My Life So Far (39 page)

There’s something happening here

What it is ain’t exactly clear

There’s a man with a gun over there

Telling me I got to beware

I think it’s time we stop, children, what’s that sound

Everybody look what’s going down

—S

TEPHEN

S

TILLS,

“For What It’s Worth,” 1966

I

N

A

PRIL

1970, I went out to explore America. So much was new. This would mark the start of my needing to experience things firsthand. I can read and study, but to really “get it” I need to sit in people’s homes, see their faces, hear their stories directly, find out what their lives are like. I wanted to put real faces to the troubling facts that I’d been hearing during my three first months back in the States—Native American faces, African-American faces, faces of men in uniform, Middle-American faces. Having lived exclusively on the coasts, what lay between was missing for me—a sandwich with no filling. Living in France had made me feel very American. Now I wanted to know what that meant—not just at the fancy edges but at the center, just as I was seeking my

own

center.

Film director Alan Pakula once said about me, “There seems in her some vast emotional need to find the center of life. Jane is the kind of lady who might have gone across the prairie in a covered wagon one hundred years ago.” Instead I would rent a car and, like a pioneer in reverse, drive east across America.

I set out with Elisabeth Vailland, a friend from France, in a rented station wagon filled to the brim with sleeping bags, cameras, books, my guitar (David Crosby had been giving me lessons), and a cooler for my odd assortment of foods. I was in the anorexic phase of my food addiction, allowing myself only soft-boiled eggs, raw corn on the cob, and spinach. I was anxious that for two months I would not be taking my daily ballet classes—the longest danceless stretch since I was twenty. To compensate, I felt I had to exert rigid control over what I put in my stomach so as not to put on weight.

Almost from the get-go we were swept up in the tumultuous events of 1970—the invasion of Cambodia, the killing of students at Kent State University in Ohio and Jackson State University in Mississippi, and a series of campus uprisings. Certain events from our trip stand out clearly for me, and like snapshots from the road, I will show them to you. But a lot was a blur of drama, danger, and stress. Fortunately both Elisabeth and I kept journals. Less fortunately there are tens of thousands of pages of FBI files on me, which were apparently begun within weeks of my starting the trip (I later obtained these files via the Freedom of Information Act, which was passed post-Watergate).

E

lisabeth was handsome in a Georgia O’Keeffe way. In the press she would be described variously as my hairdresser, my public relations manager, and a Russian dancer. Not unexpectedly, there were hints that we were lovers. We weren’t.

Elisabeth and her by then deceased husband, French novelist Roger Vailland, had shared Vadim’s penchant for whiskey and ménages à trois, and Vadim hoped that my respect for their intelligence would validate his own sexual proclivities. In

Bardot, Deneuve, Fonda,

Vadim wrote about Roger Vailland: “He rejected, with equal rigor, Judeo-Christian puritanism and communist hypocrisy when it came to sex and man’s right to pleasure”

—man’s

being the operative word. The moral premise that Roger Vailland and Roger Vadim shared was that there could be no true love unless it was free from sexual jealousy and emotional possessiveness. Elisabeth not only was in agreement, but often introduced Roger to women she thought would please him. I had once asked Roger if he would be jealous if Elisabeth slept with another man. “That is absolutely forbidden!” he replied.

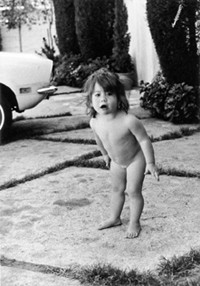

Vanessa, the plucky sprite, in front of Dad’s house just as I was leaving for my first cross-country trip with Elisabeth.

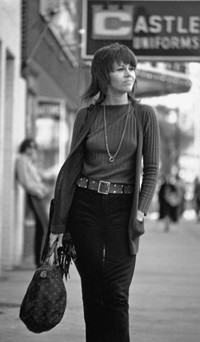

1971. On a quest for meaning.

(Billy Ray/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

“Why?” I asked, stunned.

“Because she would stop loving me.”

“That’s right,” added Elisabeth. “I wouldn’t respect him anymore if he let me come in the arms of another man.”

“That sounds more like hypocrisy than freedom to me,” I said.

“But freedom is not always a mathematical equation,” she answered in that way European intellectuals have, which always made me feel there was something I wasn’t getting. Now I hoped that during our trip I would find out how Elisabeth really felt about her late husband’s libertine ways, and I was prepared to be honest about my own experiences. She was the only person I felt I could discuss the subject with. In fact, I never did get clarity from Elisabeth on this subject, although I decided to broach it as we were driving through Yosemite National Park.

“Did you really not mind that Roger had other women?” I asked her. “Did you really enjoy bringing him other women?” Essentially she stuck to what she’d told me before, claiming that sexually and intellectually it pleased her to please him in that way: “I knew he loved me and I knew that these other women didn’t mean the same to him as I did.”

“I guess I wasn’t confident enough not to feel diminished by Vadim’s philanderings. I never dared to tell him I wanted him to be monogamous, because I was afraid of being thought bourgeois. I thought that maybe if I were a participant, it wouldn’t go on behind my back.”

“Did you enjoy being with women?” she asks.

“I don’t know. I thought I did at the time because I’m so good at becoming whatever my man wants me to be. I can convince myself of practically anything in the name of pleasing. But now that we’re not together anymore, I have been trying to probe what was really going on in my body. In some ways I think I did enjoy it. I liked having an up-close view of the varied ways women express passion. But to go through with it, I’d always have to drink enough to be in an altered state. I always felt scared and competitive—not the best frame of mind to be in when you’re having sex. And I always felt angry afterward, never at the women . . . at Vadim. I usually became chums with the women. It was the only way I could feel human under the circumstances, which made me feel used, not good enough, trampled over for

his

pleasure.

“What about you?” I asked Elisabeth. “Did you enjoy it?”

Elisabeth appeared to answer my question without really answering it. (At the end of that two-month trip, I still didn’t know where she stood on the subject of enjoyment.) I remember wishing I could be more . . . European, more opaque, like her. I suppose that’s why Vadim used to say I lacked mystery.

T

he fact that I participated in threesomes with Vadim was one symptom of my disembodiment, my loss of voice. It’s not as if he forced me to do it. Had I refused, he would have accepted that. I later discovered that his future wives didn’t do it. I have written about it because I know that it is not uncommon for girls to accept another woman into their beds to keep a man.

B

ack to the trip. I loved not having a set itinerary. We would stop whenever we chose and always shared the cheapest motels we could find ($8 a night on average for a shared room), since I had borrowed money from my business manager to pay for the trip. My inheritance was long gone thanks to Vadim’s gambling, and my film salary had been spent on the French farmhouse, which was now for sale.

N

o one recognized me. I didn’t look the way I was supposed to anymore. Three months earlier I still wore the ultrashort miniskirts, revealing blouses, and makeup that had been my costume during my years with Vadim—all designed to attract men’s attention. It hadn’t taken long for me to see that my appearance made it easier for people to objectify me and created a schism with other women. So I decided I wouldn’t dress for men anymore. I would dress so that women weren’t uncomfortable around me. My wardrobe was pared down to a few pairs of jeans, some drip-dry shirts, army boots, and a heavy navy pea jacket. I had stopped wearing makeup. I was often surprised by the

anger

this elicited from people—men, mostly—who I think saw it as a betrayal. Soon articles about “just plain Jane” began appearing, with William Buckley writing, “She must never look into the mirror anymore.” That’s right—I’d looked into the mirror altogether too much during my life.

O

ne day I called a friend in New York, who told me that five thousand women in the city were demonstrating for the legalization of abortion. I wrote in my journal,

Don’t understand the women’s liberation movement. There are more important things to have a movement for, it seems to me. To focus on women’s issues is diversionary when so much wrong is being done in the world. Each woman should take it upon herself to be liberated and show a man what that means.

Did I write that?

Whew! I have included it here because I think it’s important to see how far a person can evolve. I’ve made it abundantly clear that

I

had not taken it upon myself to “be liberated” and show Vadim “what that meant.” I didn’t know yet that when part of the population is viewed as “less than”—culturally, economically, historically, politically, psychologically—it cannot be changed individual by individual. It takes the accumulated efforts of many, working in concert, for systemic change.

Long

after

I started identifying myself as a feminist, I still would not be brave enough to look within myself and identify the subtle ways in which I had internalized sexism—my willingness to forgo emotional intimacy with a man and betray my own body and soul

if

being honest and speaking my voice meant losing him. Put another way, I was the only person I could treat badly and consider that morally defensible.

W

e visited the Paiute Indian reservation, about forty-five minutes outside Reno, Nevada, to join a small protest against the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. With permission of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), the Bureau of Reclamation was diverting water from the Truckee River and Pyramid Lake, on the reservation, to irrigate farmlands owned by white farmers. On the western rim of the lake were about twenty Indians. Some had brought little vials of water to symbolically pour into the lake.

My appearance at this mild protest was the first item to appear in my FBI files. Their informant reported it this way:

The group with Fonda totaled about 200 people of which 40 were in Fonda’s personal entourage. Her group of 40 dumped 20 Gallon jugs of water, brought from California, into Pyramid Lake. It was very peaceful, and no incidents occurred.

. . . Lest we confuse intelligence with “intelligence.”

W

hile we sat waiting to order in the only restaurant on the reservation, several Indian men came in and invited us to sit at their table. One of them, a beefy guy with dark glasses, kept saying we should get some bombs and blow up the dam the white farmers had built—it was damaging the lake. My antenna went up immediately:

an agent provocateur.

The Panthers had warned me about this. We left immediately.