My Life So Far (37 page)

In time I would discover a new “family” of people whose lives seemed to be motivated by the desire to create a better world. It would be a motley crew: black radicals, a former Green Beret, human-rights lawyers, soldiers, Native Americans. I wasn’t always sure what they thought of me. But I wanted to learn from them and become someone who had my own narrative, my own direction.

They were, of course, all men.

S

hirlee recently told me that Dad was happy when I became a mother. “Maybe now she’ll see how hard it is to be a working parent,” he’d told her during the time I was living with them. He hoped this would help me forgive him his parental shortcomings—which I have, many times over.

But it wasn’t my being a “working parent” that caused me to be an inadequate mother. Had I been a stay-at-home mom, I might have been an even worse parent: I just didn’t have it to give. I wasn’t given it, I don’t think my parents were, and I wasn’t able to break that cycle of disconnect until later in my children’s lives. What I

did

manage to do was marry men who were good fathers and provide surrogate adult support systems to fill in the gaps. Breaking the cycle requires that there be

someone—

the other parent, a grandmother, a loving nanny, a surrogate parent—who consistently gives unconditional love to the child. A child with even a modicum of this kind of loving will be better equipped to be a good parent to her or his own child and thus break the cycle. Today Vanessa is a remarkable parent to her two children. I attribute this to her father and to Catherine Schneider, the woman Vadim married after me. And as we went along, I learned some things that have made me a better mother and grandmother.

There is another way to break the pattern of parental disconnect, and that is to be taught

how

to parent. Relational skills are not static. They can be taught, especially during the super-receptive time when a woman is expecting; I know this because I have seen it happen. The gift of good parenting is something that the organization I founded in Georgia in 1995—the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention—teaches disadvantaged young mothers. I have seen how being a good mother is a transforming, empowering experience for a young woman—and how it gives her child a protective resiliency.

I’m proof that you teach what you need to learn.

H

aving lived abroad for so many years, I had few close friends in California, and none with children Vanessa’s age. I was lonely. Sometimes I would swim with her in my father’s pool or I’d take her to the beach house that Vadim had rented and we’d play in the sand. When I was away (which would begin to happen more frequently as my activism increased), she and Dot would live at the beach with him. On weekends I would load Vanessa into my backpack and walk with Vadim along the ocean’s edge. He was now seeing someone new, but we wanted to be friends and it wasn’t difficult. I was happy to spend time with Vadim because he was almost always affable, and having him in my life gave me a sense of continuity.

But it wasn’t only because the marriage was over that I had come home. I was back because I felt compelled to join those who were working to end the war. En route to that joining, however, my attention was drawn to the recent Native American occupation of the island of Alcatraz, a former federal prison in San Francisco Bay no longer used by the government. The goal was to turn the island into an Indian cultural center and bring national media attention to the realities of Indian life: the high rates of unemployment, the low incomes, the high number of deaths from malnutrition and teen suicide; the short life expectancies.

I hadn’t thought about Indians since my childhood days, when I incessantly played cowboys and Indians and asked God to give me an Indian brother. I decided I had some catching up to do and went straight to Alcatraz to find out what was going on. Altogether there must have been a hundred people from many different tribes on the island. Some were older, traditional Indians from reservations; some were student activists from the city. One student, La Nada Means Boyer, a twenty-two-year-old Bannock, became a friend and taught me much about what Native people were facing. She would visit me at Dad’s house, where her two-year-old son, Daynon, played with Vanessa, and I brought her with me on a national talk show. I wanted more Americans to know what I was learning.

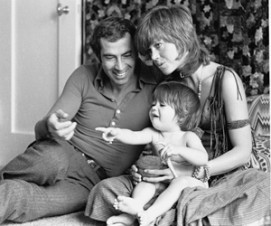

Vadim visiting Vanessa and me in my father’s house. We had separated but were still good friends.

(© 1970 Julian Wasser)

With the help of La Nada and other Indians I met along the way, I learned about the different strategies the federal government was using to rob Indians of the sovereign control that had been guaranteed them over the rich uranium, coal, oil, natural gas, timber, and other resources that lay beneath the ground within their fifty million acres of reservation. It was an important moment for me. Indians had leaped from the cobwebs of old myths and fantasies into a painful present that made me reexamine what my government was doing—much as the book

The Village of Ben Suc

had done two years earlier.

Alcatraz was also a watershed experience for Native people. There young Indians learned from indigenous leaders to value their traditional ways, to understand their lives in a historical context (which, I’ve subsequently discovered, is always a radicalizing experience for people who are oppressed).

It’s not just me. It’s the system.

A then young woman named Wilma Mankiller, for instance, described the Alcatraz experience as a personal turning point, saying that the leaders there “articulated principles and ideas I had pondered but could not express.” Eventually this led her back to her people, the Cherokee, where in 1987 she was elected the first female principal chief in Cherokee history, serving three terms.*

3

One of the qualities that most attracts me to Native people is their attachment to the land. For them the earth is their mother, the sky their father. This has been kept alive in their collective memory through millennia by a tradition of oral history. Wilma Mankiller told me that when a Navajo code talker from World War II was asked how he could help defend a country that had treated his people so badly, he answered, “It’s the land. We are attached to this land.”

Within weeks of my Alcatraz trip, I engaged in my first act of public protest. Several Indians I had met at Alcatraz asked me to come to Fort Lawton in Washington State, which they were planning to occupy. It too was closing, and it was being turned into a park, and inspired by Alcatraz, Indians wanted to make it into a cultural center. I felt I couldn’t say no. I marched with 150 of them and was subsequently arrested, for the first time.

It was not a Vietnam War protest but my trips to Alcatraz and Fort Lawton that morphed me from a noun to a verb. A verb is active and less ego-oriented. Being a verb means being defined by action, not by title.

During these first few months in California, I also decided to act on my long-standing curiosity—piqued by Al Lewis on the set of

They Shoot Horses—

about the Black Panther party. I met some of the leadership, visited their free clinics and hot breakfast programs for children. (Little did I know that one day a girl who had benefited from the Panther program, the daughter of one of the party’s Oakland members, would become a member of my family.) I tried to understand why the Panthers were an armed movement. I thought about how black children in the South had to be escorted to school by armed police. I remembered my father’s childhood lynching story; the time we’d been shot at by white racists because I had been photographed kissing a little black boy. I remembered being told that black militancy had evolved out of the civil rights movement when attempts to end discrimination through nonviolent means seemed futile. I remembered John Kennedy’s words: “Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.” We were reaping what we had sown.

While my natural inclination was to side with the underdog against the bullies, I couldn’t espouse violence as a solution. Meeting state violence with citizen violence felt to me like a dead-end street, literally and figuratively.

My involvement with the Panther party appears in my FBI files as a major focus of the investigation they would soon launch of me, but in truth it was brief and consisted wholly of raising bail money. The party’s FBI files, which I obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, would later show that many undercover agents infiltrated the party. I felt that if I was to be harassed or locked up, I wanted it to be for a group in which I was confident, not for the work of undercover agents. That said, the Panthers, like the American Indian Movement with Native people, helped many African-Americans see themselves within a political context rather than as individual victims. (It’s not me, it’s the system.)

I

soon found myself plunged headfirst into what was about to become the focus of my antiwar activism: the GI movement. I had met GI resisters in Paris, but I was unaware of the extent to which antiwar sentiment was growing among active-duty servicemen. I was planning a cross-country road trip when someone suggested I should visit GI coffeehouses along the way and meet antiwar soldiers. Coffeehouses, I was told, were off-base houses run by civilian activists where servicemen and -women could hang out and learn from visiting speakers about their rights as GIs and about the history of Vietnam.

I soon began meeting people who could give me a crash course in the military. Ken Cloke, a lawyer and history professor at Occidental College who specialized in military law, came to Dad’s house with information about the Uniform Code of Military Justice. So did Master Sergeant Donald Duncan, a much decorated member of the special forces, the first enlisted man in Vietnam to be nominated for the Legion of Merit. Ken and Donald brought me newspaper articles about GI dissent and told stories about the ways servicemen were being denied their constitutional rights.

The U.S. Uniform Code of Military Justice, for instance, was created during the time of George Washington and today seems medieval: Your commanding officer can bring charges against you, appoint your military counsel, select the court-martial “jury,” and even approve or disapprove of the verdict and sentence. A favorite saying in the GI movement back in the seventies was an old quote attributed to Clemenceau: “Military justice is to justice as military music is to music.” Soldiers questioned why, once they put on a uniform, they were deprived of the rights they had been conscripted to defend—the rights to speak freely, petition, assemble, and publish—and that when they claimed those rights, unjust punishments were meted out with no legal recourse.

Attorney Mark Lane and his partner, Carolyn Mugar, were making a documentary about the GI movement, and from them I came to understand the class significance of the movement. While the civilian antiwar movement was primarily white and middle-class, the GI movement was made up of working-class kids, sons and daughters (ten thousand women were in the service at that time) of farmers and hard hats, kids who couldn’t afford college deferments, and a preponderance of rural and urban poor, particularly blacks and Latinos.

I learned that while dissent within the military had started in the mid-sixties mainly as random, individual acts, after the Tet offensive, things began to change. Dissent was no longer a matter of individual acts. GIs began to organize, not just around the growing antiwar sentiment in the military ranks, but in response to the undemocratic nature of the military system itself.

The antiwar GIs represented a minority of our overall Vietnam-era troops. But there was a sizable enough minority of them by 1971 that the army reported an almost 400 percent increase in AWOLs in five years—enough that one military historian, retired Marine Corps colonel Robert D. Heinl Jr., wrote in June in

Armed Forces Journal:

By every conceivable indicator, our army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and non-commissioned officers, drug-ridden, and dispirited where not near-mutinous. . . .

We mustn’t condemn the Vietnam-era soldiers for the things cited by Heinl. Clearly, when you ask soldiers to fight and perhaps die in a war they no longer believe in, you should expect terrible consequences. It would have been hard for the soldiers to believe in a war that by 1970 even moderate American papers and magazines like

The Wall Street Journal

and

The Saturday Evening Post

deemed a folly. When Walter Cronkite began urging a withdrawal, President Johnson said to his press secretary, “If I’ve lost Walter, I’ve lost Middle America.” The GIs and their families

were

Middle America.