My Life So Far (63 page)

Jim and I talked by phone about the developing character of Kimberly. One day I announced to him that I wanted Kimberly to have flaming red hair. It was a way to tip my hat to a childhood heroine of mine, Brenda Starr, the gorgeous redheaded newspaper reporter in the comic strip of the same name. Jim had liked what I did with the Bree Daniel character in

Klute

when she was alone in her apartment and asked me how I thought Kimberly would be when she came home from work. Did she have a pet? How was her place decorated? I told him that she hadn’t even gotten around to unpacking from her move six months earlier from the San Francisco TV station to Los Angeles. Everything was still in boxes. In

Klute

I had decided Bree had a cat, and in one scene I licked the fork after I’d scraped some tuna fish into her bowl. Kimberly, I said, should have a giant turtle as a pet, something she’d had as a girl, and she talks to it every night when she carries it indoors with her to get it some lettuce (which Kimberly eats before handing it over to her turtle). In Bree’s apartment there was a signed photo of President Kennedy that seemed out of context and made audiences wonder about its significance to Bree. In the same way I wanted Kimberly to have a reproduction of the famous Andy Warhol silkscreen painting of Marilyn Monroe. Like a lot of women, I felt Kimberly would have a special thing for Marilyn because of the tensions she symbolized between humanity and ambition, strength and malleability. No small number of people over the years have asked me about both the turtle and that image of Marilyn. It doesn’t matter that they don’t know

why

Kimberly has these things; it gives her specificity and interest as a person. Jim and I loved throwing in these sorts of odd, conspiratorial tidbits. There was nothing but creative chemistry between us as we worked long-distance to create my role.

The reason it was long-distance was that no sooner did I wrap

Coming Home

than I was off to Colorado to film

Comes a Horseman,

a story about a small Montana rancher just after World War II fighting to save her land from land barons and oil companies. James Caan was the co-star and Jason Robards played the land baron. But the big draws for me on this film were that Alan Pakula, who had directed me in

Klute,

was the director (with Gordon Willis once again the director of photography). It was also a great summer location where Tom, Troy, Vanessa, and I could be together; and I would be reunited with horses in a role that resembled a grown-up version of my childhood friend Sue Sally: a weathered, tough woman who ran her cattle ranch all by herself. It had been more than thirty years since I had been in a saddle, except for filming

Cat Ballou

in 1964, the only other western I’d ever done and it was of an entirely different nature.

Frankly, I was unsure whether I could really play the part of this crusty woman, but Alan again gave me the courage to try. I knew that to do it properly I would have to become like the wranglers who rustle cattle and work the horses on western films. It wasn’t the riding that would be the challenge; like sex and bicycles, that comes right back. But I needed to learn to throw a lasso, rope a calf, round up cattle, and brand and castrate male calves. Not that I had to do all of that in the film, but I needed the wranglers to know that, like my character Ella, I

could

do it all if asked, that I wasn’t a city slicker. The wranglers’ belief in me would give

me

belief in myself—as Ella.

I

was working steadily, without a break, and my career was going full speed. I think about this when I hear admonitions from the powers that be warning outspoken actors to remember “what happened to Jane Fonda back in the seventies.” This has me scratching my head:

And that would be?

The suggestion is that because of my actions against the war my career had been destroyed and that this will happen to them if they don’t get with the program. But the truth is that my career, far from being destroyed after the war, flourished with a vigor it had not previously enjoyed.

I

t was during this period that Tom and I did one of the best things we did together: We bought two hundred acres north of Santa Barbara (two hours from our home) and created a performing arts summer camp for kids called Laurel Springs. Though I didn’t recognize it at the time, what I learned at Laurel Springs laid the foundation for my third-act activism.

I learned to rope for my role in

Comes a Horseman—

here with James Caan.

(© Steve Schapiro)

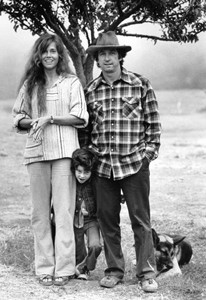

At Laurel Springs Ranch with Tom, Troy, and our German shepard, Geronimo.

(© Steve Schapiro)

The first group of campers at Laurel Springs. Vanessa is in the second row, directly behind the boy holding the camp sign, staring straight into the camera. Troy is way down in the front on the right. Tom is in the hat, back row, right.

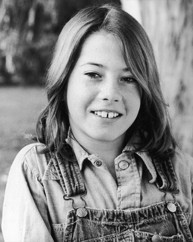

Vanessa, age eleven.

We wanted it to be a place where our friends could send their children—but we had an unusually diverse group of friends, ranging from people in the United Farm Workers union to city council and school board members to former Black Panthers to directors of community-based organizations to movie stars and heads of major studios. These were the varied backgrounds of the children who came to camp, and this diversity was what made it a unique and transformative summer experience that ran for fourteen years, from 1977 until 1991. Girls who had always had maids making their beds shared a cabin with girls who had never had a room of their own. Macho Latino gang member wannabes shared a bunkroom with a pale blond boy who suffered from muscular dystrophy and had to be carried everywhere. His courage in the face of his disability helped the other boys redefine the meaning of being a “real man.”

I learned that even in a short period of time, a camp experience can transform a bully into a brother, a shy girl into someone unafraid to express herself, an urban kid who had been afraid of long grass into a real outdoorsman. I was surprised to see how exposure to nature could be terrifying for an urban youngster who had never seen a night sky filled with stars or felt mud oozing between his toes. Camp gave kids an opportunity to try on new identities. At home and in school, children often get tagged as being the “troublemaker,” the “fast girl,” the “macho boy,” the “nerd.” Camp allowed them to become a tabula rasa, a clean slate, where they could start over and discover other parts of themselves. It always surprised me when parents would tell me, as they dropped off their children for the new camp season, how the effects of last year’s two weeks had remained with their child all year long. As Michael Carrera of the Children’s Aid Society has written, “Young people may forget what you say or what you do, but they will never forget how you made them feel.”

This is the age when youngsters are going through intense changes and too often have no one to go to for help in working through the complicated maze of adolescence. The counselors at Laurel Springs heard a lot of “I have these feelings when I’m around her, like in my body, something happens. What is that?” This gave the counselors the opportunity to explain puberty, what menstruation signifies, or how the boy’s body was changing and new feelings were coming up; that this was totally normal and beautiful; but that having the feelings doesn’t mean he or she has to act on them. (The kinds of things my parents never discussed with me, nor I with my children—to my deep regret.) Campers came to our counselors to talk about their parents’ addictions, about divorce, about death. I learned how important it is for children who’ve lacked physical affection to be held, to feel a warm, loving human touch

without

sexual overtones. Girls who have never had the loving arms of a father in which to safely rehearse tenderness will tend to go straight to sexuality in an attempt to get the craved contact. I learned how transformative it is for children to set goals and achieve them, be witnessed and acknowledged for it. I learned the extent to which deprivation can exist among children of the rich and the emotional richness that can exist among the very poor. I learned the importance of exposing children who have everything to children who have very little, and vice versa. I learned, to my amazement, that approximately one-fourth of the girls at camp had been sexually abused.

Vanessa went to camp from age eight until fourteen and feels it was an important influence. She liked being physically challenged (with the older campers she climbed Mount Whitney) and spending time in the wilderness.

Troy says, “Camp was sort of my great social learning experience. I came to know children of farmworkers, children from all walks of life, through emotional, caring relationships. Regardless of what material possessions you had in the ‘real’ world, at camp people interacted with each other based on your character, not your possessions.”

Troy grew up with the camp, starting out as its mascot when he was too young to attend officially and becoming an assistant counselor by the end. I watched him come into his own over the summers, developing crushes, learning the pleasures of slow dancing. One day when he was about fifteen, I came face-to-face with the realization that he possessed an unusual acting ability. I was watching him rehearse a play in which he played a gay tango dancer. His choices were so brave and free, so much more comedic and physical than mine (or his grandfather’s, for that matter) had ever been. Right then and there I decided to do the opposite of what my father had done with my brother and me. I went up to Troy after the rehearsal and said, “Son, you have real talent. If you decide one day that this is a profession you want to go into, I will totally support you in that decision.” Some years later, that is exactly what happened.