Napoleon III and the French Second Empire (2 page)

Promulgation of general security law

14 June

End of state of emergency

1859

3 May

France declares war on Austria

11 June

Law regulating cooperation between state and railway compa-

nies

6 July

Franco-Austrian armistice leading to Treaty of Villa-franca

ends militarily successful campaign in Italy

xvi

1860

11 January

Publication of acrimonious correspondence between Emperor

and Pope

22 January

Signature of Cobden–Chevalier commercial treaty with Brit-

ain

24 March

Treaty transferring sovereignty over Nice and Savoy to France

24 November

Publication of decree on political reform

1861

14 March

Emile Ollivier announces his willingness to rally to a liberal

Empire

15 November The Emperor promises financial reforms

1862

29 March

Franco-Prussian commercial treaty

16 April

Declaration of war on Juarez’s government in Mexico

1863

23 May

Law authorising limited liability companies

31 May

General election

23 June

Designation of Minister of State as official government parlia-

mentary spokesman

1864

11 January Thiers in

Corps législatif

calls for ‘the four necessary liberties’

25 May

Law establishing the right of workers to strike

1865

1 January

Government forbids the reading of parts of the Papal encyclical

Quanta Cura

and accompanying Syllabus of Errors from pul-

pits

xvii

1866

22 January Announcement of decision to withdraw from Mexico

3 July Decisive Prussian victory over Austria at Sadowa

12 December Publication of controversial proposals for army reforms

1867

10–13 January Talks between Napoléon and Ollivier

19 January Publication of plans for further liberal reform

March Presentation of proposed laws on the press and public meet-

ings; promulgated 11 May and 6 June 1868, respectively

1868

March French section of the Workers International prosecuted

31 March Official tolerance of trade unions

May Jules Ferry publishes

Les comptes fantastiques d‘Haussmann

1869

3 May General elections begin

8–10 June Serious disorders in Paris

16 June Strike at Ricamarie, troops open fire

6 July 116 deputies support demands for a government responsible

to parliament

12 July Napoléon announces plans for further political reform

13 July

Corps législatif

prorogued; resignation of Rouher

15 August Unconditional amnesty for political offenders

27 December Napoléon asks Ollivier to form a ministry

1870

2 January Ollivier forms a government

5 January Dismissal of Haussmann

26 February Abandonment of official candidacy

21 March Napoléon proposes to establish a liberal Empire

8 May Plebiscite on proposals for constitutional reform

3 July First news of Hohenzollern candidacy

xviii

19 July

France declares war on Prussia

26 July

Decision to withdraw protective French garrison from Rome;

Italian troops enter the city on 2 September

10 August

Following initial military defeats, Cousin-Montauban (Comte

Palikao) forms a conservative government

1–2 September Defeat at Sedan and surrender of army led by the Emperor and MacMahon

4 September

Crowds enter the Palais Bourbon and republican deputies pro-

claim the Republic

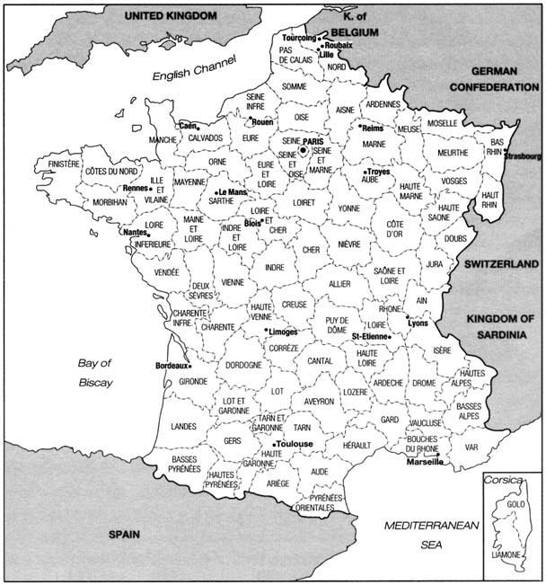

Map

France in 1851

Source

:

France 1848–1851

, Open University Press, 1976

xix

1

Introduction

On 10 December 1848 the nephew of the great Emperor Napoléon was elected

President of the French Republic, gaining a massive majority under the system of universal manhood suffrage introduced following the Revolution of the previous February. The origins of the Second Empire have to be searched for in the ruins of the first. The creation of a dynasty and foundation of a legend were two of the achievements of Napoléon I. Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s major asset was

undoubtedly his name, associating him with a Napoleonic cult kept alive

throughout the intervening years by an outpouring of almanacs, pamphlets and lithographs promoting a legend of prosperity and glory. It had especial appeal in the countryside in which, it ought to be remembered, over 70 per cent of the population still lived. National pride had been incarnated in the historical memory of Napoléon. The July Monarchy (1830–48) had attempted to benefit by association.

In 1833, the statue of the great Emperor had been replaced on top of the Vendôme column in the centre of Paris. In 1836, the Arc de Triomphe, celebrating the glorious achievements of the imperial armies, had finally been completed. The culminating event was undoubtedly the return, in 1840, of the remains of Napoléon I from Saint Helena to their final resting place in the Invalides. Vast crowds had turned out to watch the procession. Louis-Napoléon made every effort to take advantage of this powerful legend, deliberately conceived by the first Napoléon, diffused by the veterans of the Imperial armies, manufactured by printers,

publishers and the producers of all manner of commemorative objects, and given respectability by the government of Louis-Philippe. At Strasbourg in 1836 and then 1

Boulogne in 1840, Louis-Napoléon had attempted to seize power. He had appeared in uniform, behind a tricolour capped by an imperial eagle and sought to raise the local garrisons. Although pathetic failures in themselves, these adventures had at least helped to establish him in the public mind as the Bonapartist pretender. For much of the population, the Imperial years stood in marked contrast to the

impoverishment and political strife which seemed to have accompanied its

successor regimes. The misery of interminable war during the First Empire

appeared largely to have been forgotten. Louis-Napoléon’s electoral victory was evidence of the importance of historical myth but in the particular circumstances created by the long mid-century crisis, a complex series of inter-related economic and political crises with devastating social consequences. It was this situation which made it possible for Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, previously known for his two adventurous but essentially mad-cap attempts to seize power through military coups, to finally succeed.

Varying approaches to the period

Historians have usually presented the Second Empire as a political drama in two acts. Their focus has primarily been on high politics and the character of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte. The regime’s ignoble origins in a

coup d’état

and the tragedy of its final humiliating collapse in the war of 1870 have loomed large. As ever, the approach taken by historians has been shaped by the concerns of their own time. At first, the dominant trend – as republicans struggled to secure the Third Republic (1870–1940) – was marked by bitter hostility. The combination of a carefully researched political narrative with moral indignation was exemplified by the journalist Eugène Ténot in two works on the

coup d’état

, published even before the Empire had disappeared. At its height in the 1930s and 1940s it identified Napoléon III as a precursor of Fascism. More positive assessments were also beginning to appear. Thus, from the inter-war years of the twentieth century and during the period of reconstruction following the devastation of World War II, historians’

interests shifted to reflect a widespread concern about French ‘backwardness’ and

‘stagnation’. They looked for lessons from what were judged to be the regime’s constructive ‘technocratic’ achievements and, particularly, the reconstruction of Paris, the creation of a ‘modern’ transportation infrastructure and, more broadly, the establishment of the conditions for rapid economic growth. More recently, our knowledge of the period has been enlarged considerably by social historians 2

working at community or regional level. The traditional ‘top down’ approach to history with its focus on ‘high’ politics has been neatly supplemented by a ‘bottom up’ perspective much more concerned with the experience of the urban and rural masses.

State and society

The study of political leadership is undoubtedly of crucial importance; so too are questions about the nature of social and political systems. Their structures, both formal and informal, regulate the ways in which political authority can be exercised and provide environments for the creation of more diffuse political cultures. If the objectives political leaders set for themselves need to be identified, so too does the context within which they operate. The factors serving to reinforce or to restrict their authority are of obvious importance. It should be borne in mind also that governments are far from being unitary enterprises, but are frequently riven by internal rivalries and marked by a practical incapacity to achieve their objectives fully. Effectiveness depends in part on institutional design, but additionally on economic and social circumstances and frequently on the impact of largely

uncontrollable external events. Thus, France during the Second Empire might be seen as a society in transition, undergoing (as so many parts of the contemporary developing world) an accelerating process of industrialisation and urbanisation, as part of which farming was increasingly commercialised and the rural world

integrated into the national society. This might be described, without too much exaggeration, as the result of a communications’ revolution, the product of the ongoing improvement of transport, of rising literacy levels and the development of the mass media. As a result, politics was not concerned simply with state–society relationships, but with the efforts of members of old and new elites to reach a compromise over the share of political power, as the vital means of securing their control over a rapidly changing, if still predominantly rural, world.

This pamphlet will attempt to build on the work of other historians and, most notably, that of Alain Corbin, Louis Girard, Vincent Wright and Theodore Zeldin (see Bibliography). While concentrating on a particular period and regime, the essential approach will remain problem orientated, although in the limited space available many crucially important questions will simply be noted rather than resolved. It will focus on the machinery of state, on the personnel involved (see also Price 1990: 27f), on policy formulation and upon its impact. Its initial emphasis, in 3

this introductory chapter, will be on state–society relations viewed from the perspective of the state. Its subject matter will include some of the central issues of socio-political history, including the identity of those individuals and social groups enjoying privileged access to the state apparatus. Obviously, ‘the action of the state as an institution depends . . . on the people who direct it’ (Birnbaum). These included the ‘dictator’ himself, Napoléon III, who enjoyed considerable personal power, as well as leading figures in the bureaucracy and military and influential members of the wider social elite from which they were recruited. Relationships between the Emperor and political elites as well as the internal dynamics of these groups will be one of our central concerns. The freedom of action of the head of state would vary considerably over time along with the willingness of these elites to accept his dominant position. Efforts to reinforce his authority and appeal over the heads of elites to the ‘sovereign people’ (employing such devices as the plebiscite together with electoral manipulation) enjoyed only limited success. As a result, some degree of agreement with (as well as substantial cohesion within) this political elite would appear to be a pre-requisite for effective state action. Other relevant questions include: What were the means by which its agents sought to legitimise their authority and how effective were they in penetrating society and in achieving their goals? How were the activities of state agencies perceived by the ruled and how did they respond as individuals and also as members of different social and regional groups? This process of interaction, both with the state and each other, occurred within a society which remained profoundly inegalitarian.

Inevitably, the capacity for political mobilisation varied considerably. Moreover, overt and straightforward class conflict was only episodic and offers only a very imperfect guide to analysis. As a result, a wide range of additional questions suggest themselves. The list that follows is far from inclusive. It needs, however, to include at least the following: What were the effects of government policy and a concurrently accelerating process of industrialisation on a social system