My Life So Far (77 page)

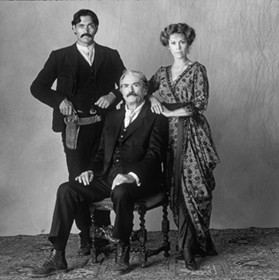

Jimmy Smits, Gregory Peck, and me in

Old Gringo.

(Mary Ellen Mark)

With director Sidney Lumet on the set of

The Morning After.

With Robert De Niro in

Stanley and Iris.

(© Steve Schapiro)

He asked, “Do you love me?” and when I answered, “Yes,” he asked me to write him a letter telling why. Once I’d finished the part about his being a wonderful father, I got stuck. Why couldn’t I think of reasons for loving him? Why did my hand want to write only the anger?

My wonderful, loyal, always intelligent body kept desperately sending me signals by repeatedly attracting mishaps the way abandoned bodies do:

Pay attention to me, listen to me.

This hadn’t happened to me since my injury-prone days in Greenwich when my mother and father’s marriage was delaminating. When I ignored my body’s signals I was paid back in broken bones: fingers, ribs, feet. On his desk Tom kept a photo of me that he’d taken when I broke my collarbone. When I broke my nose in a biking spill during the filming of

Stanley and Iris

he wanted a photo of that as well. Maybe he liked me better broken.

I

was

broken—sexless and fallow. I think it is when people have lost touch with their spirit, their life force, that they become most vulnerable to consumer culture and the toxic drive for perfection. Instead of dealing with my crisis in a real way, I got breast implants. I am ashamed of this, but I understand why I did it at the time. I somehow believed that if I

looked

more womanly, I would

become

more womanly. So much of my life had become a façade; what did it matter if I added my body to the list of falsehoods?

It was for

me

that I did it. In fairness, Tom was adamantly opposed. Here was the woman who had once impressed him by crying in empathy for the Vietnamese women who had mutilated their bodies to conform to a

Playboy

image of femininity and now she was doing the same thing to herself. I knew when I did it that I was betraying myself, but my self had shrunk to the size of a thimble.

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

THE GIFT OF PAIN

No phoenix can arise from no ashes.

—M

ARION

W

OODMAN,

Leaving My Father’s House

O

N THE NIGHT

I turned fifty-one Tom announced to me that he was in love with another woman.

The bottom dropped out of life with a devastation so abrupt and severe that my very existence appeared as a foreign landscape. I felt as though I had just learned I was adopted. Oddly enough I hadn’t seen it coming.

It happened during Christmas 1988. We were all in Aspen, Colorado: Troy, Vanessa, Lulu, Nathalie, Tom, and me, sharing a small rented condo. I didn’t want to spoil everyone’s vacation, so I said nothing—stiff upper lip and all that. So as not to let on there was trouble, I’d wait till everyone had gone to bed and then I’d lie on the living room couch alternately sobbing and reading a novel by Amos Oz.

Never in my life could I have imagined surviving such emotional pain or known that it would assume an

actual physical presence.

I felt blood oozing through the pores of my skin; the pain of a dagger being turned in my heart that now weighed a hundred pounds—allowing me for the first time to understand the meaning of “heavy heart.” I was unable to speak above a whisper for almost a month, or to move swiftly or to swallow food. My throat closed in on itself. Back in Los Angeles, my friend Paula offered me a massage but I fled from the table, unable to stand being touched, unworthy of pleasure. I had been nothing’d.

Given what I have written about the deterioration of our marriage and our lack of communication, you may be wondering why Tom’s blurted admission affected me so deeply. It opened some old, primal rupture, exposing me to an onslaught of pain and grief that went way beyond the end of a troubled marriage.

I don’t think Tom expected it to be the end. I think he believed, as did others, that I had known all along of his infidelities and didn’t really mind. Maybe some part of me

did

know. Maybe that’s why anger would well up when we made love.

I felt overwhelming shame. I didn’t tell anyone for several weeks, not even Paula. When I finally did tell her, she took me in. For more than a week I lived with her and her husband, Mark Rosenberg, in their house on Wadsworth Avenue, right down from where Tom and I had spent over ten years. I didn’t have the strength to ask Tom to move out.

When I finally did decide to call it quits months later, I went back to my house, gathered all of Tom’s belongings into large plastic bags, and threw them out the window into the garden. That helped . . . a little.

But not much. This was so new for me. I had always been the strong one, the Lone Ranger, never blindsided by a pain so profound that my customary arsenal of self-protection was rendered inoperable. The terrain was so unfamiliar that I was unhinged from all my moorings. I would set out for the market and have to pull off the road because my body would be so racked with sobs that I couldn’t drive. I would step outside and wonder why the sun was shining, astonished by this undeniable proof of nature’s indifference. The robin’s-egg-blue sky, unchanged from yesterday, gave an acute sense of permanence to the idea of going forward alone. Death loomed so vividly that I remember insisting it be stipulated in my divorce settlement that Tom not be allowed to speak at my funeral. (I was convinced that he would opportunistically try to do so and couldn’t imagine that we would ever again be close enough friends to justify it.)

It wasn’t

him

I missed as much as an amorphous

us,

the “usness” that celebrated every Easter at the ranch with two hundred of our friends, me dressed up as the Easter bunny, the egg hunts, hay rides, hymn singing, and square dancing; the “usness” that went to Dodgers games with Troy and his buddies from Little League; the “usness” that had, I felt, helped end the war. Usness was gone. And I was fifty-one years old.

Later I realized that both Troy and Vanessa had known the marriage was troubled; but if Tom and I were unable to talk to each other about what was happening, we certainly weren’t able to talk to the children, and they didn’t feel able to initiate the discussion. Vanessa would try to open a dialogue through her anger, but when she did I would shut down. Troy was fifteen and Vanessa twenty when we told them we were separating.

Vanessa was in Africa, working together with Nathalie on a television movie that Vadim was directing. She was acting as language coach, still photographer, and assistant director. I wasn’t sure what to do. I was unaccustomed to reaching out and asking for help. I didn’t want to burden her or disrupt her work, and I also felt so ashamed. Here I’d gone and failed again. But as soon as I told Paula what had happened, she said, “You have to call Vanessa right away. She absolutely needs to know.” Her saying this allowed me to acknowledge how desperately I needed Vanessa with me. Within days she was home, and this meant more to me than she will ever know.

Vanessa had never particularly liked Tom—or rather she didn’t like what she saw me becoming with Tom: giving up myself to suit him (they have subsequently become good friends). Confronted with my sadness, however, I remember her saying (mostly to herself), “Be careful what you wish for.” It was her way of expressing both her own long held hopes that I would leave him and her empathy for me.

She also said, “Maybe now you can spend more time with your women friends who Tom chased away.”

“He did?” I asked, wanting now to know truths that I’d not been able to receive before.

“Mom,” Vanessa said, rolling her eyes heavenward in disdain at my inability to see what everyone knew. “Lois, Julie, Paula—why do you think they haven’t come around much? Tom doesn’t like them and they know it. He was always putting you down, too, but

you

didn’t know it.”

Tom moved to Santa Monica into a rented apartment with a room for Troy, and that’s where Troy mostly stayed. This struck terror in my heart: Was he choosing Tom over me? Was I going to lose my son? But today he explains his decision: “I could see that Dad needed me more than you did. He was in bad shape.” He was right.

I remember asking a friend what I should say to Troy about the breakup and being told, “Say what you feel.”

Say what I feel!

If nothing else, I knew I couldn’t do that. Think of every angry, damning, never-to-be-forgotten word you could call somebody you wanted to murder, and that will give you some idea of what I

felt.

I couldn’t foist that onto my son. A small voice inside was telling me that when the roller-coaster ride was over, my anger would subside and I’d see it was for the best and be grateful that Tom had been the catalyst to end it (which

is

what happened, but it took two years). I spent a lot of time thinking how awful it is for children to become the battleground between warring ex-spouses and how much self-control and maturity it takes to keep a lid on things. Yet I didn’t want to do what my parents had done and what I’d done with Nathalie when I left her father—not show emotion, not encourage a discussion of what was happening that would create a space for them to express their feelings. The trick was to try to do it without anger. Sadness, yes, but not anger.

So I allowed Troy and Vanessa to see me cry, but at the same time I made sure to let them know that a split was a two-way street and that I was partly to blame, which I knew to be true. I talked to them about the primary lesson I was learning from it all: the need to communicate, to recognize feelings, and to express them. Tom and I really didn’t let each other know what we were feeling. Maybe he didn’t try hard enough, or maybe I didn’t try hard enough or didn’t want to hear, or maybe the marriage was meant to be resonant only for a certain period of time (it was—for seven years) and unintentionally we were both looking for ways out.