Nelson: Britannia's God of War (39 page)

Read Nelson: Britannia's God of War Online

Authors: Andrew Lambert

While the smoke of battle hung thick and the situation appended uncertain, Parker watched from afar. At 13.15 he ordered signal No. 39, ‘Discontinue the Action’, to be hoisted, and enforced by firing guns. No one on the

London’

s

quarter-deck that afternoon ever explained this action. Once again Parker’s underlying irresolution burst through, propelled by uncertainty, anxiety and lack of confidence. Personally brave, he was unnerved by the responsibility of battle, not the shot and splinters. The signal applied to every ship, and was obligatory. Parker never said why he flew it. Nelson did not mention it in his official report, but he was once again faced with an order from a superior officer that he considered dangerous, and impossible to execute. Unlike Keith’s foolishness over Minorca, this contained the seeds of immediate tactical catastrophe. Any attempt to get out of the King’s Deep under fire from a position close to the Middle Ground would have left his squadron in chaos, with many aground, giving the Danes every prospect of a remarkable victory. When the signal was pointed out Nelson had it acknowledged, as was proper, but demanded that his own No.16 was kept aloft. He did not repeat Parker’s signal. With Stewart and Foley at his elbow, he played out, legend has it, a little joke: saying, ‘You know Foley, I have only one eye and I have a right to be blind sometimes,’ he lifted his telescope to his right eye and announced, ‘I really do not see the signal.’ The more authentic report given by Minto the following month was: ‘I have only one eye, and it is directed on the enemy.’

61

The exact words matter less than the sentiment: Nelson was going to disobey Parker, and face the consequences. He could see the Danish line crumbling, ships slipping out of the battle, guns falling silent and his own firepower superiority increasing with every minute. There was no reason to fear defeat: although the Danes were holding out a little longer than he had expected, they would be beaten within four hours. Only a heartbroken

Riou, far closer to the flagship, acted on No.39: ‘What will Nelson think of us?’ he lamented. As the

Amazon

showed her stern to the Trekroner, a round shot cut him in two. For Nelson this was ‘an irreparable loss’.

62

Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Graves asked his signal officer to check Nelson’s response, and elected to follow his commander, not Parker. The battleship captains shared his faith in their admiral, and stayed put.

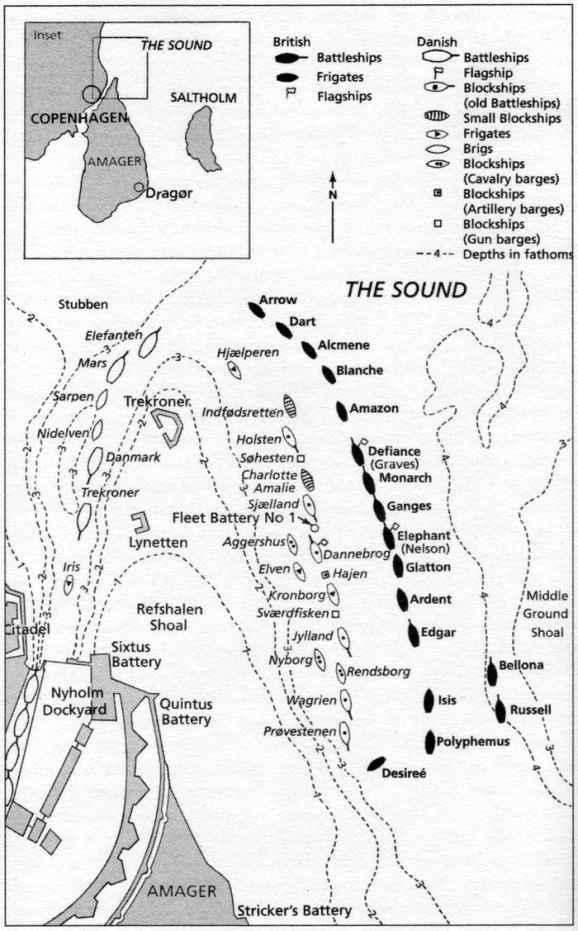

The battle of Copenhagen

Nelson followed up the signal incident with another stroke of genius. He had defeated the less powerfully armed Danish vessels, and if this had been a sea battle the Danes would have surrendered long before, their masts shattered. However, they were at anchor. So at 13.45 he went below and wrote a letter to the Danish Government, ordering Danish speaker Frederick Thesiger to take it by boat under a flag of truce along the disengaged side of the line. Thesiger landed at the Citadel at or before 15.00. The letter spoke of events that had not occurred when Nelson wrote, notably the capture of the Danish blockships, and warned of serious consequences if the Danes did not stop firing. Many have argued that this was a trick, a

ruse

de

guerre

, to escape a difficult situation. His own explanation was simple humanity, and he was not a competent liar. In reality his immaculate timing was the key. He knew how long it would take to get the letter ashore, and reckoned, very nicely in the event, that in an hour it would all be over, and his letter would be read by men facing utter defeat. He had not won when he sent the letter, but he had when it arrived.

It was also a neat political stroke, ending the battle and limiting the damage to Anglo-Danish relations. As he would stress to the Crown Prince, the real problem was Russia, so an emollient note, letting the Danes know they had done quite enough for honour, and warning them of the consequences if they did not see this, was just what the situation required. When the Danish Crown Prince received Nelson’s letter, he could see that the defence line had stopped firing, and that none of the ships had an ensign aloft. Parker’s squadron was working into range, and his leading ships were firing on the Danish forces north of the Trekroner. He took the hint that it was time to negotiate, because he knew the battle was lost. To avert the impending bombardment of the arsenal, dockyard and city he ordered a ceasefire, and sent his English speaking

aide

de

camp

,

Lindholm, out to meet Nelson. On his arrival Nelson also ordered a ceasefire. The Danes wanted to avoid further fighting, but did not dare accept the terms that Parker conveyed

to Lindholm that evening: to leave the Armed Neutrality and join Britain. With guns falling silent the British ships worked out of the King’s Deep, although two went aground, including the

Elephant

. Nelson returned to the

St

George

for the night, exhausted and anxious. He need not have worried: it was obvious to all who had won the battle, and what that said about the principal protagonists:

What another Feather this is to Lord Nelson. I can’t help thinking, what the difference of feelings there must be between him and the Commander in Chief, to let him get such a Victory, and the other to be looking on – for God’s sake say nothing about this.

63

The statistics of the battle told their own story: the British lost 254 dead and 689 wounded, the Danish losses were around double this. The British had taken twelve of the eighteen Danish vessels, but only the

Holsten

was worth refitting and sending home.

64

The rest were too old or unusual to warrant the cost of repairs. Most were stripped of any useful stores, bronze guns and equipment, before being burnt, usually at night.

65

On the morning after the battle, all seven British bomb vessels lay in the King’s Deep, ready for action. These ships were fitted with thirteen-inch mortars, firing two-hundred-pound shells filled with ten pounds of powder up to four thousand yards. This was far beyond the accurate range of any existing cannon, and as bomb vessels were small targets they could bombard a port or city with impunity. They were now in range of the dockyard, arsenal, the Royal Palace and key parts of the city. The Crown Prince considered fighting on, to prove his loyalty to his allies, but the result would have been useless sacrifice. Instead he pressed for a negotiated settlement that would appease the Tsar and the French: to accept the British terms risked the loss of Norway and the mainland provinces; to reject them would cost him Copenhagen and the fleet.

On 3 April Parker sent Nelson ashore to negotiate. Having completed his report and visited the ships that had fought so well the previous day, he landed at the Customs Quay with Hardy and calmly walked down the street to the Palace. The crowd showed no hostility: many wanted to get a glimpse of the hero. Nelson opened the business by flattering the Danes on their courage, and gave the Crown Prince two options: accept Parker’s terms or disarm the fleet. The latter offered the Crown Prince and his Foreign Minister an opening. Anxious to attack Russia, Nelson was prepared to ignore explicit government

orders, and open a political negotiation. He would settle for neutralising Denmark while the fleet set about Russia. He stressed that Denmark would not profit from a Russian-dominated Baltic, and that their neutral trade would not survive. He was anxious to get to Reval before the Russians could retreat to Cronstadt – indeed, he told St Vincent he would have been there two weeks earlier, except that Parker would not pass Denmark without a political settlement, fearing their batteries could stop his supplies. Such feeble conduct made him ill and anxious to go home.

66

His terms were lenient, because Britain held the Danish colonies and trade hostage, and could easily burn Copenhagen. It was best not to do so, because it would make reconciliation more difficult.

67

The purpose of the armistice was to move Hyde Parker.

68

After six days of bluff and counter-bluff, the British settled for Danish neutrality for a period of fourteen weeks, the time Nelson believed he needed to deal with the Russians. The terms were made that much better for the Danes by news that the Tsar had died; they no longer needed to fear reprisals from their mighty ally. The British did not hear this news for another two days. While the negotiations were under way, Nelson placed a large order with the Royal Copenhagen Porcelain works,

69

an event still celebrated in the company’s Copenhagen showroom!

While the negotiations dragged on Parker kept the bomb vessels ready, fitted out the

Holsten

as a hospital ship, and repaired the fleet so he could proceed as soon as he had finished with the Danes. His official dispatch contained effusive praise of Nelson’s zeal. Fortunately for his peace of mind he had no idea that St Vincent had just written a reply to his letter of 23 March, expecting the complete destruction of the Danish fleet.

70

As soon as the armistice had been signed on the morning of 9 April, Parker exploited the terms, demanding water and fresh victuals. He also moved the bomb vessels.

Parker’s report stressed that the armistice kept the fleet effective and the narrows open for the rest of the campaign, while any attack on Copenhagen would have rendered the critical bomb vessels useless for operations against Russia.

71

On 13 April the fleet passed over the Drogden Shallows into the Baltic, the two flagships having to take out their guns to reduce their draught. On the same day Captain ‘

Bounty

’ Bligh, now commanding the shattered

Monarch

,

convoyed

Holsten

and

Isis

back to Britain.

72

These three ships were too badly damaged

for local repairs. A frigate was sent to locate the Swedes, and offer them the same terms as the Danes. When she returned on 15 April, reporting that they were at sea off Carlscrona, Nelson had himself rowed from the

St

George

to the

Elephant

,

in case the fleet went into action while his flagship was disarmed.

*

The political situation in the Baltic, meanwhile, was changing rapidly. News of Paul’s murder and the change of Russian policy reached London on 13 April, in time to influence the initial response to the battle. The Cabinet elected to exploit the new Russian policy, suspending the order of 14 March to attack Reval and the other Russian ports. Now Parker should check if the embargo on British merchant ships had been lifted. He could suspend hostilities as long as the Russians were prepared to negotiate and the Revel Fleet did not attempt to leave harbour. Hostilities could be opened after twelve hours’ notice.

73

Arriving off Carlscrona on 19 April, the Swedish fleet was sighted at a distance, and Parker signalled for a chase, but on further inspection it was clear that they were secure inside the rocky archipelago. As the fleet waited for reinforcements off Bornholm Parker was once more paralysed by indecision. Should he sail for Revel, or watch the Swedes?

Back in Britain there was no doubt who had won the glory. Lord Spencer stressed that Nelson ‘need be in no anxiety about the feelings of the Country on your account. They give, as they ought, the whole merit in so very hazardous and difficult an attack to the man who carried [it] into execution, and the battle of Copenhagen will be as much coupled with the name of Nelson as that of the Nile.’ Furthermore, ‘the universal applause of a grateful nation and having already been looked up to as the best proof of our Glory in War, will most probably be blest as the principal instrument of procuring an honourable peace’.

74

The King and Parliament offered their thanks, while St Vincent sent the news to the Lord Mayor of London, praising Nelson for having ‘greatly outstripped’ himself and promising to attend to his wishes.

75

These wishes were, as ever, headed by the desire that his favourite brother Maurice be promoted. This was done: Maurice would have an extra

£

400 a year, but not a seat at the Navy Board. Davison reported him contented,

76

but Nelson himself was not. Sadly Maurice died suddenly on 24 April.

77

It was a terrible loss for a man who loved his family above all things.