Not Dead & Not For Sale (15 page)

Read Not Dead & Not For Sale Online

Authors: Scott Weiland

I

N 2007, I WAS AT HOME WITH THE KIDS.

Mary was at Sundance, throwing parties for stars and socialites. The call came early in the day. It was a female friend of Michael’s. She could hardly talk.

“Scott … Scott … oh my God …” she said. “I don’t know how to say this. I’m at Michael’s apartment and he’s … he’s gone.”

“What do you mean ‘gone’?” I asked.

“Michael’s dead, Scott. He’s dead. I don’t know what to do … you’ve gotta come over here to identify his body. You’re next of kin.”

I went cold.

Seconds later, a burning hot sweat broke over me. I felt the vile, sour taste of vomit in my throat. From the pit of my soul, the same soul that was entwined with Michael’s, this guttural wail … “No! No! No! No!”

The first thing I did was go to the liquor cabinet, fill a glass with whiskey, and drink it down. As an ex-junkie, my animal sense kicked in. I put on my emotional armor. I left the kids with the nanny and took off for Michael’s apartment in Silver Lake.

While driving over, my head flooded with memories. I remembered as kids how Michael believed in Santa and Santa’s elves. I’d dress up as an elf and run around the woods in back of our house. Then my parents, willing accomplices, would tell Michael to go look. He was completely fooled. Up to his early twenties, he still thought it was real, until it was casually mentioned one year over Christmas dinner. My brother had a delicate yet very old soul.

Only a month ago Michael had been happy for the first time in years. He was off dope, off crack. It felt like all our past troubles were behind us. He and his wife were on good terms and he was about to be granted visitation rights to his wonderful little girls.

Then his mirror image of himself snapped. For all the love in Michael’s heart for his family and friends, he had none for himself. He weighed 180 pounds, but had only ten pounds of faith in himself. Maybe that’s why they say that when you die, your shell loses ten pounds.

At some point during the drive over, I called Mary. She started wailing. This was unbelievably tragic, unbelievably sad. Out of instinct, I called Benny “the Jet” Urquidez, my sensei.

“What!” he screamed. “I lost my sister today!”

The ruthless law of mortality.

The horrible reality hit me between the eyes when I arrived at Michael’s apartment. The police were there along with some of his friends. The place was chaos—piles of dirty dishes, broken plates, dust, the stink of filthy clothes, the smell of death. I walked to Michael’s bed. He was stretched out; he seemed comfortable; his eyes were closed. It looked like him but it didn’t

feel

like him.

A note was taped to his refrigerator, referring to his little girls: “Live for Sophia and Claudette.” Was it a suicide note, or was it written in an inspired moment to remind himself of what he had to live for? I’ll never know.

His heart gave out. Drugs, sure, but Michael died of a broken heart. That day a big part of me died as well.

Later we learned that it was cardiomyopathy, a disease of the heart muscle that four years earlier had been diagnosed by Dr. Drew Pinsky for me, not Michael, when I was in the throes of heroin detox.

Why Michael and not me?

Why was I always able to pick myself up off the ground and muddle through? Why didn’t Michael have that ability?

There’s a line in a Nirvana song that goes, “I miss the comfort of being sad.”

That was Michael, but never me. Yet now I do feel that comfort of being sad. I miss the comfort of feeling anything.

Emptiness.

Loss.

A brother gone.

All this happened when we were making the second Velvet Revolver record,

Libertad

.

The brother of Matt Sorum, the Velvet Revolver drummer, also died during that same period.

We were left alone, haunted by questions of what we might have done, what we could have done, what we didn’t do.

In a song on that record called “For a Brother” I wrote:

Could and should have been

And didn’t

I’ve given up my hand for a brother

Given up a hand for free

I’ve risen and forgiven and I’ve pardoned

But you set yourself free

That word—freedom,

libertad

.

Another song on

Libertad

, “The Last Fight”:

Break the chains of featherweights and giants

With disdain for everlasting lives!

They’ll refrain when we spit out the fire

And start living

IN THE WAKE OF MICHAEL’S TRAGIC DEATH,

things got worse with me and Mary. We started binge drinking. Our nanny would watch the kids; we’d go out for dinner, get plastered, and come home and have great sex. There were other times, however, when Mary showed no interest in drinking and sex at all. I could never tell. It was always a flip of a coin. Her mood swings, combined with my mood swings, could flip us in any direction. For

Libertad

, I wrote a song I couldn’t call anything but “Mary, Mary.”

Mary, Mary by my side

Atomic love the kind you cannot buy

Black boots, strong legs, got style

My baby knows the walk, you see her come from miles

Modern lover, modern kind

When we close the door, we’re never out of time

Mary, Mary on my mind

… want to find out what you’re saying

Want to play the games you’re playing

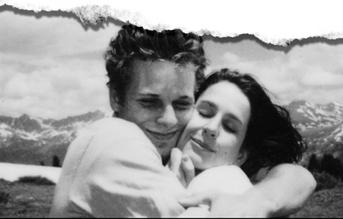

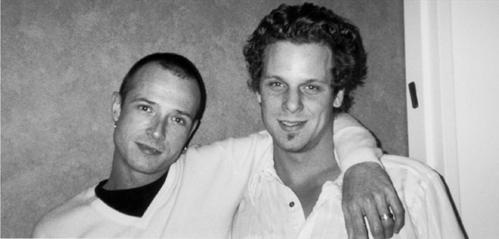

Michael, alone

Michael with his wife

Me and Michael

I

WAS RUNNING WILD

during the second Velvet Revolver tour. At the beginning of the tour, I was okay, but then a single line of coke in England did the trick. I snorted it. And soon the demons were back. Thus began another decline. That was 2007.

With my “Mary, Mary” obsession pulling me apart, and the grief from losing my brother breaking my heart, this little line of cocaine looked good. For me it was the same as stepping in quicksand. Before long, I was smoking the shit. After years of not doing street drugs—of not doing

any

kind of drugs—I was out there again, going to dangerous places to buy substances. All this was done in secret; the other guys in Velvet Revolver—all of whom except one, by the way, had suffered their own slips since the band formed—didn’t know I was using.

Only my manager, Dana Dufine, knew of my decision to go into rehab. I had to. I couldn’t live with myself; couldn’t stomach the cold fact that I was back on the fuckin’ pipe, doing what I had sworn I would never do again. When I told the guys that we’d have to miss a couple of gigs because I needed treatment, their reaction shocked me. They told me I’d have to pay them for those cancellations—in full. I reminded some of them that when they had relapsed and needed rehab, I had supported them completely. It made no difference to them. They wanted compensation from me, but this time, no deal. Fuck me once, shame me twice … well, just fuck off.

There had been other Velvet Revolver problems. Slash’s wife, Perla, had inserted herself into the band business to the point of participating in band meetings. Beyond that, Velvet Revolver was essentially a manufactured product. For all our hits—“Fall to Pieces,” “Slither,” “Set Me Free”—we came together out of necessity, not artistic purpose.

The breaking point came when, after the tour for

Libertad

started up again, Matt wrote scathing things about me on the Internet. Our fragile brotherhood was permanently smashed. From a stage in England I told the crowd—along with my fellow bandmates—that they were witnessing a special event, Velvet Revolver’s last tour. It didn’t matter that Velvet Revolver had sold some five or six million records. I was out.