Not Dead & Not For Sale (14 page)

Read Not Dead & Not For Sale Online

Authors: Scott Weiland

I

WENT BACK TO REHAB

but rehab didn’t work. That’s when Duff started talking about his trainer in Lake Chelan, Washington State. “Bring your detox meds and come up there with me,” Duff offered. “You’ll meet my martial arts master, one guy who can really help you.”

His help came quickly and powerfully. His name is Sifu Joseph Simonet, and he’s a master of six different martial arts forms. I planned to stay a month but stayed for three. At his Wind and Rock training facility, I also worked with his associate and fiancée at the time, Addy Hernandez, a kickboxer and holder of a black belt in kenpo karate. Sifu Simonet comes from a kung fu background in addition to the art form of Pentjak Silat Tongkat Serak. He created his own form called Key Fighting Concepts and, from day one, I related to his energy. He’s a deeply wise man with a bit of a temper and a flair for martial arts instruction and philosophical riffing.

“My art form never stops evolving,” he likes to say. “I can never repeat myself because the past is gone and the present is ever new, ever changing.”

With intense daily training, I learned to channel my aggression, confusion, fear, and athleticism in positive directions. The rigorous routine allowed me to wean myself off opiates. The setting also helped. Lake Chelan Valley sits in the center of the magnificent North Cascades National Forest. The lake is a breathtakingly beautiful fifty-mile, glacierfed body of crystal-clean water. Nature is untamed. Bears and wild goats roam the mountains. I fell in love with the area and decided to buy land there and, in time, build a cabin in the woods.

Back in Los Angeles, I hooked up with Benny “the Jet” Urquidez, a five-time world-champion kickboxer. Benny boasts that he has never been defeated, and when you train with him, you don’t doubt it. He was my instructor for eighteen months after I returned from Lake Chelan. This was a difficult period—around 2006—because Mary and I were still doing a death dance around our marriage. I’d walk into Benny’s dojo—his karate gym—and right away Benny could read my mind.

“You’re depressed,” he’d say. “The energy between you and your wife has turned especially toxic this week.”

“How do you know that?”

“I’m looking in your eyes—that’s how.”

Then Benny would start to explain the concept of being “glazed.” He said that obviously anyone can incur physical injury. But once you’re glazed, you’re mentally and spiritually protected from harm. The glaze resists negative thoughts. Of course, like everyone, you will be affected by external circumstances, feelings, and moods, but the impact will be minimal because of the strength of your spiritual and mental muscles.

Glazed.

Ready to walk back into the world a whole man, ready to accept the world on its own terms.

Ready to get out there, join up with a balls-out rock band, and reinvent myself as a singer and artist.

It was going to work.

It had to work.

It did.

And then it didn’t.

B

ACK IN

2003, after I joined Velvet Revolver and got straight, I wrote all the lyrics and all of the melodies for our first album,

Contraband

, which wound up selling over four million copies. The big hit was “Fall to Pieces.” Duff and I wrote it at Lavish, the studio I built in Burbank. It was built on a riff by Slash, and somehow in the middle of the night we turned it into a song about coming to terms—or not coming to terms—with my heroin addiction. It was also about my relationship with Mary, and how it was falling apart. When Mary wrote her memoir last year, she titled it

Fall to Pieces

. In the song, I sang …

All the years I’ve tried

With more to go

Will the memories die?

I’m waiting

Will I find you?

Can I find you?

We’re falling down

I’m falling

WE WENT ON THE ROAD

for two years, toured the world, and established ourselves as a premier rock band. Velvet Revolver was a powerful force. There was so much energy on that stage that at times it felt absolutely combustible. Anything could happen at any time. We were a bunch of renegades held together by a rough passion that none of us completely understood. We were dangerous. We were on a runaway train, and audiences were drawn to our breakneck speed.

I liked our first record but can’t call it the music of my soul. There was a certain commercial calculation behind it. We wanted hits; we wanted to prove that, independent of Guns N’ Roses and STP, we could make a big splash. And we did. My fellow STPers—Robert, Dean, and Eric—tried a number of musical configurations without me, but none of them were successful. I wished them well, but I have to confess that, as a competitive guy, I wasn’t displeased to be in a new band that fans were flocking to see.

W

HERE DOES IT COME FROM? WHAT IS IT?

I’m a tenacious drug addict. I give it up and I don’t give it up. I put it down and I pick it up.

But I’m also a tenacious recoverer. I never quit trying to quit. That counts for something.

In the middle of all this, I’m a tenacious writer and performer. I need to compose; I need to sing; I need the feedback from real people. I’m tenacious not only about making art, but I also refuse to abandon my career.

I tenaciously cling to the notion that demonic forces are at work when we surrender our will to the world of drugs. I especially think that’s true of cocaine. Cocaine—especially cooked-up, freebase crack cocaine—is downright evil.

I’ve had a series of cocaine encounters that have frightened me to death. At certain times, I’ve had to go back to my Catholic roots and recite prayers similar to those used by exorcists. But the negative forces were so powerful that I was unable to speak the holy words.

This has happened twice. The first time was in the late nineties; the second when I relapsed while playing with Velvet Revolver. In both instances, the dark presences made themselves known physically. There was stomping; there were actual forms facing me, the faces of skeletons. Otis, my golden retriever, bolted the room. He experienced what I experienced, saw what I saw, feared what I feared. I ran to the bathroom, locked myself inside, looked under the door and saw feet, saw shoes, heard voices, shook, shivered, prayed, tried to breathe, waited until the feet walked away and the noise stopped. I thought about what is perhaps the biggest question of man—is there life beyond this mortal coil?—and knew then that the answer is yes.

My belief is that the coke I was ingesting activated a paranormal force. That force once took the form of a minitornado, a whirlwind of tremendous energy that came after me and smashed against the side of the house, doing tangible damage.

Heroin is obviously intoxicating. Heroin kills all pain. Heroin kills the heroin addict. In my 1965 Ford Mustang, I’d drive to my heroin dealer, fix, and float out on a cloud. I’d float over Silver Lake Boulevard like the Goodyear blimp floating over the Rose Bowl on New Year’s Day. The heroin high is the jet stream without turbulence—that is, until the jet explodes and crashes into the sea. The coke high, while wildly stimulating, is a roller-coaster ride through hell.

A

S MY LIFE WENT ON,

my dad seemed to grow even more distant. As I was successful with music and unsuccessful with treating my addictions, I couldn’t connect with my father. He would disappear for long periods of time, not answer my calls, ignore my attempts to get closer to him. That changed in 2003, though, when during a rehab stay he accepted my invitation to attend family week. That meant the world to me. He participated in therapy sessions and, for the first time, he appeared vulnerable and willing to listen to my confused feelings about him. After several heart-to-heart talks, he turned to me and said, “You know, Scott, as a father, I’ve failed you. So instead of trying to be a father, why don’t I just try and be your friend. I think I can do that.”

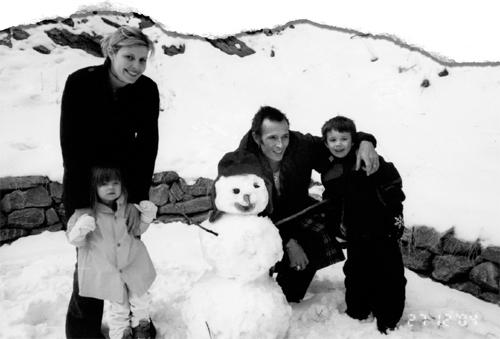

I was more than willing. Once out of rehab, I decided to have a weeklong Christmas celebration in my log house in the woods above Lake Chelan in Washington State. It was a male-bonding, multigenerational affair. I had my son, Noah; my dad, Kent; my brother, Michael; and my half brothers Seth and Matt, the boys Kent had with Martha. We bonded like a real family, riding snowmobiles, decorating the Christmas tree, exchanging presents, telling stories, and singing songs before the roaring fire. At night the winter sky was alight with a million stars. By day the world was a frozen wonderland. Michael seemed at peace. So did my dad. My son stayed by my side. I grew closer to Matt and Seth. It was beautiful.

And then it was over.

Michael went back into his dark world. My dad asked if his son Matt could work as my assistant. I agreed, but Matt, understandably, didn’t love the job and never took it seriously. I had to let him go. I don’t think that helped my relationship with my father. I called him, but he never called back. Months passed. Once again he disappeared. When he did call, he reached out to Mary when he heard that she and I were divorcing. He felt obliged to comfort her, not me.

Christmas time in Colorado at Mom and Dad’s. Noah and Lucy’s first snowman.

DO’S AND DON’T’S

Do love horses on trails.

Don’t like motorcycles on the L.A. Fwy.

Do love escargot (since I was five).

Don’t like fast food.

Do love winter and snow.

Don’t like hot winter days.

Do love the mountains.

Don’t like pretentious cities.

Do love an open heart.

Don’t like dating.

Do love good sheets and a nicer hotel room.

Don’t love to tour too long.

Do love our president.

Don’t love a certain former governor of Alaska—who does anymore?

Do like dressing well, as if you haven’t put any effort into it.

Don’t like men that dress like cads.

Michael, in light, brighter days. I miss those days.