One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution (35 page)

Read One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution Online

Authors: Nancy Stout

She was modifying a role she’d played most of her life, because from an early age she’d brought children—poor children—home with her. According to her sister Flávia, Celia nursed children barely younger than herself, and would give them baths, delouse their hair, dress them in her own clothes, emulating her father. Now, in the Sierra, she was aware of the psychological benefits this outreach would have for the rebel army. Celia had a shrewd diagnostic eye, and what she observed she passed on to those accompanying doctors. All this contributed to the rebel army’s reputation, and soon, when guerrillas showed up, mountain people flocked to their camp because they thought the rebel army could work miracles. It didn’t hurt that priests were there also, the second ingredient in this successful social recipe.

(

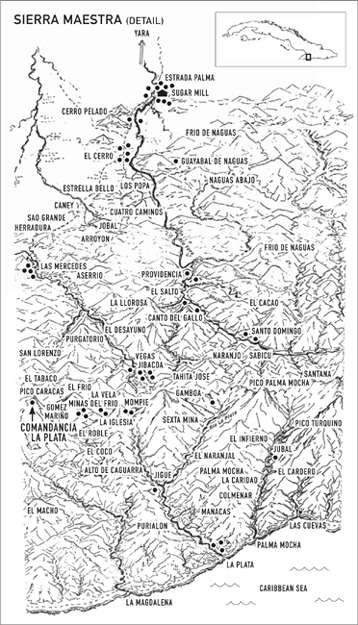

Map drawn by Otto Hernandez. Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos.

)

Father Guillermo Sardiñas joined the guerrillas in late 1957 or early 1958. “Because people knew we had a priest among us, they would ask to be married, or to have their children baptized. And because Celia was present, they’d ask her to be the godmother, and she’d accept,” Rebel Radio’s Ricardo Martínez related, in describing his travels in the mountains with Column 1. (

Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos

)

Three priests, in particular, took turns going into the mountains to be with Fidel’s column: Fathers Chelala and Rivas from Santiago, and Guillermo Sardiñas from the Isle of Pines. Other priests did stints with the guerrillas, encouraged by their parishioners, laypersons active in the 26th of July Movement; but of the three, Father Sardiñas is the most famous. He is described as

celestial

(meaning absent-minded), and sufficiently so to be a handicap because Raúl Castro usually appointed a soldier to keep an eye on this priest. He might just start smelling the flowers—to quote Ricardo Martínez—wander off, get lost, and fall into a ravine. Sardiñas dressed as a guerrilla priest: his soutane was olive green, embroidered with a red star, and had been designed by Camilo Cienfuegos (who had worked in El Arte, a stylish men’s clothing shop located in Havana behind the Capitol, before becoming a guerrilla). Martínez told me: “Because people knew we had a priest among us, they would ask to be married, or to have their children baptized. And because Celia was present, they’d ask her to be the godmother, and she’d accept.” He says that Fidel would step in to take his place as the godfather (and here Martínez sighed, as he related this), causing a certain amount of fanfare every time they camped. Don’t forget, they all looked rather biblical, with their long hair and beards. Plus it didn’t hurt their glory that the “doctor’s daughter” was with them wearing mariposa blossoms, the old Mambisi army symbol of resistance and liberation pinned to her uniform. Nor did it hurt that the rebel army paid for everything in cash.

Lydia Doce, four years older than Celia, managed Che’s camp, El Hombrito, near San Pablo de Yao. In September 1957, Che asked her to be his courier. (

Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos

)

Martínez described how each day ended: they were exhausted and footsore, having been on their feet for nine or ten hours, and wanted only to undress, bathe, and find a place to string up a hammock before dark. Most of all, he says, they were always desperate to know whether the cooks had started a fire, wanted to be reassured of having something to eat before going to sleep. Martínez returned to his theme: they’d be trying to make camp and people from the area would drift in. “They would ask Fidel if he would be godfather, and he would be godfather,” he recalled grouchily, but with fondness. “Other people would need a doctor,” and they could get no rest.

Father Sardiñas officiated at weddings and baptisms and masses all over those hills while he traveled with the rebel army, even though there were no Catholics in the Sierra. The people who came to the rebel camp were spiritualists, primarily, and Seventh-Day Adventists with the occasional channeler. Spanish priests who were sent to Cuba had never bothered to go into these out-of-the-way villages, so there were no Catholics per se. But that didn’t matter, because as soon as someone spotted the guerrillas making camp, word went out, and country people would start to arrive from the surrounding area. Martínez pointed out, “You have to keep in mind that most of us were not communists then. I am confident in saying that we have all become communists along the way. All of us, with the exception of those who were Marxists, had chains with medals of the Virgin Mary. I still have the rosary that Father Sardiñas gave me that I used to wear on my uniform. Fidel had chains with medals. We weren’t the only ones.” Then, he added, after a long moment of silence, as if rousing from a somewhat bizarre memory, “This is a true story.”

WHEN CELIA BEGAN LIVING

with the rebel army in mid-October 1957 she was, in fact, following closely in the footsteps of another woman, Lydia Doce, four years older, who worked for Che. Lydia managed Che’s encampment at El Hombrito after he’d been appointed commander at the end of July, when he’d set off on his own, leaving Fidel’s column to make a permanent camp in another part of the mountain range. It was north of the areas Fidel usually frequented, on the other side of Bayamo. One day, Che went to the small town of San Pablo de Yao to find food, and later wrote: “One of the first houses we saw belonged to a baker’s family.” A month or two later, he asked the baker—Lydia Doce—to organize his second camp, where he’d hidden his men inside a coffee plantation.

In late September, Che sent her to Santiago on her first mission. Che was unacquainted with Frank’s replacement and asked Lydia to make diplomatic contact with the new chief, Daniel (Rene Ramos Latour). Like a pro, she went to a friend’s house first for a complete makeover, changed the color of her hair, and put on a dress. She was plump but had a pretty face; and some photographs of her suggest seductiveness. Getting to Santiago

meant navigating roads controlled by the army. And these she had maneuvered with ease, only running into problems in Santiago. There, the 26th of July rejected her because they couldn’t identify Che’s signature. But Lydia was resourceful; she found an outsider to introduce her to Daniel, and after this episode, Che decided that he wanted her to carry all his messages. She became an executive courier, and within the rebel army this was a high-status position.

She became “radicalized by the experience,” as Cubans frequently comment when speaking of Batista’s coup d’ état. She had been living in Havana but left the capital when Batista took over in 1952. She moved back to Oriente Province in 1955, opened a bakery in San Pablo de Yao, where she encountered Che in 1957. She’d married at sixteen (in 1932) and had three children with her first husband, Orestes Parra (two daughters and a son named Efrain, who joined Che’s column). She divorced her second husband, Sebastian García, after fourteen years of marriage, before moving to Havana in 1952, and had been managing on her own for five years before working for Che.

Che’s camp was stationary (unlike Fidel’s, which was always on the road), and Lydia took care of it. She secured food, medicine, and uniforms for Che’s men—much as Celia had been doing for her outdoor barracks in Manzanillo—was known in the community, and could do this underground logistical work discreetly. She oversaw about forty soldiers in Che’s Column 4 (named Column 4 because Fidel wanted to suggest there were more columns by skipping a few numbers). As Che put it, Lydia “could be tyrannical” and Cuban men found her hard to handle. One of his soldiers complained that she had “more balls than Maceo” because she was excessively reckless, and advised Che to watch out, she’d bring them all down. Che admitted that her audacity had no limitation.

ANOTHER AUDACIOUS FEMALE

was Celia’s oldest sister, Silvia (often spelled Sylvia in the archives). She had been living quietly in Santiago, in spite of Celia’s ever increasing notoriety, with her husband, Pepin Sánchez del Campo, a pharmaceutical salesman, and their two sons. Silvia taught at the Santiago Teachers College. It was a private school, and Frank País had been an intern in her classroom, and he had recruited her. Today, both

of Silvia’s sons remember Frank, his sweet face and his charm, and chortle as they describe the first time they saw him. Silvia had organized a meeting in her house to introduce Frank to a prominent member of the Santiago community, so Frank could ask him to buy weapons, and they were there. Their father, Pepin, came home after work, and Silvia introduced him to Frank. As soon as Pepin got a chance, he pulled his wife into the kitchen to ask her, incredulously, “Are you planning to carry out a revolution with children?” Young Pepin and Sergio then started to discover things around the house: they found armbands in a drawer and surmised that one of the outlawed M-26 sewing circles must be meeting there, too, and decided not to confront their parents—better to keep their eyes open and discover more about what was going on. One day, Sergio, the youngest, came home from school just as Frank’s bodyguard drove up outside their house, got out, and removed a spare tire from the trunk of his car. He knocked on their door and handed Silvia the tire (filled with pistols and ammunition) and told her to get rid of it. Without any pretense, she’d asked her eldest son, Pepin, then eleven years old, to help. She handed him the box of ammunition and told him he’d have to take care of this. She explained the route he’d take, which went right past a policeman, but said: “Don’t let him see it.” The box hadn’t been small; it had been about the size of a large cigar box, or a collegiate dictionary, but he managed.

Soon after Celia went into the mountains, Silvia’s quiet life began to explode. “My father was arrested twice,” and Sergio began to describe his family’s odyssey. Through the spring and summer of 1957, Silvia was pregnant. In November, “my mother was in Santiago’s Los Angeles Clinic and gave birth to a daughter who died at birth.” (Silvia had been RH-negative and the baby was RH-positive, creating antibodies at birth; this was the second child she’d lost at delivery.) The day after she left the hospital, her husband was arrested. “We arrived home from school, my father wasn’t there, and a lot of neighbors were going in and out of the house. We asked our mother what was happening. She answered that our father was in Guantánamo, and that was all she said. Going to Guantánamo was normal, since he was a pharmaceutical salesman,” but when the neighbors left, she explained what had happened.

That morning, the head of the army in Santiago, Col. José Salas Canizares, the man who officially killed Frank País, arrived at their house accompanied by soldiers. They searched all the rooms and found medical samples—no more than normal for a pharmaceutical salesman—and then arrested Pepin and took him to the Moncada. She’d telephoned the mayor, a friend of hers, who was high up in the pro-Batista government. The mayor, Maximilian Torres, and Silvia had been in school together and often chatted at social events. Torres drove to the Moncada and got Pepin released, but Canizares had been tough (according to Sánchez lore) and asked the mayor sarcastically, “What do you think you are doing at Moncada making inquiries about an arrest that is an army affair?” In other words, you might be the mayor of Santiago, but I am head of the entire eastern division of the country. Wasting no time, Canizares informed Mayor Torres that the army had finished their interrogation and were aware that Celia Sánchez had stayed in Pepin’s house at Alta Vista. Furthermore, they knew that Pepin was sending medical supplies to the Sierra Maestra, even though Pepin had denied everything. Still, Canizares said, he would release him. Torres, confused by the about-face, related all this to Silvia, who rejoiced that her husband was free.