One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution (57 page)

Read One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution Online

Authors: Nancy Stout

In many ways, Cohiba is the biggest project of them all. Celia’s business cards in the 1960s were engraved on very thin pieces of cedar, the kind used to separate the rows of cigars in a box of export habanos. And she encouraged a line of clothing (produced in a fashion workshop named Verano, which also produced sugar-sack dresses worn with “Cuba” belt buckles) made of the gauzy fabric used in the fields to cover high-grade wrapper tobacco.

CELIA LOVED ARTISTS

. And at the beginning of 1968, Danish abstract artist Asger Jorn painted murals in her office at the Archives. Jorn had come to Cuba to participate in an exhibition at the invitation of Wilfredo Lam, whom he’d met in Paris in 1946 when they were young unknown artists and Jorn worked for Fernand Leger and Le Corbusier. Their friendship deepened in Italy, where they shared a ceramics studio in Abisola.

After the exhibition was over, Jorn wanted to stay on and do something more for revolutionary Cuba, and just how sincerely he meant this can be illustrated by the fact that just a few years earlier, in 1964, Jorn was given a prestigious Guggenheim award for $2,500 but refused it. Only recently has his telegram to Harry F. Guggenheim become public. It read: “Go to hell bastard. Refuse prize. Never asked for it. Against all decency mix artist against his will in your publicity. I want public confirmation not to have participated in your ridiculous game.”

Jorn contacted Celia at the suggestion of Carlos Franqui, who was in Paris. He found a sympathetic home at the Office of Historical Affairs; it seems likely that he painted Celia’s office first,

then moved on to the walls in the large room on the ground floor (formerly it was a bank), hallway, stairwell, and mezzanine. Late one night Celia jokingly painted a little mural of her own. Using cans of paints he’d left on the floor, she drew a scene from the Sierra Maestra, with a tank and some palm trees, expecting him to paint over it. But he didn’t.

IN THE FIRST EIGHT YEARS

of the Revolution, Celia authored at least three truly great projects: Coppelia, Cohiba, and the archives. In the last of these, she was betrayed by one of her carefully selected staff members, a man she’d appointed director, who copied the archive’s contents and left the country in the late 1960s. Carlos Franqui—almost always referred to by her family and colleagues as “a traitor to Celia”—went abroad on a project at Celia’s behest and took, without her knowledge, photographs he’d made of documents she was preparing to publish in a book. This was to have been the archives’ first publication of primary correspondence and other documents from the war. What exactly Carlos Franqui did remains subject to debate, but one thing is clear—he was not a “whistle blower,” stealing material and divulging it to set a record straight. He simply wanted to scoop the archives, and get the glory for bringing these materials to public view.

Franqui had been in the Havana underground, and was sent during the war to the Sierra Maestra for safety. He was the editor of the newspaper

Revolución

, the organ of the 26th of July Movement, published in the first months of 1959, after they’d gained power. He was dismissed, but not for anything personal. In a media revamp, he emerged with a less favorable position, and complained about it. I did not interview Franqui before his death, but I know that Fidel rarely entertained objections—unless you’d been there at the beginning with him, at Moncada or on the

Granma

. Celia had given Franqui a job in the new office she’d set up, where they were seriously cataloguing the Sierra Maestra material. The office was located in a bank one block from Once. Franqui worked there, for her, before he went abroad. She was so confident of his return, although he kept extending his stay, that for two years she made sure he received a salary from her office, and sent money for his child’s operation. He began publishing the material in Mexico, Spain, and in the United States. Since she’d been preparing this material for publication herself, she naturally took this personally. From what I was told, she reacted in a quiet, refusal-to-discuss, heartbroken manner.

Cuban artist Wilfredo Lam, left, and Chilean painter Roberto Matta, center, raise their glasses in a toast with Celia and others, at a 1967 reception held in the Palace of the Revolution. (

Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos

)

I came upon the Franqui conundrum inadvertently, through asking one innocent question: “People are shaped by their successes, but even more so by their losses. What were Celia’s greatest disappointments?” It was one question from a very small set that I asked every person I interviewed. Better than 90 percent of the answers had been just a name: Carlos Franqui. Writer Miguel Barnet simply comments, “Franqui is a fake. He re-created material.” Later, after I’d been given access to the archives, and to original documents, I began to see what Barnet meant by this somewhat enigmatic statement. A Franqui text I’d stored in my laptop differed significantly from the text in the original document. Mostly, it was conceptual content that was altered. One obvious example is

Doce

, Franqui’s early book about the “twelve” survivors of the

Granma

when he, better than anybody else, knew there had been sixteen (immediate survivors; or twenty-one, depending on how you count them). But Franqui evidently preferred a biblical metaphor; no doubt it sold better.

Julia Sweig, Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, in Washington, researched documents in the archives in the

Oficina de Asuntos Historicos

, Office of Historical Affairs, in preparation for her doctoral dissertation. She hits the nail on the head regarding Franqui: “Because of my extensive access to the OAH collections, I had the opportunity to compare many of the original documents with the version published in the 1976 and 1980 collections and with those housed in Princeton University Library’s Carlos Franqui Collection, which contains the photostatic copies of the material that Franqui photographed. I found in many cases that the published documents omit substantively significant portions of the text in the original documents, but without the standard use of ellipses to indicate where text has been left out. In other cases, the published version of the document is misdated.”

I knew Franqui’s material well before I was permitted to use the archives, and have had the luxury of making my own comparisons. Other historians have not always had that privilege, since the archives have not been readily open to scholars—and likely will remain, as is the case with most archives, closed to the general public.

Franqui’s books leave most of us, desperate as we are to figure out what went on among those crazy revolutionaries, in a state of confusion. I pointed out to Barnet that Franqui is usually quoted as saying he left Cuba because the Castro government had turned Communist. “I met Franqui in Europe. He was there two years before he defected. He was the pro-Soviet one,” Barnet said, and laughed. “Later, he told everyone the opposite.”

When I was finally given permission to use these documents, one of the first questions I asked the director of the OHA, Pedro Álvarez Tabío, was about the material Franqui had been publishing for decades. He explained that the documents were never in jeopardy, but their publication is considered a theft—which, under international copyright standards, it undoubtedly was. Tabío also showed me a carbon copy of Celia’s book, never published.

While plenty of other people defected, or at least left the country, Franqui falls into a special category: the corrosiveness of the books he produced, filled with discrepancies in narratives, usually failed to explain their shared history, and Cuba’s, fully. Most Cubans I questioned see Franqui as a manipulator of friends,

and of facts. The latter is unforgivable since it concerns their own history. “He’s not a good writer. He isn’t even a good journalist. He is an opportunist,” Barnet summed up Franqui’s faults. Then he added softly, “He was a friend of Celia’s.”

Photographer Lee Lockwood, whom I consider a reliable source, told me that sometime in the early 1970s (so not quite a decade after Franqui left the country), when he was in Cuba photographing Fidel, they were in a house outside Havana, and Franqui was there, at the same location, visiting Celia. Who knows what was said at that meeting. Was it reconciliation?

The problem lay very close to her heart, Celia’s nephew, Silvia’s son Sergio, suggested. “Every night Carlos Franqui came to Once, jacket thrown over his shoulders, when he was the director of the OHA. He had the combination to the vault. He took the Sierra documents.”

“Copies of them,” I corrected. But then I wondered, do I really know that?

39. T

HE

1970s

The Kids, Lenin Park

IN THE ELEVENTH YEAR

of the Revolution, Fidel decreed that the country would bring in its greatest sugarcane harvest ever: the goal was 10 million tons. “Fidel would cut a lot of cane,” Tony laughed, recalling those days at Once. “He would get home at whatever hour, all full of red soil, and his boots covered in mud. We didn’t have an elevator then. He’d go up the stairs, and Roberto would boil. He’d just cleaned the stairs. Now he had Fidel’s boots to clean—and he would make them beautiful. And Fidel would put the boots on and leave, and five or six hours later, it would happen all over again. Roberto would roll his eyes and blow through his teeth. This would happen day after day, over and over. It wasn’t only Fidel. It was all his personal guards who walked upstairs with him.”

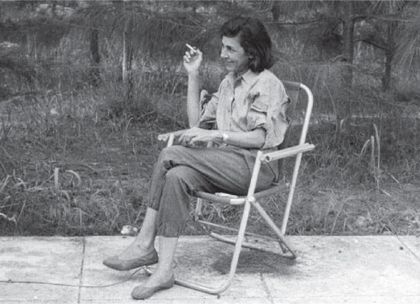

Everybody cut cane. Celia cut cane. She wore her old Sierra Maestra tunic with its wide belt, heavy gloves, and wielded a machete. There are many photographs of her in the cane fields, and not one with a smile on her face. The country cut 8.5 million tons, indeed the largest harvest in Cuban history.

THE SAME YEAR

, construction began on Lenin Park, and Celia was in charge of this exceptional project. Its purpose was quite explicit: to protect a huge tract of land that sits above the city’s aquifer. There are three parks that protect the aquifer, and this

section would make that protection complete. They needed to expropriate the land and get rid of a highly toxic textile factory discharging dyes directly into a stream. First, Celia shut down the factory and had it removed. Lenin Park was a huge undertaking, and the costs were spread through different ministries. She got it off the ground by using her power as a member of the Central Committee. Completing it required volunteer work from many different institutes and schools. Every member of Celia’s extensive family can tell you about doing volunteer work there.

IN 1970, CELIA TURNED FIFTY

, and did so with a house full of teenagers to contend with. Besides the basic four (Eugenia, Teresa, Fidelito, Tony), there were three brothers named Luis, Ezekiel, and Jesus, who were scholarship students in the Cojimar house. Fidel had invited a fourth boy, Ramon Fuentes, whom the kids called Escambray, to join this group.

“What happened to Escambray was similar to my brother and me,” Teresa explained. “During one of Fidel’s visits to that area, he met a family and they talked. Fidel liked the boy a lot, and wanted to know what he wanted to be when he grew up. Escambray told Fidel that he wanted to work in aviation. Fidel talked to the family, as he’d talked to my family.” He was one of thousands of farm children who came to the city to study. Few returned to the countryside, even though the government was building universities everywhere outside Havana, with the assumption that children would further their education in their own provinces and become leaders.

“When Ezekiel had a fever,” says Teresa, “he came to Once to be cared for.” Ezekiel was the youngest of all the children, and Celia kept her eye on him. “He stayed there, from then on. Luis, Ez, Jesus, and Escambray would spend the weekend in the house. Or go on Saturday or Sunday. It reached a point that Celia said, don’t go back there, stay here. This is when she built an extension on the Once house.” There were extra bedrooms with bunk beds. The three brothers appealed to Celia to let their sister come to Havana. Ondina Menendez Sánchez joined them (and still lives at Once), with lots of medical problems. She’d come to the right place: she had an operation on her legs after she arrived, one of many, and she was fifteen. In addition there was a boy named Arcimedes from Ecuador who stayed there briefly, joined by his two brothers. Today Jesus and Fidelito are dead; Escambray is a career officer in the military. When I thought I was going to meet him, he had to get permission to give an interview to a foreigner, which wasn’t granted. And I never managed to speak with Ezekiel. Teresa would set the interview up, and he’d equivocate.