Nelson: Britannia's God of War (57 page)

Read Nelson: Britannia's God of War Online

Authors: Andrew Lambert

He then compiled a codicil to his will, leaving his mistress, her claims made clear, and his illegitimate daughter as a legacy for the country to support. Blackwood and Hardy witnessed the paper, but it had no legal force, as he must have known.

Shortly after completing his prayers and promises Nelson was back on deck. By now it was obvious to everyone that the enemy were going to fight: their bold display required an answer. His thoughts were quick, and to the point. He would use the new talking telegraph to send a personal message to the fleet, the sort of morale-boosting encouragement he had given the crew of

Victory

earlier in the day by walking about the ship and chatting with the men as they prepared for battle. He asked signal lieutenant John Pasco to send the message that ‘England confides that every man will do his duty.’ The key word was ‘confides’, meaning ‘trusts’: he was not trying to make his men do their duty, but telling them that he had complete faith in them. Nor was England the real basis of the message – in the face of the enemy men need something more immediate, and more personal. The focus of their loyalty that day was nearer at hand, it was the embodiment of England at sea, the deity of the oceans. The meaning was ‘Nelson knows that every man will do his duty.’

Unfortunately ‘confides’ had not been reduced to a simple flag hoist in Popham’s code, and Pasco suggested substituting ‘expects’, which had. Nelson accepted this change, and the signal entered the record. Collingwood, who lacked the human insight and warmth to see the need, or the opportunity, grumbled that ‘We all know what we have to do.’ He was almost alone in such thoughts, and once he knew the message he changed his mind. Like everyone else Collingwood was struck, exactly as had been intended, by the very personal message, one that touched the heart of every man in the fleet, and gave them a share of the divine magic that only Nelson could bring to the situation. As the message was relayed from the signal officers to the crew, ship after ship burst out in ringing cheers of approval. Nelson followed the message with two signals from the old book: ‘Prepare to Anchor’ and, as ever, No.16, ‘Engage the Enemy more Closely.’ He would send no more.

Blackwood had been on board the

Victory

with Captain Prowse of the

Sirius

from early in the day, their ships running alongside the line. They would carry any last signals for the fleet, and as they were not involved in the fighting, could watch the battle develop. It was typical of Nelson that when fortune threw the hero of the

Guillaume

Tell

action back into his fleet, he was on the most intimate terms with him again in a matter of hours, having absolute confidence in his seamanship, judgement and instinct. However, Blackwood could not get Nelson out of the flagship, nor the flagship out of the lead. Nelson knew the value of his leadership: he had given the men a morale-boosting message, now he would set them a morale-boosting example. In the days and months that followed, the conversations of Blackwood, Hardy, Alexander Scott and Doctor William Beatty were written out in a manner that suggested that Nelson could have avoided an obvious threat. They represented the admiral’s actions as little more than bravado, and give no other purpose to his staying on his flagship, or wearing his own coat.

But there was no bravado about Nelson in battle. He had a deadly serious purpose in mind, and would not give anyone else the honour or the responsibility of winning the battle at a blow. He had to lead the line, and destroy the enemy flagship. Nor would he take off his coat, which he always wore. It is unlikely he even owned a plain uniform coat, and in any case, to hide from the enemy would be disgraceful. Collingwood was already setting a magnificent example, and it was unthinkable that Nelson should leave his ship, his post of honour or even shift his coat. After all men worshipped Nelson, the hero of a hundred fights, because he shared the dangers with them. How would the men of

Victory

have felt if he had left them at the last moment? What would the country have said if the battle turned out to be another ‘Lord Howe victory’ while Nelson watched at a safe distance?

Such speculation is unnecessary, for it is based on the wholly erroneous idea that Nelson entered battle with a death wish. This Victorian legend dealt with his ‘shameful’ private life by arguing that he knew that he was living an immoral life, and wished to expiate his crime through a glorious death. It is, like much more of the Victorian Nelson, utter nonsense. Nelson did not go into battle seeking a glorious death as the ultimate finale to his career. Though the idea had occurred to him at a particular time – the turmoil of his private life in late 1800, when he spoke to West at Fonthill, made such a death seem attractive – this mood soon passed. His life had changed by 1805, and he was only too aware of the public fame and private comfort that would await him on his return from another glorious battle. He was already immortal, and had no need of his Wolfe moment. Wolfe was an unknown who achieved fame by the manner of his death; Nelson had become a national deity in life, a hero in the Homeric mould. He was too great to need death as the final distinguishing mark. He acted as he did on 21 October 1805 because it was his duty. He had to lead: the battle could not be controlled from anywhere else. It is highly significant that in the hour before contact he twice changed the attack plan for his line, which he could not have done from anywhere else. By 1805, death in battle was an occupational hazard for Nelson, not an object.

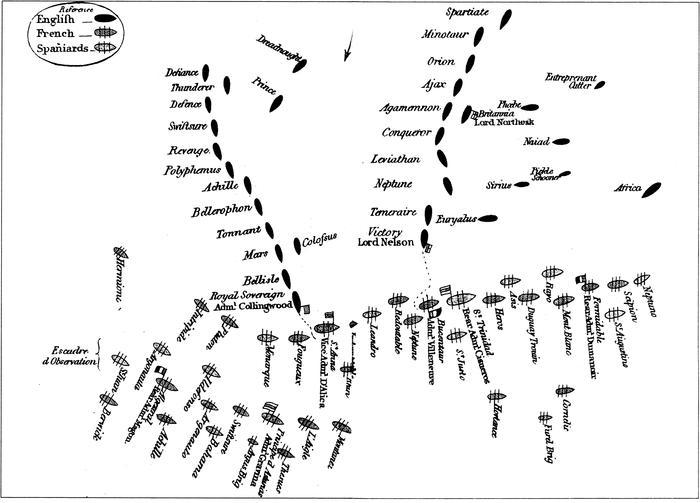

The battle of Trafalgar (from J. Corbett,

The Campaign of Trafalgar

, 1910 Positions shown are at the start of the battle on the morning of 21 October.

With the enemy waiting for his attack, Nelson held on in line ahead, to keep the ultimate point of attack uncertain; this would ensure the enemy could not counter his attack by reversing the van squadron. The two British lines appeared to be on slightly converging courses, while a shift in the wind left the Franco-Spanish force (the ships deliberately intermixed rather than in national formations) sagging in the centre, presenting a concave formation. Nelson aimed for the fourteenth ship in the enemy line, the target given in the memorandum, which was two ships behind Villeneuve’s

Bucentaure

. However, the French admiral had not shown his flag, making the ship ahead of him, the massive

Santissima

Trinidad

, an obvious target. Misleadingly informed that the enemy admiral was in a frigate, Nelson shifted his plan to cutting through the enemy van, and preventing it from getting into Cadiz, exploiting an opening that had suddenly appeared in the enemy line. Then, as the enemy rear opened fire on Collingwood, Villeneuve and his admirals displayed their flags. Nelson immediately headed for the bow of the enemy flagship; Villeneuve parried by closing on the stern of the

Santissima

Trinidad

. Nelson simply shifted one place down the line, and went under the Frenchman’s stern, despite a brave attempt by the

Redoutable

to close down the gap.

When the enemy opened fire on

Victory

shortly before midday, it was time for Blackwood to leave. As he climbed down the side of the ship, Blackwood tried to sound cheerful, trusting he would return that afternoon to find Nelson had taken the twenty ships he considered a good result. Without hesitation, Nelson cut him cold: ‘God bless you, Blackwood: I shall never speak to you again.’ It was a terrible send-off

for a devoted follower, and quite out of character. These were not the final words of a man anxious to die, but of a man who knew that he would be surrounded by death within a few minutes.

Events bore out Nelson’s analysis. As

Victory

closed on the enemy fleet, several ships were able to fire on her, mostly aiming into her rigging, trying to cripple her forward motion, while she was unable to present a gun for almost half an hour as she passed through the last eight hundred yards. This was the hardest part: to keep calm and endure a beating without the comfort of firing back. Within minutes, round shot were smashing through the flimsy bow of the ship, and the unprotected men on the upper deck. The first to fall was John Scott, Nelson’s Public Secretary, who had been standing on the quarter-decktalking with Hardy when a ball cut him in two. As his mangled remains were heaved overboard, Nelson lamented the passing of a close friend. Soon after, the great ship’s wheel was smashed to atoms, and the ship had to be steered from below decks, with commands relayed by voice. Then a double-headed shot, intended to cripple the rigging, scythed down a file of eight marines on the poop; Nelson quickly ordered Captain Adair to disperse his men, to avoid further heavy losses. Still Nelson and Hardy paced up and down on their chosen ground, the starboard side of the quarter-deck, not a foot from the smashed wheel, with splinters flying around them. One hit Hardy’s shoe, tearing off the buckle. Once he was sure Hardy was not hurt, Nelson observed: ‘This is too warm work to last for long.’ He was right: fifty men had been killed or wounded, and they had yet to open fire. No wonder Nelson was impressed by the cool courage of

Victory

’s crew.

By 12.35 the concavity of the enemy line allowed

Victory

’s lower-deck guns to open fire on both sides as they closed, shrouding the ship in smoke, and providing some relief from the torment of waiting. Soon afterwards, she ran under the stern of the French flagship. The first gun to fire was the massive sixty-eight-pounder carronade on the port forecastle, blasting an eight-inch diameter solid iron shot and a case filled with five hundred musket balls through the flimsy stern galleries of the

Bucentaure

, followed by every one of the fifty broadside guns. The French ship shuddered under the impact of a hundred projectiles from the double-shotted broadside. Over two hundred of her officers and men were killed or wounded: Villeneuve was the only man left standing on the quarter-deck, and twenty of her eighty-four guns had

been smashed out of their carriages. From inside the allied line, the French

Neptune

raked

Victory

and the

Redoutable

blocked her passage through the formation. Nelson’s attempt to cut the enemy in two had ended with his ship trapped in the middle of the Combined Fleet, fighting on three sides. Unable to get through, Hardy asked which ship he should run into – Nelson left the choice to him. Hardy chose the

Redoutable

. Nelson would have preferred to keep his ship mobile, but there was nothing else he could do. Villeneuve’s formation and the lack of wind had forced him to pile into a group of ships, not cut through a well-ordered line.

Once

Victory

had crashed into the

Redoutable

, Nelson was immobilised: he had sacrificed choice and tactics for all-out assault. While it was a significant modification of his memorandum, his overall concept survived. The impact of his line, headed by three three-decked ships, stunned Villeneuve, while the devastating raking fire they poured into his stern left him trapped on a crippled ship – immobile, unable to fight, signal, or escape. The allied centre was reduced to a collection of individual ships, and while they would fight with remarkable bravery they lacked the leadership and skill to meet the impact of the impetuous, irresistible British ships. Each British ship was, in itself, a superior force to an enemy of equal size and firepower. At close quarters the speed and regularity of British fire would overwhelm the allies, not immediately, but cumulatively. In the space of three hours the Franco-Spanish force collapsed, destroyed by gunnery the like of which had never been seen before. Nelson’s attack had broken all the rules of tactics, treating a fleet in line waiting for a fight like one running away, substituting speed for mass, precision for weight, and accepting impossible odds.

Collingwood had picked out one of the Spanish flagships, the three-decker

Santa

Anna

,

raked her as he broke through the line, and ran alongside opening a furious battle that took over two hours to resolve. He fought alone for ten to twenty minutes, surrounded by enemy vessels, and even when the first group of his supporters arrived they too were soon fighting a far greater number of enemy ships. They survived and won the day because they hammered each of their attackers in turn, and by the time their performance was beginning to fall off the laggards came up and administered the

coup

de

grâce

. Big three-deckers like the

Prince

,

Britannia

and

Dreadnought

were the ideal answer to any Franco-Spanish rally. In fact the battle was won while the

enemy had far more ships in the fight than the British: the real triumph was not one of twenty-seven against thirty-three, but twelve against twenty-two.

British casualties tell the story. Twelve ships fought the decisive phase of the battle, while those that followed them in profited from their work. Of those first twelve, the numbers of deaths were as follows:

Victory

132;

Royal

Sovereign

141;

Temeraire

123;

Neptune

44;

Mars

98;

Tonnant

76;

Bellerophon

150;

Revenge

79;

Africa

62;

Colossus

200;

Achille

72;

Defiance

70.