Nelson: Britannia's God of War (36 page)

Read Nelson: Britannia's God of War Online

Authors: Andrew Lambert

PART THREE

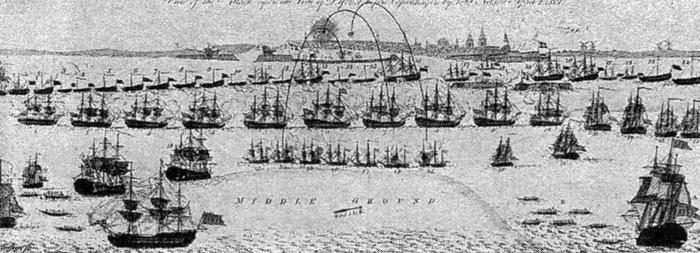

Bombs in air: the attack on Copenhagen

CHAPTER XI

After eight weeks of domestic chaos and mental anguish ashore, Nelson wanted to get back to sea, and both Lord Spencer and St Vincent, now Commander on Chief of the Channel fleet, were anxious to oblige him. Over the next twelve months he would prove himself an inspirational symbol of British resistance, ensuring that he was the inevitable choice for the Mediterranean command when war broke out again.

With the failure of the Second Coalition British strategy changed. As Russia switched from ally to armed neutral it was clear that without a Continental ally, maritime power would be the key resource for Britain.

1

This suited Nelson and his approach to war. His contemporaries were reluctant to engage in coastal offensive operations, and showed little interest in grand strategy. Sir Hyde Parker’s command of the Baltic fleet and Lord Keith’s blundering and fractious direction of the Mediterranean naval offensive in 1800 and 1801 were significant examples of a wider problem. The Royal Navy needed to be reprogrammed for the new circumstances of total war for national survival. Statesmen, soldiers and sailors of the ordinary sort were bogged down by precedent and rules, but Nelson soared above them. Although his status as a national icon was clear, his role as the intellectual force behind national strategy was but dimly perceived in Whitehall. Most

still saw the Nile as a fortunate event, and the later campaigns around Naples as inglorious embarrassments. The Baltic campaign would be a salutary reminder that Nelson was irreplaceable.

The shift in strategy followed the failure of the Continentalist foreign policy that based British security on temporary coalitions with great powers. The inability of Austria and Russia to make any headway against the French on land left that policy in ruins. Now the British had to rely on sea power to counter French military prowess, limiting their successes to Europe, while hamstringing their economy.This new strategy had several requirements: to cripple or destroy the enemy’s naval resources, to secure British assets, trade and interests, and to deny the enemy any opportunity to strike at Britain. The core of this strategy was an economic blockade, imposed by the fleet, based on the legal right asserted by Britain to stop and search any neutral vessel, to establish the ownership and destination of the cargo. This was the principal weapon in the national armoury, and so important that Britain would fight the whole world to uphold it.

The impact of the change in strategy would be particularly apparent to those standing on the sidelines, and exploiting the conflict for economic gain. The destruction of French sea-borne commerce, and the occupation of the Dutch Republic, left a large gap in the provision of shipping between the East and West Indies and the blockaded ports of French-controlled western Europe. This opportunity was being exploited by neutral shippers, notably Denmark, which had expanded its own small Asiatic trade to cover the carriage of Dutch goods from their far larger Eastern empire. This was an abuse of neutrality, but the British had largely ignored the subject until 1800 when the nature of the war began to change.

2

The new strategy required the imposition of truly effective blockades, and the application of the severe code of maritime belligerent rights developed in the mid-eighteenth century to deal with neutral carriers.

In 1798 Denmark had adopted an offensive neutral policy, using warships to convoy merchant ships her ministers knew were carrying Dutch goods past the British blockade. This revival of ideas from the1780 Armed Neutrality was highly dangerous, and required far more adept direction than the Crown Prince could provide. After a few incidents the ‘sovereignty of the seas’ was asserted by the dispatch of British warships to Copenhagen in August 1800, and the two sides compromised, but wider events imposed a different outcome.

The unstable Tsar Paul of Russia, who had joined the Second Coalition full of enthusiasm, was now disenchanted with his allies. The Austrians had been more interested in securing territory in northern Italy than defeating France, while the failure of a Russo-Britishcombined operation in Holland prompted severe recriminations on both sides. The final straw came in September 1800 when the British accepted the surrender of Malta, the most enduring fruit of Nelson’s victory at the Nile. Initially the British had agreed to include their allies in the process, but Dundas’s growing alarm about Paul’s aims, and indeed his sanity, prompted a reconsideration, just as his new strategy of standing alone took shape. This transformed the role of Malta from a bargaining chip, which could be used to keep the Tsar sweet, into a front-line position of the utmost importance. A small island with a first-class harbour, already massively fortified, occupying the strategic choke-point between the two basins of the Mediterranean, astride key trade routes, Malta was an almost ideal possession for a maritime power in a global war. Unfortunately Orthodox Tsar Paul believed he was now the Grand Master of the Roman Catholic Knights of St John, and entitled to assume control of the island in their name. Both Nelson and Dundas had warned against this, while the final decision to exclude the Russians was greeted with relief by local commanders and the Maltese population. For Paul this was the last straw. He quickly manufactured an excuse to dismiss the British Ambassador, impound British merchant ships and sailors, and annex the smouldering Anglo-Danish trade dispute to revive the old Russian aim of excluding the British from the Baltic.

The Armed Neutrality convention, signed on 16 December 1800, made the minor powers cat’s paws for Russian Great Power policies. Russia did not share the maritime commercial interests of her Scandinavian clients: she sought control of the theatre, and a rapprochement, or worse, with France. The British had long recognised this strain in Russian policy. Consequently Denmark, Prussia and Sweden were coerced into following a Russian programme, which had at its heart the assertion of dominance over their countries, and the establishment of the Baltic as a Russian

mare

clausum

– a consistent aim of Russian policy since the days of Peter the Great.

3

The combination of challenges now posed by the Tsar made a rapid and resolute British response inevitable. He threatened Britain’s belligerent rights, the cornerstone of her strategy against France. Nelson

had long understood this connection. If the blockade could be flouted by neutral shipping the French could rebuild their fleet with Baltic naval supplies, and resume their economic rivalry with Britain, securing funds for further fleet-construction programmes. If Britain accepted the argument, she would abandon her great-power status, and accept French hegemony over Europe. It would also give the Tsar control over the naval stores that Britain required: a diplomatic lever of such power simply could not be left in his hands. These issues were fundamental to Britain’s very survival.

The powerful professional presence of St Vincent as First Lord of the Admiralty in Henry Addington’s new government was highly significant. His knowledge and determination ensured the Baltic fleet left on time, and was adequately supported.

Pitt made a powerful speech in the House of Commons on 2 February 1801, responding to the temporary Whig leader Charles Grey, in which he warned that if Britain resorted to force, she would have to ‘totally annihilate the foreign commerce and consequently the domestic industry of all those Countries who shall engage in such a Confederacy’. The British position would ‘never be relinquished … till Her Naval Power be annihilated.’

4

He also used the occasion to pour scorn on the unpatriotic and misguided views of the rump opposition, who had expressed doubts about the justice of the British claims against neutral vessels, and the importance of the issue.

5

Stressing this was an point ‘upon which not only our character, but our very existence as a maritime Power depends’, Pitt demonstrated the legal basis of the claim, and pointed up the bad faith of the Danes in abrogating the agreement of August 1800. He condemned the call to wait for more details of the new Treaty, in case the powers should ‘produce something like a substitute for the fallen navy of France’, or the carriage of stores to the French so that they could rebuild their own fleet. This was not the time to let slip the means by which the naval power of France had been destroyed – and the House agreed.

6

Having established the line of policy he thought appropriate, Pitt told the King that he would resign the following day. The time was ripe for change: with the failure of the Coalition the country was alone, and anxious for peace. An unprecedented rise in the price of bread sparked widespread disaffection, and there had been little glory to distract attention from the threat of French invasion, domestic unrest and high taxes. Fortunately for the country, the policy left in

place by Pitt would bear fruit before the time came for peace with France.

7

The formation of the Armed Neutrality threatened to have an early and serious impact on naval stores, especially hemp, which would ‘make it necessary to economise our stores as much as possible’. Spencer issued a Circular order to economise, anxious to get the fleet in good order for the spring ‘when it is not improbable that we may have a more extended naval war on our hands than we have ever yet had’.

8

St Vincent, meanwhile, was quick to recommend an admiral for the situation:

Should the Northern Powers continue their menacing posture, Sir Hyde Parker is the only man you have to face them. He is in possession of all the information obtained during the Russian armament [of 1791, when he was Hood’s chief of staff], more particularly that which relates to the navigation of the Great Belt; and the

Victory

will be a famous ship for him being by far the handiest I ever set my foot in, sailing remarkably fast and being of easy draft of water.

9

The recently expelled British Minister in St Petersburg, Lord Whit-worth, reported that the Russian fleet totalled forty-five battleships, but only seven or eight were in tolerably good order: some had broken backs, and the rest were hardly seaworthy, needing serious repairs.

10

By the New Year the issue had come to a head. Secretary for War Henry Dundas feared for the West Indies, and requested the Admiralty watch for Scandinavian ships leaving the Baltic.

11

The situation was complicated by a shift in the Russian position. For the Tsar, Malta was the key: after the Russians had been excluded from the occupation, he embargoed British shipping, and by December Bonaparte was flattering Paul, who was treating for peace with France. The Russian shift alarmed Denmark and Sweden, whose diplomats proposed a compromise settlement of the neutral rights issue, but Foreign Secretary Grenville was prepared to use force to uphold the British interpretation. To concede anything would be a sign of weakness that could not be afforded by a nation standing alone against France and relying on seapower for her security and success: ‘if we give way to them we may as well disarm our navy at once.’ On 16 December, Grenville declared that it was better to fight, and ‘though some temporary alarm will arise as to our commerce, we shall give more animation to the feelings of the Country, and go on, upon the whole, quite as easily as we should without it’.

12

This message was conveyed to the ministers of

the neutral courts at Berlin on 28 December 1800, and three days later the King’s speech at the opening of Parliament made the issue public:

If it shall become necessary to maintain against any combination, the honour and the independence of the British Empire, and those maritime rights and interests on which both our prosperity and our security must always essentially depend, I entertain no doubt either of the success of those means which, in such an event, I shall be enabled to exert, or of the determination of My Parliament and My People to afford Me a support proportioned to the importance of the interests which We have to maintain.

13

By then it was too late. The neutrals had signed a convention in St Petersburg on 16-17 December, and this was ratified in early January. Their action was confirmed in London on 13 January 1801 by the Danish minister. Britain had to respond vigorously. Secretary for War Henry Dundas reviewed the Cabinet papers, and sent his thoughts on the situation to the Admiralty. His view of the Baltic was conditioned by the wider problems of the war.

We must all agree that [we] have now the greatest stake to contend for that ever called forth the exertions of this country … the great trial of strength must be in the course of the ensuing summer, but that as to all Baltick operations the game is lost, which alone can make success certain, if we are not able to have a powerful fleet there the moment it is accessible, with the professed object of annihilating the confederacy of the North by the capture or destruction of the Danish Fleet.

He was well aware that the French armies were largely unemployed, and could be used to attack British interests anywhere in Europe; they might even be shipped to the Cape of Good Hope, the West Indies and Minorca. He called for a redistribution of naval forces to meet the danger. The French and Spanish battleships at Brest would be covered by St Vincent with sixteen three-deckers and eighteen seventy-fours, ‘leaving two eightys and ten seventy-fours for the service of the Baltick and the North Sea’. This would be enough, by early March,