My Life So Far (68 page)

I often think of alternative how-it-could-have-gone scenarios about events in my past that didn’t go right. In the case of my marriage to Tom, I should have taken his face in my hands, looked into his eyes, and said, “I want us to work this out. If you do, too, then let’s each admit our addiction and try to heal, and get help with ‘us.’ I think the issues go deep and I am frightened to do it alone. I am very angry and I don’t know why. We need a referee. Let’s look for a caring professional who can help us work this through.” Instead I would say, “I think we should see a therapist,” and he would say, “No,” and I’d fall silent. Like the magician’s assistant, with body cut in two, I took up permanent residence in my head and ventured out only when in the company of women friends or while exercising, dancing, or getting massaged.

But there are many truths in any relationship. Tom and I shared many interests, and we continued for eight more years after the affair to have an exciting life. When we were working together on a project or a tour and were hitting on all fours, I could forget what was missing. He brought structure to my life, depth of field to my vision, and a sense of how change can happen. Above all, there’s our wondrous son.

I loved Tom’s passion for baseball, how he coached Troy’s Little League team and never missed a game, not once. I always learned so much from him. It was Tom who brought fascinating thinkers like Desmond Tutu, Alvin Toffler, and Howard Zinn into our home; Tom who initiated incredible family vacations that took us to faraway lands like Israel and South Africa, where we would spend time with the keenest minds in a given country. He opened up whole new vistas of ideas for me, and I am very grateful.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

SYNCHRONICITY

Do not leave the theatre satisfied

Do not be reconciled. . . .

You cannot live on our wax fruit

Leave the theatre hungry

For change

—F

ROM

E

DWARD

B

OND,

On Leaving the Theatre

I

N MANY WAYS,

I was starting to come into my own as I found ways to move the social issues that Tom and I were organizing around into mainstream Hollywood films. I found this synchronicity exciting, almost miraculous.

No sooner had I wrapped

Comes a Horseman

with Jason Robards and James Caan than I began filming

The China Syndrome.

It was exciting to once again be working on a project that I felt passionately about with people who shared the passion.

The China Syndrome

dovetailed perfectly with what the Campaign for Economic Democracy was all about: blowing the whistle on large corporations that were willing to risk the public’s welfare to protect their profits.

As Jim Bridges had developed it,

The China Syndrome

told of a Los Angeles TV reporter who is filming with her crew at a nuclear power plant near Los Angeles when something causes panic in the control room. Unbeknownst to her, her cameraman (played by Michael Douglas) films what is going on, but the TV station refuses to air the footage. The cameraman steals the film and shows it to a physicist, who says, “You’re lucky to be alive—and so is the rest of Southern California.” The expert explains that what we have captured on film was a near core meltdown: when a reactor loses its cooling water and the heat of the radioactive fuel becomes intense enough to melt the reactor core—and the steel and concrete of the containment building beneath it, sinking through the earth all the way to China (hence the term

China syndrome

). When the fuel meltdown hits groundwater, clouds of radioactive steam are sent into the atmosphere, potentially killing many thousands of people and contaminating many square miles of land. The plant’s supervisor (Jack Lemmon) refuses to be mollified by the power company’s assurances that nothing important went wrong. He begins his own investigation and discovers structural hazards at the core of the plant’s reactor. He is in the process of seizing control of the reactor when a SWAT team enters the control room and guns him down.

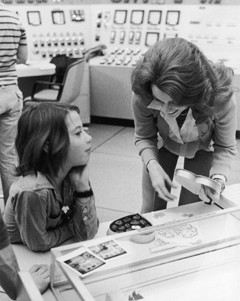

With Jack Lemmon in

The China Syndrome.

Vanessa visiting me on the set of

The China Syndrome.

The China Syndrome

had been playing in theaters for about two weeks, with great box office success. Conservative columnist George Will had called us irresponsible for making a thriller that would scare people about nuclear power because, he said, it was based on fantasy, not fact. Then, on March 30, 1979, while I was in St. George, Utah, filming

The Electric Horseman,

the Nuclear Regulatory Commission announced that high levels of radiation were leaking from inside the reactor of the Three Mile Island atomic power plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Radioactive steam clouds were escaping. The commission admitted there was “the ultimate risk of a meltdown,” and Pennsylvania’s governor, Dick Thornburgh, asked that children and pregnant women within a five-mile radius of the Three Mile Island facility evacuate the area.

It was beyond belief, the most shocking synchronicity between real-life catastrophe and movie fiction ever to have occurred. The film had been doing brisk business, but once Three Mile Island happened it became a blockbuster—not just in the United States but all over the world. People went to see it to understand what had happened in Pennsylvania.

I

mmediately after finishing

The Electric Horseman,

Tom and I went on our third national tour, the first since the end of the Vietnam War, this time focusing on economic democracy, the perils of nuclear energy, and the benefits of energy alternatives like solar and wind. We received a lot of media coverage, mostly due to Three Mile Island.

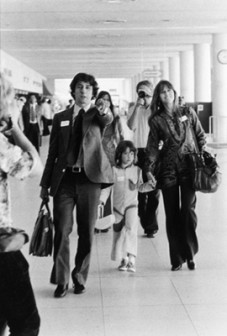

During the IPC tour, walking the gauntlet at the L.A. airport with Vanessa.

(Michael Dobo/www.dobophoto.com)

Along the way it was women who really stood out for me—women like Lois Gibbs at Love Canal, who organized other women to fight against the toxic wastes buried beneath the community and causing serious, even fatal, health problems. There were others like her, housewives who had looked over their shoulders to see who would come to the rescue, only to find it would have to be themselves—and discovering

they

were true leaders.

Karen Nussbaum, my friend from the antiwar days, had gotten me interested in office workers. Karen told me about sexual harassment, about women being on the job fifteen years and seeing men they trained get promoted right past them and made their supervisors, and about clerical workers at some of the wealthiest banks who were paid so little they were eligible for food stamps. This was what got me thinking about making a movie on the subject. During the tour we did events in eight cities to promote 9to5, the national clerical workers organization that Karen started, and when I talked about the idea of a film to the thousands of office workers who attended these events, their excitement was palpable.

We did not see it as a comedy at first. What’s funny about working fifteen-hour days and getting paid for forty hours’ work a week?

Back in Los Angeles I went to see Lily Tomlin in Jane Wagner’s one-woman play,

Appearing Nitely

(later titled

The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe

), and fell head over heels for this woman and her unique, spectacular talent. Driving home from the theater that night, I turned on the radio and Dolly Parton was singing “Two Doors Down.” Bingo! Lily, Dolly, and Jane!

Bruce and I knew that to get Lily and Dolly to agree to be in the film meant my taking the least interesting role, whichever one that turned out to be. Paula Weinstein, my friend and former agent, was now a production executive at Twentieth Century–Fox, and she steered us to writer/director Colin Higgins.

Bruce and I brought Colin to Ohio, to the offices of Cleveland Women Working,*

13

which was being run by my former housemate Carol Kurtz. She had assembled a diverse group of about forty women who took turns telling their office stories while Colin took notes. Just as veterans in the VA had told us of experiences that ended up in

Coming Home,

so it was with the secretaries. When every woman in the circle had had her say, Colin asked a question that took me by surprise: “Have any of you ever fantasized about what you’d like to do to your boss?” The women looked at one another and burst out laughing.

Fantasize? You want to know what we fantasize?

Shazaaam! We had the central idea for our movie—secretaries’ fantasies about doing away with their bosses.