directly above it. I would have to climb up a ladder and onto the glass, so that from the camera’s point of view the space cabin was behind me and I appeared to be suspended in space. Then I would begin slowly to remove my space outfit while a wind machine blew my hair and the discarded articles of clothing around as though they were floating with me in space. I was terrified that the glass would break; terrified of rolling around like that in the altogether; terrified of not being perfect. Once again, I just didn’t think I could say no. But Vadim promised that the letters in the film credits would be placed judiciously to cover what needed to be covered—and they were.

The biggest challenge for us was figuring out how to film the sequences where Pygar, the blind angel, flies through space carrying Barbarella in his arms. A remote control specialist devised a scheme: A huge rotating steel pole stuck out horizontally from a cycloramic gray screen. The pole had large hooks and screws at the end, on which two metal corsets were attached. One corset had been made to fit John Phillip Law and one was for me, and they were skintight because our costumes had to fit over the metal and not look bulky.

We got all suited up, first the cold metal corsets, then the costumes, and then John’s wings were strapped onto his back with wires running from the wings to a remote-control machine. Then a crane hoisted us up and we stood on the platform while John was hooked up to the end of the pole. Then my metal corset was screwed to the front of his, putting me into a position that made it look as though he were carrying me. After we had been suited up, hoisted up, and screwed up, the moment of truth arrived. The crane, which until then had been supporting us, was moved away, leaving us suspended in air, with the weight of our bodies jamming our hipbones and crotches into the metal corsets.

It was sheer, utter agony. And with all that, we had to remember our dialogue, look dreamy, and occasionally be funny. The muted sounds of misery I could hear from John (who was bearing the added weight of his wings) told me that his pain was worse than mine, and mine was nearly unbearable. No one had taken our poor crotches into consideration! John was convinced his sex life would be brought to a premature demise.

There we’d hang, while somewhere out in the darkened sound stage the technician worked the remote controls, making the pole rotate this way and that and making John’s wings flap up and down. While we hung there, rotating, a film of the sky with clouds moving past (shot from an airplane) was projected onto the gray screen behind us. Nothing of the sky and clouds could be seen on our faces or costumes, and you couldn’t even see what was being projected on the screen until the film had been developed. John and I weren’t actually moving forward through space, but the film was to make it appear that way. That was the intention. This type of front projection is common today, but back then it had never been done before—we were the guinea pigs. Lots of things had to work properly at the same time: The steel pole had to rotate in sync with the moving sky, the remote-control specialist had to make Pygar’s wings flap in the same way, and the projection onto the gray screen had to function properly. This all took days and days to rig up, while John and I hung there, our private parts growing progressively numb.

John Phillip Law as the blind angel Pygar carrying Barbarella. The agony doesn’t show.

(Carlo Bavagnoli/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

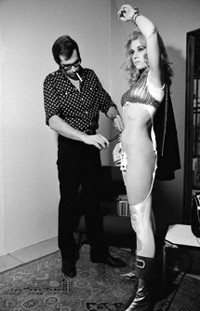

Vadim making sure all the rips are in the right places.

(© David Hurn/Magnum Photos)

Pygar approaching his nest, where we will make love and he will get back his will to fly.

(© David Hurn/Magnum Photos)

I will never forget the first day we finally had rushes to look at. Everyone was excited and anxious, since flying without the help of wires had never been done before and so much depended on the believability of the flying scenes. There was an entire aerial battle that was critical to the story. The lights in the screening room dimmed, the film began to roll and

.

.

.

Oh my God

.

.

.

we were flying backward!

It was too funny not to laugh: The one most obvious thing, what direction the clouds and landscape were moving, had been overlooked. But what was also apparent was that once they got us in sync with the background, it would work. It really did look like we were flying, like he was carrying me, like we weren’t in pain, like the clouds and mountains were passing by—just going the wrong way.