On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (18 page)

Read On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears Online

Authors: Stephen T. Asma

One of the most impressive aspects of the character of Beowulf is his embodiment of what Tolkien calls “Northern courage.” Beowulf embodies a “theory of courage” that puts the “unyielding will” at the center of heroic narrative. The Norse imagination, filled with the philosophy of absolute resistance, was properly tamed in England, according to Tolkien, by contact with Christianity. The Viking commitment to “martial heroism as its own end” is unmasked by Christianity as mere hopeless nihilism, something to be overcome and remedied. Tolkien says that the poet of

Beowulf

saw clearly that “the wages of heroism is death.” The Christian looks back over the course of pagan history and finds that all the glory won by heroes and kings and warriors is for naught, because it is only of this earthly temporal world.

Without Christianity, monster killers are either hopeless existential heroes, trying by pathetic human effort to rid the world of evil, or they are themselves monstrous giants amid a flock of righteous and meek devotees. Hercules, for example, is judged by medieval Christians as an abomination

to be dethroned from his traditional place of adulation. The medievalist Andy Orchard quotes Aelfric’s tenth-century

Lives of the Saints

, which asks, “What holiness was in that hateful Hercules, the huge giant, who slaughtered all his neighbors, and burned himself alive in the fire, after he had killed men, and the lion, and the great serpent?”

7

Alexander the Great’s ancient heroism was also reconfigured in the medieval era. He courageously kills monsters in the

Alexander Romance

but is also regularly humbled by wise sages who point out his prideful ambition. In the medieval story of Alexander’s

Journey to Paradise

he is given a Judeo-Christian lesson in humility. After being surprised by a small mystical jewel that outweighs hundreds of gold coins, he is told by “a very aged Jew named Papas” that the jewel is a supernatural gift. The disembodied spirits who are waiting for Judgment Day (when they will get their bodies back) have offered this jewel to Alexander. Papas tells Alexander, “These spirits, who are enthusiastic for human salvation, sent you this stone as a memento of your blessed fortune, both to protect you and to constrain the inordinate and inappropriate urgings of your ambition.” “You are oppressed,” he continues, “with want, nothing is enough for you.” After more criticism of his vaulting ambition, Alexander is converted to meekness and charity: “At once he put an end to his own desires and ambitions and made room for the exercise of generosity and noble behavior.”

8

The new nobility is quite different from the old pagan nobility.

Beowulf

is both the last gasp of pagan hero culture and an important breath in the rise of the Judeo-Christian humility culture. The truly Christian monster, the one that has completed the arc that

Beowulf

only initiates, will not really be a monster at all, but only a confused soul who needs a hug rather than a sword thrust. True Christianity seeks to embrace the outcast, not fight him. Christianity celebrates the downtrodden, the loser, the misshapen. Grendel is an outcast, and tender hearts have argued that the people who cast him out are the real monsters. According to this charity paradigm, the monster is simply misunderstood rather than evil. Perhaps God has created the monsters in order to teach us to love the ugly, the repulsive, the outcast.

This has become the preferred reading, for example, of Mary Shelley’s

Frankenstein

, and this ethical posture can be seen in some recent adaptations of

Beowulf

as well. For example, Sturla Gunnarsson’s 2005 film

Beowulf and Grendel

gives us a Grendel who is actually just a sad outcast, someone Beowulf even pities at one point. The blame for Grendel’s violence is shifted to the humans, who sinned against him earlier and brought the vengeance upon themselves. Or consider Robert Zemeckis’s 2007 Paramount Pictures version of

Beowulf

, featuring the voices and computergenerated

images of Anthony Hopkins, John Malkovich, Angelina Jolie, Crispin Glover, and Ray Winstone as Beowulf. Zemeckis’s film follows Gunnarsson’s 2005 version in casting Grendel as the sad, misunderstood outcast rather than the evil monster we find in the original. In the film, Grendel is even visually altered after his injury (with CGI effects) to look like an innocent, albeit scaly, little child. In the original

Beowulf

the monsters are outcasts

because

they’re bad, just as Cain, their progenitor, was an outcast because he killed his brother, but in the new liberal

Beowulf

the monsters are bad

because

they’re outcasts. And while the monsters are being humanized in the new versions, the hero is being dehumanized. When Zemeckis’s Beowulf asks Grendel’s mother, “What do you know of me?” she replies, “I know that underneath your glamour, you’re as much a monster as my son Grendel.” The only real monsters, in this now dominant tradition, are pride and prejudice. In the original story Beowulf is a hero. In the 2007 film he’s basically a jerk, whose most sympathetic moment is when he finally realizes that he’s a jerk. It’s hard to imagine a more complete reversal of values.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) wrote, “He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster.” Nonetheless he argues in

Beyond Good and Evil

that the pagan cultures of nobility arose out of barbaric, even beastly sentiments of power, strength, and pride. Unlike Tolkien, who was happy to see such will-to-power tamed by Judeo-Christian virtues, Nietzsche missed the old days and wished we would bring back a little bit of our monstrous selves. He would have liked the pagan Beowulf, a tribal-minded monster killer. Reaching back to a pre-Christian notion of nobility, he quotes Norse mythology approvingly:

In honoring himself, the noble man honors the powerful as well as those who have power over themselves, who know how to speak and be silent, who joyfully exercise severity and harshness over themselves, and have respect for all forms of severity and harshness. “Wotan has put a hard heart in my breast,” reads a line from an old Scandinavian saga; this rightly comes from the soul of a proud Viking. This sort of man is even proud of

not

being made for pity, which is why the hero of the saga adds, by way of warning, “If your heart is not hard when you are young, it will never be hard.” The noble and brave types of people who think this way are the furthest removed from a morality that sees precisely pity, actions for others, and

desinteressement

as emblematic of morality. A faith in yourself, pride in yourself, and a fundamental hostility and irony with respect to “selflessness” belong to a noble morality just as certainly as does a slight disdain and caution towards sympathetic feelings and “warm hearts.”

9

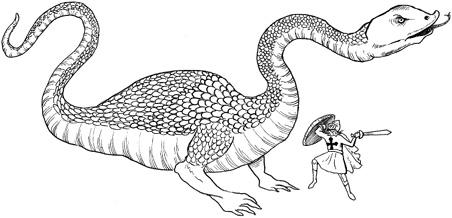

The sign of the Cross, and a little steel, help St. George vanquish a dragon. Pen and ink drawing by Stephen T. Asma © 2008.

Pagan heroes want to be publicly recognized for their acts of heroism; they want honor as payment for their monster-killing services. Beowulf himself says he wants fame. Another medieval hero, the crusader Roland from

La Chanson de Roland

(ca. 1170), is motivated by his desire to have a good song, rather than a bad one, sung about him back home in France. Judaism and Christianity, on the other hand, demote public honor in favor of private honor. According to the Judeo-Christian tradition, prideful men misidentify their proper audience: “They act out the drama of their lives before the audience of their contemporaries rather than before the all-knowing and merciful eyes of God.”

10

This mistake makes them prideful giants, impressive in the short term but ridiculous from the point of view of eternity.

11

Possessing Demons and Witches

Be not angry…for it is not he, but the demon which is in him

.

ST. ANTHONY OF THE DESERT

W

HEN MOST PEOPLE THINK OF MEDIEVAL MONSTERS

, they think of demons, witches, and ghosts—in short, supernatural monsters. This kind of monster is perhaps more frightening than what might be called zoological monsters, deformed creatures and exotic races, because of their ability to possess. The idea that monsters can get inside a human being and use him or her for monstrous ends predates the medieval period, flourishes during it, and continues to the present.

1

The story of St. Anthony of the Desert (ca. 251–356) had a huge impact on the development of Christian monasticism. He is sometimes referred to as the Father of Monks, having created a desert monasticism that drew Christian ascetics far away from the urban centers. But his famous fight with monsters in the Egyptian desert also laid the groundwork for medieval thinking about demons and possession.

2

Anthony was a pious Egyptian boy, born of Christian parents who died when he was around eighteen years old; subsequently, on a religious impulse, Anthony gave away all his property and possessions.

3

He studied with local ascetics, learning how to better discipline his mind and his loins,

and eventually mastered the practical difficulties of living without comforts. “But the devil, who hates and envies what is good, could not endure to see such a resolution in a youth, but endeavored to carry out against him what he had been wont to effect against others.”

4

The devil began by “whispering to him the remembrance of his wealth…love of money, love of glory, the various pleasures of the table and other relaxations of life,” but Anthony remained firm in his regimen of fasting and prayer. So the devil redoubled his efforts to snare Anthony’s desires, even taking on the shape of a woman one night and imitating all her beguiling ways. “But he, his mind filled with Christ and the nobility inspired by Him, and considering the spirituality of the soul, quenched the coal of the other’s deceit.” Anthony then moved to live in a tomb outside the village, where he was attacked by a “multitude of demons” who sliced him into a bloody mess. “He affirmed that the torture had been so excessive that no blows inflicted by man could ever have caused him such torment.” But his faith revitalized him and he rallied back. After throwing off the temptations of the flesh, Anthony was revisited by the devil many times, but the devil always shape-shifted to appear as some creature.

But changes of form for evil are easy for the devil, so in the night they make such a din that the whole of that place seemed to be shaken by an earthquake, and the demons as if breaking the four walls of the dwelling seemed to enter through them, coming in the likeness of beasts and creeping things. And the place was on a sudden filled with the forms of lions, bears, leopards, bulls, serpents, asps, scorpions, and wolves, and each of them was moving according to its nature.

These creatures, together with demonic hounds, attack and torture Anthony, but he insults the devil with audacity, telling him that such shape-shifting attacks are evidence of his weak cowardice. Eventually a ray of light pierces the dark tomb and causes the monsters to disappear. God has intervened, after years of torture. Anthony asks, “Where were you? Why didst thou not appear at the beginning to make my pains cease?” God responds, “Anthony, I was here, but I waited to see thy fight.” Convinced that Anthony has the right mettle, God commits to give him support and strength ever after.

Anthony moves farther into the desert now, finding an abandoned fort “filled with creeping things” and taking up residence there. For twenty years he lives in solitude, fighting temptations and creatures, until other pious young men, hearing of his legendary asceticism, begin to join him in the desert. A reluctant role model, Anthony imparts his wisdom to the new desert monks. First, he explains to the neophytes that one must never be afraid of demons. The devil and his minions may have had significant power

in the old days, but ever since Christ came to earth the evil ones have lost most of their power. After Christ’s victory, Anthony explains, the demons have no power and “are like actors on the stage changing their shape and frightening children with tumultuous apparition and various forms.”