Nelson: Britannia's God of War (19 page)

Read Nelson: Britannia's God of War Online

Authors: Andrew Lambert

As the bombardment had been abandoned it was time to seek out the Mexican treasure convoy. Nelson and Troubridge planned a combined operation with four thousand troops, similar in concept to the operation at Capraja. Their scheme was based on sound intelligence. Scouting and cutting-out operations around the Canary Islands encouraged Jervis to fall in with Nelson’s plan. He was given three seventy-fours, three frigates, a cutter, and a small mortar boat, and their captains were among the best of Jervis’s protégés – Troubridge, Hood, Bowen and Fremantle. Jervis didn’t bother to tell Spencer about the operation until early August, when he stressed there was no idea of keeping Tenerife.

22

Their target was a large merchant ship and her cargo, which Nelson thought might have been landed. Unfortunately the local defences were in good repair, and adequately manned by 800 professional soldiers, 110 French sailors and 700 local militia. The Commandant General of the Islands, Don Antonio Gutierrez, was an experienced officer, unlikely to collapse in face of British bravado.

En route for Tenerife, Nelson called his captains to conference four times; he remained Lord Hood’s man at heart. His final plan, as at Capraja, was to land at a distance from the enemy, secure a commanding position and send in an ultimatum. Over nine hundred seamen and marines were to be put ashore in a carefully planned operation. The night landing on 22 July was hampered by heavy weather, and when the alarm was raised ashore Troubridge, in tactical command, hesitated and went back to consult Nelson just when he should have pushed on. It was a rare failure for so bold and enterprising a man. A second attempt to capture higher ground in broad daylight left the men roasted by the sun, and then dismayed to find they had climbed the wrong hill. They retreated in bad humour.

Now Nelson faced a hard decision: he could admit defeat and sail away, or try again. After a twenty-four-hour delay for bad weather and another Council of War, he elected to launch a frontal assault on a well-defended town at night, basing the decision on the report of a Prussian deserter and the local knowledge of Thomas Thompson, captain of the newly arrived

Leander

.

All the officers knew this would be a desperate affair, and Nelson was not going to let anyone else lead it. Failure was possible, but not until he had tried himself. Knowing the risks were great, he deliberately burnt the letters from his wife.

In attempting an assault on well-prepared shore defences from the sea, at night and with only small arms, the British were relying on surprise to unsettle the defenders. If the Spaniards stood to their guns and defended their positions until daybreak, the attack must fail. Around midnight the boats went in, planning to land on the Mole and storm the central castle. Inevitably strong currents dispersed the boats and the men came ashore in a variety of locations. Once roused, the Spaniards produced a terrific volume of fire that stalled the attack in all areas. The operation had failed.

Nelson himself never reached the shore. As he was preparing to land from the

Seahorse

’

s

barge, a musket ball shattered his right arm just above the elbow. With a major artery cut through, he could have bled

to death, but his stepson Josiah quickly staunched the flow and applied a tourniquet. This act, which Nelson acknowledged had saved his life, was heavily featured in Clarke and McArthur’s official life. It distracted attention from the failed attack, and ensured Fanny could give her son some credit.

Although badly wounded Nelson remained perfectly calm, deliberately placing his uncle’s fighting sword in his left hand. The sword was a talisman that he always carried into battle, until he forgot to buckle it on on the fateful anniversary of Suckling’s triumph. The barge now carried Nelson back to the squadron. A small force that gathered on the Mole were pinned down by heavy fire. When the officers tried to lead them forward they were hit: Richard Bowen was killed, Fremantle and Thompson were wounded. The Spanish officers had placed their cannon well; at such short range, blasts of canister shot were devastatingly effective.

While the landing force had been large enough, it had not arrived together, nor had the whole force actually landed. Some boats sheered off when faced with a rocky shoreline and heavy fire. As a result the attacks were on a small scale and easily broken up. After sunrise on 25 July Hood and Troubridge managed to extricate the force ashore from a desperate situation, but only by admitting defeat and promising not to come back.

Josiah had taken Nelson back to the fleet, although the admiral insisted on stopping to rescue men from the cutter

Fox

,

which sank suddenly. He also refused to board the

Seahorse

for treatment, as Fremantle’s wife was on board and he had no news of her husband. Arriving alongside the

Theseus

,

he refused to be carried aboard, using his left arm to climb up to the companion way. Once there he told the surgeon to prepare his instruments, as he knew the arm must be amputated. ‘He underwent the operation with the same firmness and courage that have always marked his character’, reported midshipman Hoste – although that did not prevent Nelson recalling the terrible sensation of cold steel cutting into living flesh. Within an hour he was back at work, signing, with his left hand, a demand for the Spaniards to capitulate and surrender the Manilla galleon. It was never sent. Instead, the

Theseus

came under fire from the shore batteries, cut her cable and stood out to sea.

Nelson’s state of mind at this point can hardly be imagined. Mutilated and in agony, he was uncertain of the situation ashore, but

well aware that the signs were not good. As the shore party marched away with their arms Gutierrez allowed them to think they had been defeated by eight thousand troops, a neat piece of disinformation that would reinforce Hood’s promise not to return, and quickly became part of the Tenerife legend. Had the garrison been so large it must have been known before the attack, and condemned the operation as insane.

Until the men were safely back afloat Nelson’s professional concern for duty masked his inner feelings, but once he had finished bolstering the morale of his juniors he gave way to the inevitable shock and depression. His first thoughts were to explain the failure to Jervis. Characteristically he made no mention of the Councils of War, or the advice of others, taking full responsibility while praising the heroism of his followers. This was greatness in adversity. It explains why so many men wanted to follow him. Under his guidance, they would be able to use their skill and contribute to the planning, without being held to blame, even in private, if things went wrong.

To his report, he attached an early example of his left hand at work. ‘I am become a burthen to my friends and useless to my Country … When I leave your command I become dead to the world; I go hence and am no more seen.’

23

It was not surprising that he should close with a paraphrase of Psalm 39, which had just been read over the dead at the burial service; it was a familiar refrain from the life of a clergyman’s son, and all the more affecting from the number of his closest friends who had been killed. Jervis’s protégé Bowen was a terrible loss, while one of Nelson’s own favourites, Lieutenant John Weatherhead, shot in the stomach, could not live.

It took nearly three weeks to get back to the fleet off Cadiz, time that hung heavy on his mind. Desperate for moral support he turned to Jervis, who rose to the challenge, opening his reply with the matchless phrase, ‘Mortals cannot command success: you and your companions have certainly deserved it, by the greatest degree of heroism and perseverance that ever was exhibited.’ He added the promise of a ship home, promotion for Josiah and further rumours of imminent peace to lessen the blow of leaving.

24

He took full responsibility for the attack in his public report, and wrote to Fanny to report that Nelson had added considerably to his laurels, while his wound was not dangerous.

25

This was at once great and considerate.

Four days later Nelson shifted across to join Fremantle and the

other invalids on the

Seahorse

.

He was going home for the first time in five long years. This was not how he had envisaged his homecoming – hero of the battle and commander of detached squadrons. He should have come back in glory, with prizes and plunder, not mutilated and surrounded by reminders of his greatest failure.

26

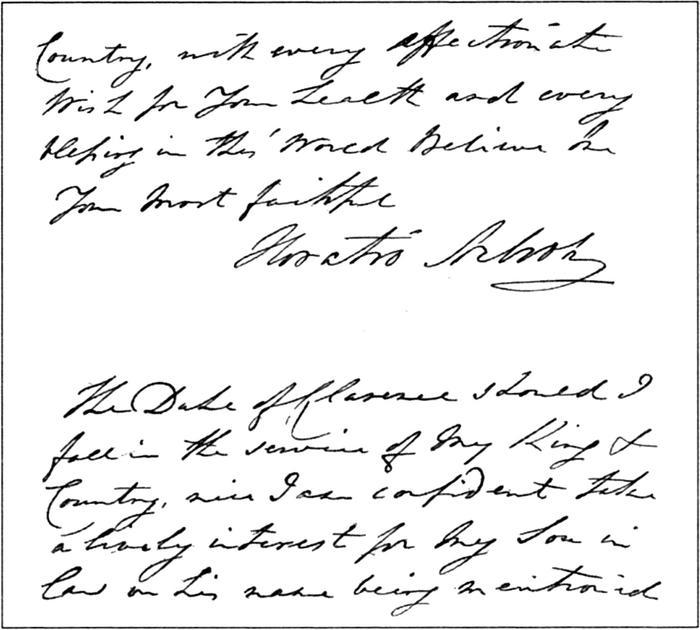

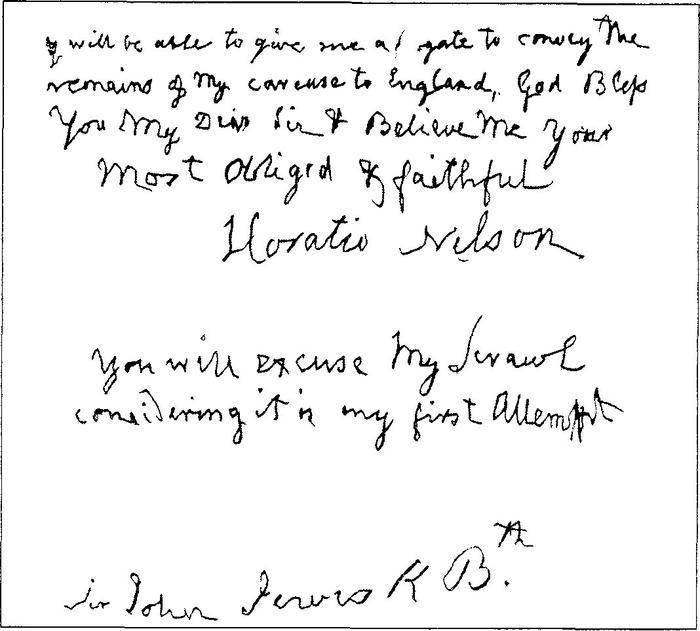

The last letter written by Nelson with his right hand, and (opposite) the first letter written with his left hand

Having dealt with the professional consequences of defeat, Nelson wrote to Fanny, expressing the hope that she would be pleased by a left-handed letter, and a claim he was ‘never better’ – a phrase that hardly did justice to his physical or mental state. He praised Josiah’s actions, and trusted his country would not leave him without pecuniary reward. On reaching the fleet, he added a few lines to report that he was ‘perfectly well’, and that Jervis had promoted Josiah to the rank of Master and Commander. In reality he was deeply depressed, and in great pain.

Nelson would have been comforted had he read Jervis’s correspondence with Spencer. The two Earls were already taking a dangerous

pleasure in discussing their remarkable new admiral. St Vincent was anxious that the First Lord did not think Nelson had been permanently crippled: he had returned from Tenerife ‘in such health that nothing could prevent his coming on board the

Ville

de

Paris

… I have very good ground of hope that he will be restored to the service of his king and country.’

27

Dark as the horizon must have seemed, Tenerife had not harmed Nelson’s career: as long as he made a full recovery from his wound he could return to service. His days at the head of the boarding party were now past, but he would always find brave men to fill that role. It would be as a fleet commander and strategist that he would establish his reputation as Britain’s greatest admiral.

*

Landing at Portsmouth on 1 September, Nelson was immediately back in contact with his admirers. Commander in Chief Sir Peter Parker had made him a captain, while the cheering crowds testified to his fame. Arriving in Bath, he found that this phenomenon was not confined to the dockyard towns: civic greetings competed for his attention with glowing letters from Hood and Clarence. Within a month he was

anxious to return to sea, but still suffering from the slow healing of his amputation. In constant pain, he required opium to sleep. Consequently, when Locker persuaded him to sit for a portrait, to meet popular demand, the face that Lemuel Abbott captured was ravaged by pain. It was also focused and powerful. This was no boyish enthusiast, it was a man of war, a man who had tasted victory and defeat, loss and suffering.

28

Although the amputation had been hurried, it was a silk ligature, tying off an artery, that caused the problem. These were meant to come away as the artery withered, and one of the two in Nelson’s wound did so; the other hung on far longer, possibly attached to a sinew, but the only cure for the pain it caused was time. When the rogue ligature finally came away in early December, Nelson requested that his local church make reference to his thanksgiving. He rewarded the young surgeon who had dressed his wound by making him surgeon of his flagship the following year.

The months spent ashore between Tenerife and the Nile gave him the chance to learn how to operate with his new writing hand, to adjust his clothes and equipment, and to increase the strength and dexterity of his left arm. The mental adjustment was if anything less difficult than the physical. The powerful strain of religious resignation in Nelson’s thought ensured that he saw the loss as God’s will – a chance of battle, and only one of a catalogue of wounds he would continue to suffer.

29

Wounds were tokens of glory and honour, not defects to be hidden. He never tried to hide his empty sleeve, pinning it across his chest, frequently joking about his loss and naming the stump his ‘fin’. The missing arm even featured at his investiture into the Order of the Bath, at St James’s Palace on 27 September. When the King thoughtlessly blurted out that he had lost his arm, Nelson quickly introduced Edward Berry as his ‘right hand’. This ancient ceremony, rich in imagery, pageant and theatre, was a key element in Nelson’s recovery. The act of putting a star on his breast made Sir Horatio Nelson a real hero: his countrymen looked on him as a talisman, while the Freedom of the City of London testified to the commercial impact of his services. He was ready to make the next step.