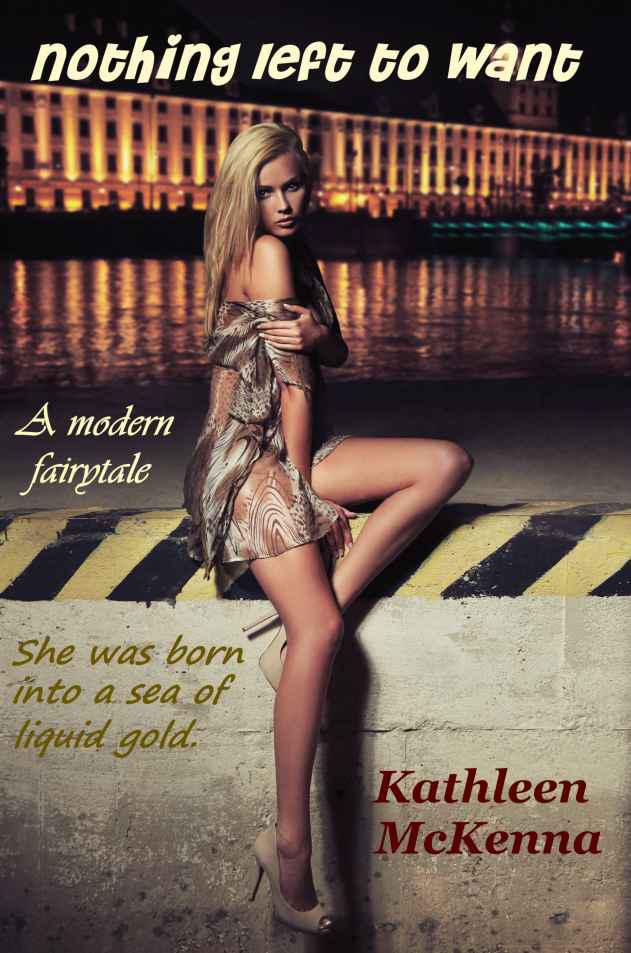

Nothing Left To Want

Read Nothing Left To Want Online

Authors: Kathleen McKenna

NOTHING LEFT TO WANT

A modern fairytale

by

Kathleen McKenna

ISBN 1469906996

EAN 978-1469906997

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

'Nothing Left To Want' is published by Nothing But Publishing Ltd, a UK-registered private limited company.

'Nothing Left To Want' is the copyright of the author, Kathleen McKenna, 2012. All rights are reserved.

All characterizations of people in this story are fictional and any likeness to any person living or dead is entirely accidental.

Chapter 1

I came here to the guest house to hide from the sounds of the rats; they scare me. It hasn’t helped much because now I can hear the horrible plunk, splash sounds they make when they go into the pool. Maybe they are thirsty; even the toilet bowls have dried up. There is no water, no electricity and no heat, for them … or me.

I am so cold and so frightened. I think I am going to die and I don’t want to die. I don’t know how to save myself and this time no one else is going to come and save me. No one alive cares about me.

My name is Carolyn - it’s a derivative of Carolina. When I was born my father bought his first football team to celebrate his first child. He paid half a billion dollars for the team and he told the stunned sports and financial worlds that it wasn’t worth ‘one hair on my little girl’s head, not that she has any hair yet'. I imagine that they all laughed sycophantically and went home and shook their heads in disgust. I get a lot of that. It's how people always react to my family’s name and to their money.

Seven eight years ago a reporter from Page Six followed me into the bathroom at a club - I don’t know which one - and she stared at me while I stared at myself in the mirror. I didn’t know what she wanted, I didn’t know what to say, I never know what to say to anyone. It's one of the things people like to say about me. Finally, because her gaze made me so uncomfortable, I laughed a little and asked her if she thought I should get Botox for my forehead. I was nineteen. She took it seriously. I think that is so creepy. Why would anyone take a question like that seriously, take me seriously for that matter. After the reporter gave my stupid question a lot more thought than it deserved, she said, “I think you can wait for a year or two, so, hey, what else are you up to, Carey?” I felt grateful to her for telling me I didn’t need Botox yet, I wanted to reward her, give her something personal she could use in her article on me, but there’s not too much about me personally that is interesting or at least there wasn’t then.

I shyly revealed that I liked Doritos. She nodded, smiling, pleased, and the funniest or worst thing about the whole meaningless encounter was that the next day I read a story about myself. “Carey Kelleher is a real live girl just like the rest of us and she confided in this writer exclusively that she likes to sneak a Nacho Cheese Dorito now and then.”

I’m so tired but I think if I could get up one more time, I would reach for my cell phone and dial a number. It’s one I haven’t called in so long.

Mother, Mom, Mama … help me.

Is that what I would say if I could stand up and make it over to the dresser? My cell phone is the last line with who I was, both literally and figuratively. When I left treatment in July, they - they being my parents - told me through intermediaries not to contact them unless I was going to return. Our family lawyer, Herbert, once Uncle Herbert, now only Herbert, sternly informed me that “all monies will cease immediately. You must understand, Carolyn, that your parents are united in this decision.”

I laughed in his face. I told him that was a switch, them being united and then I told him to tell them I said to go fuck themselves and their money.

Tomorrow is New Year’s Eve. I don’t think I’ll be very aware of it by then; I don’t think I’ll be alive for it. But whatever … what am I missing anyway, another party, another scene, another load of paparazzi?

“

Carolyn, Carey, look over here … Hey, Carey.”

I wouldn’t be afraid to die if I just had some idea of what it’s like. Even though I’ve met so many people, every kind of person, I’ve never met a dead person. Can I go to heaven and everyone there will want me again, or is it like now, where nobody wants me and it’s getting too dark to see? I’m not sure what’s real and what isn’t. Will I spin out into nothing, terrified and alone, crying for someone to help me, to make it stop, to make it better? If that’s what it is, it will only be more of the same, and I am frightened of more of the same. I’m ready for different and for less now. I heard once that death is going home but where is home for me?

I can feel something against my leg but I can’t kick it off.

Mama, make it stop.

I guess a lot of people are going to write about my death and I don’t think there is anything I can do about it, but I wish no one ever had to know that I died here in this ruined place, a ruined girl, a girl who had a rat nibbling on her cooling skin and who was crying out for her mother. Of all the people I could call who wouldn’t show, she would head the list, so how pathetic am I?

I hope that she doesn’t find out I still wanted her.

* * *

A hundred billion years ago when I was a little girl, I used to wake up at night sometimes from bad dreams. I don’t know why I had bad dreams then … maybe I was dreaming of my future; that would scare any kid.

No matter how late it was, though, or how hard I cried, it was never her, my mother, who came to me at night.

I wasn’t left alone to scream in the dark, there was always someone around who was paid to love me, and I don’t know why I couldn’t get that through my thick skull, why I refused to understand that the only ones who would ever be around to love me would have to be paid for it. I didn’t, I wouldn’t, give up though. I kept calling for her over the shoulder of whichever nanny or maid was comforting me.

She never came then, and she won’t come now.

Part 2

Golden Girl

Chapter 2

My sisters and I were raised to never use the words 'I want'. It wasn’t that our parents didn’t know that we would naturally want things; it was stressed to us that while it was okay to want things, it was simply not okay to say it aloud.

What

was

okay was to say, “I will have that.”

I don’t know why I could never stop being annoyed over such a simple distinction. I thought it was petty and stupid. Maybe that’s why, in retaliation, I learned early to say, 'I will have those' instead. I waited for restraint that did not come, or for my parents to notice that though I wanted for nothing, I was still taking everything.

I didn’t like being told not to want things. Automatically it made me desire things fiercely, but I may have expected that someone, anyone, would step in and tell me to at least cut down on having so many things, to calm down about acquiring things, buying things, buying everything - but nobody said a word.

It’s a typical loser's cliché to say that I wanted things that I would never have, like being the center of my parents' hearts, or believing even for an hour that I was good enough, beautiful enough or special enough to belong to a family like mine. Yet, like a lot of eye-rolling clichés, it’s also true.

Poor little rich girl, money doesn’t buy happiness, money can’t buy you love, starving at a banquet

, they aren’t just sayings. Oh well, I mean they are sayings, obviously, but it’s because someone before I came along actually did say them, lived them, lived like me. I’m guessing from the depressing nature of those statements that they figured out pretty early on that being rich isn’t for people with weak stomachs, or weak investment portfolios either. The latter is never an issue in my family, it’s the former that will bust you up on the rocks. My short life story, for example, I am guessing is going to turn into a world class cautionary tale. By the age of nine or so I gave up showing that I wanted those silly sentimental things and began to focus very seriously on getting the things I could have, which worked out fine. I quickly learned that what I could have was pretty much everything.

* * *

In the beginning there were the Kellehers, and that is my family. We are considered old money. Here in America, old money means it’s over fifty years old, and we have been rich, really rich, unimaginably rich, people would say 'filthy rich', for three times that long. We aren’t famous in a tacky new money entertainment way, though our last name is a household word in a very literal sense, but people don’t, or I should say didn’t, recognize us as individuals until I made us famous.

There is almost no one alive who hasn’t added to my family’s money. If there is a headache, or depression or a surgery going on anywhere in the world, then it’s a good bet that a Kelleher Pharmaceutical is being used to make someone feel better, or to make someone unconscious, which is usually the same thing.

The genius of my great-great grandfather is that he understood even before people did themselves that they were going to need pharmaceuticals to help them get through their lives. My family’s drugs do that and the money rolled in like water down a fall, creating an American dynasty built on human pain. All-in-all that is a pretty fair analogy for my life story.

My father, Kells, is the direct descendant of the first John Kelleher, also called Kells. There is always only one Kells Kelleher and, like a king in the old storybooks, all gifts and punishments rain down from the current Kells.

My cousins are descended from another Kelleher, David Kelleher. He was a wild man even by standards in my family, and that is saying something. When he was in his eighties, he married a twenty year old non-English-speaking Latino maid and left her nearly all of his three billion dollar fortune. His heirs have since been forced to live out their lives on the remainders of their trusts. Even the richest amongst them is only worth seven hundred million or so to this day. We call them the poor relations. It’s a little inside family joke but really I think they agree with it, as do those of us on the Kells Kelleher side.

In my family money is no laughing matter.

Since my father is a direct line Kells, we are all much richer or will be, or might be, as Daddy, the ruling Kells, decides. My father’s net worth, his personal fortune, is estimated at a conservative fifty billion dollars.

That is just cash and holdings because he still retains a third of the publicly held stock of Kelleher Pharmaceuticals, and as long as people remain in pain, the money will never stop. Most people don't think about families like mine. When they think about money, they think of the Sultan of Brunei or Bill Gates, even Donald Trump. But they forget that every time they pop a pill, or pump their gas, or eat a bowl of cereal, that some living person somewhere must have invented it and that daily, all across the world, all the people using these ordinary things are giving more money to families like mine.

* * *

I was born at our family’s Palm Beach compound. It’s called Kelleher’s Rest. In the family we just refer to it as 'The Rest'.

The main house all fifty thousand feet of it, sits perched upon a man-made hill looking out over the ocean, surrounded by one mile of private fenced and patrolled grounds. When I was really little, I thought my father also owned the ocean which is not as wild as it sounds because he does own most of the beach and you can't have an ocean without a beach, just like you cant have envy if there is no one better off than you. My father, who had graduated from Brown University a few years before with a useless degree in Art History, met my beautiful mother at a party in SoHo. At the time he decided to marry her, he believed that they would be happiest living at The Rest, where he could indulge his passion for painting bad seascapes that he never allowed anyone to see. It was assumed, with so many pleasures available to her, that my mother would develop passions of her own to fill her days until she gave birth to the next Kells, at which time she would become a devoted mother by carefully overseeing the selection of staff and furnishings for the nursery.