One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution (54 page)

Read One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution Online

Authors: Nancy Stout

I see it as an unbreakable friendship. They may have been taking a stab at being utopian, but I doubt it. Their highly private, dovetailed alliance started in the Sierra Maestra. Why would these two, of all people, think they had to account to anyone for their private lives? They were revolutionaries creating a new society, and as guerillas had been more than ready to lie about whatever must be protected. In the 1960s, what had to be protected, above all, was the Revolution, and that, it seems to me, is the tie that binds.

36. 1964

The Archives

IN 1964, CELIA ESTABLISHED

the Office of Historical Affairs, officially founding the archive on May 4, simply by announcing it in a conversation with a group of people at her house. I don’t know who these people were, but she informed them that she had decided to create an office that would function as an institution responsible for the documents. It would operate under the direction of the secretary of the presidency (herself). “In this manner, characteristically informal, and from her living room,” historian Pedro Tabío Álvárez writes, “the

Oficina de Asuntos Historicos

was born.”

Some of the material is transcribed, some are facsimiles; all the original materials were copied on microfilm and onto 35mm film, starting in 1964, by Raúl Corrales; the documents are organized by author and date: “It was the custom of Fidel and other guerrilla chiefs to note the date and hour of their writing,” Tabío noted. Next, Celia hired a small staff (friends from the underground, like Elsa Castro) to visit soldiers, make interviews and record them, and she built up a photo collection.

The entire project was eventually adopted by the Council of State. This is the highest governmental body in Cuba, generally numbering 10 to 15 members. Not all those on the Council of State are politicians—some are scientists, farmers, writers. Today, her great trove of primary source materials serves as the country’s official archive of the Revolution, and as its presidential library. Unofficially, it’s called

Fondo de Celia

, Celia’s Archives.

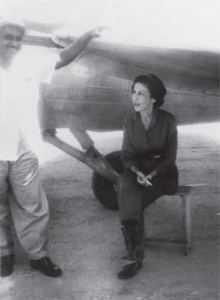

Celia never forgot the 26th of July Movement’s debt to the people of the Sierra Maestra. Here she is in late 1963, waiting to board a plane to make one of her many trips to Santiago de Cuba. (

Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos

)

She was not a diarist, although she longed to record her days in the Sierra, and bought a diary for that purpose. According to Nydia Sarrabia, Celia started a diary on March 1, 1958, but other than the date, left the opening page empty; then, on March 6 she wrote, “Never did I think I’d write a diary. My life never seemed interesting enough to write trifles. The war and these circumstances oblige me to note things of interest to make sure that the history of Cuba is true. Raúl has recorded all the facts since the beginning of the Revolution.” But in the end, she filled only the first few pages.

In the mountains, however, she began to make copies of Fidel’s letters and started keeping her own notes; she began to develop the collection, starting with herself and Fidel first, then, within a month or two, requested materials from the other commanders. Some records, at her suggestion, were buried in mason jars, and these, according to the curator of Celia’s documents, Nelsy Babiel, still turn up under farmers’ plows in the Sierra Maestra spring.

37.

The Florida Story

CONSEQUENCES OF THE REVOLUTION

persist in nearly every Cuban family. When the prisoners taken at the Bay of Pigs finally left Cuba in late December 1962, Celia’s sister Chela and her husband, Pedro Álvarez, were on the same boat, emigrating to Florida. As with all Cuban families, their story is seen across the 90-mile divide.

The Álvarez family had returned to Cuba in 1959 to participate in the Revolution, and that is when the boys went to the Jesuit-run Belén school and stayed in Celia’s apartment. The Álvarez family hoped—at least for a time—they could live within the Revolution. Celia must have hoped that Pedro could help the 26th of July Movement government by heading up the Rice Institute. But as seen from the Cuban side of the divide, the Álvarez family was not “mentally prepared” for what was taking place, and left. And in this, Celia’s extended family mirrors nearly every Cuban family at that time, many of which are divided into two parts: those who stayed, and those who decided to go. The typical Cuban family may not have such dramatic characters, nor assassination as a plot, but it would be hard to find a family with 100 percent of its members remaining in Cuba.

Celia’s sister Flávia, from her penthouse overlooking the Malecón, told me the following in 1999: “Pedro Álvarez was a

millionaire, the owner of a rice mill in Manzanillo. . . . And when the Revolution triumphed, Fidel proposed to make him the head of the Rice Institute of Cuba. But he didn’t accept because they were already talking about Communists, and it was like a four-letter word. He was afraid, but kept working until his business was nationalized.”

“We lived in the Focsa Building, in Havana, in a large apartment on the twenty-third floor,” Chela explained from her nice though modest house in suburban Miami, and “were asked if we wanted to trade the apartment in exchange for coming here. We came. We didn’t have to pay. Three of our children, our sons, were already here. As soon as they closed the Colegio de Belén, our sons came. Our daughter stayed in Havana with us.”

“All of the family, including Celia, advised Chela to go,” Flávia confirmed. “Her children had left. Only her husband and one child remained. The boys had left Cuba. It was not a time like now, when they could come and go. Then, it was a matter of forever. . . . They wanted to leave because the priests had advised them. . . . You know the position of the Church in those days.” The boys had been in an evacuation of children to Miami, now known as Operation Peter Pan, which took place between 1960 and 1962. A Roman Catholic priest in Miami, aided by the U.S. waiver of visas for children under sixteen and fueled by CIA-planted rumors that all Cuban children would be sent to the Soviet Union for their education, flew 14,000 Cuban children to Florida. Although their children had gone ahead of them to Miami, Flávia assured me, “It was very hard for Chela and Pedro to leave the country and go to live there.”

A realist, Celia never held out much hope for Pedro as a revolutionary. Flávia says that Celia simply said to Chela, “You can stay here, but your children are there, and you will be separated. So you had better go to be with them.” Flávia continued: “They went in the boat that came to pick up the Giron [Bay of Pigs] prisoners. Celia arranged to have them taken with the mercenaries. When they arrived in Miami, their son was already in a training camp of the CIA.”

“WE WENT ON THE PLAYA GIRON

exchange ship,” Pedro Álvarez, in Miami, said, confirming what had been reported by his sister-in-law.

“When I took the luggage, when I got onto the ship, I said nothing will harm us again. Then, one of my sons was a patriot, in favor of the [counter-] revolution.”

WHEN THEY ARRIVED IN MIAMI

, Flávia continued, “Pedro and Chela went in search of him because they were shocked at what he’d done. They arranged to take him out of that camp.” The young man’s name was Guillermo (he was also referred to as William) and joined a paramilitary group when he was eighteen years old. He’d been recruited and trained by a Florida-based terrorist group that carried out missions in Cuba.

IN MIAMI, PEDRO SPOKE ABOUT

the group, confirmed that it was sponsored by the CIA, and said his son had been attracted to them. “They had infiltrated before. They had been on these missions. They’d done this stuff before. The people who infiltrated Cuba openly talked about it.” Pedro and Chela brought Guillermo home and thought that that would be the end of it.

“AFTER THAT, HE STARTED

to work in a parking lot,” Flávia said, to fill in some of the story. “The only one in the family who wrote to him was me. There was no regular mail between the two countries, so if I knew someone was going to Mexico, I’d send him letters. Celia knew. When I got Chela’s mail, Celia would ask, ‘What did she say?’ and I would go over to Once and show Celia the letter. Fidel appreciated their attitude. He appreciated that they didn’t make any statement to the press when they arrived.” Another member of the family commented dryly, “Fidel behaved elegantly because Pedro left four million dollars in the bank.”

The family thought that Guillermo had broken ties with the CIA, but one day, in May 1966, he casually mentioned that he was going fishing and, instead, went on a mission to Cuba, where he was killed. The operation’s lone survivor, named Tony Cuesta, identified the others, including Celia’s nephew.

GUILLERMO’S PARENTS

are understandably filled with anguish, although four decades have passed since his death. Chela lamented sadly, “People said: ‘Don’t take these young boys.’ But Tony Cuesta went to a party and told them: ‘We have a mission.’ And Guillermo

went.” Pedro was fatalistic: “If they hadn’t killed him that day, he would have gone back [to Cuba]. . . . He was very tough, since the day he was born. He wasn’t afraid of anything or anybody.”

In Havana, I spoke to his uncle, Comandante Delio Gómez Ochoa, who confirmed all the parts of the story. “I knew the boy William—Guillermo. I knew all the children. In 1961, when I came back to Cuba, I met them.” (Ochoa led a column in the Sierra Maestra, became Fidel’s liaison in Havana during the last months of the war. In 1960, he went on a mission to overthrow General Trujillo in the Dominican Republic. When he returned, he married, and eventually divorced, Celia’s youngest sister, Acacia.)

Ochoa is retired from the army now, and we spoke at his house in Playa, which is not far from the sea. “The landing was close by. It was an operation set up by the CIA in order to attack the president’s house; the president was Dorticos. He lived near the Chateau Miramar. . . . There was a large area between 5th Avenue and the beach, where the Hotel Havana has been constructed, on the other side of 5th Avenue. All of that area was known then as El Monte Bareto. It wasn’t a mountain. There were a lot of trees and a lot of growth that extended from the other side of 5th Avenue all the way to the coast.

“They came in a very fast boat. We didn’t have boats with that speed. They landed. Those who remained on the boat were discovered by the Cuban coast guard. A militia unit nearby were the ones that encountered them.”

The small fast boat from Miami landed on the beach with enough time to set up missiles before the Cuban militia attacked them. Some members of the party went into the Monte Bareto woods, but Guillermo got back into the boat. By that time, Cuban units—Ochoa said these were small boats with radios—closed in, and they exchanged fire; then two other units of the Cuban coast guard intercepted the boat in which Guillermo was alone, at the wheel. When the coast guard arrived, they ordered the boat to halt, but it didn’t. “So the coast guard started shooting, and one of the shots hit the gasoline tank of the boat, and it exploded. That is how the action ended.”

“He was blown to pieces,” is Flávia’s version. “Pedrito, his father, called his cousin to . . . request [that] the government give them the remains.” There were none. Flávia says that Celia could

do nothing, although she tried. “She told the cousin to go to the general staff of the navy, to be officially informed. They told her that they had not been able to find anything at all because the boat had carried a huge amount of explosives.”

Tony Cuesta, hit by a grenade, survived. Ochoa recalls, “He lost one arm and one eye, and was in prison for a long time here in Cuba, [and] when he was captured, talked about it. . . . For about four or five days they looked for the remains of the boat, and they could find nothing, and felt that the Gulf Stream took it out. They even sent divers to look for it. They traced the exact spot and sent divers down, but didn’t find anything. The navy divers searched for days.”

Another relative, who had work in the Ministry of Foreign Relations, told me that it is generally assumed that Guillermo had been recruited because he knew Celia’s apartment on Calle Once. He’d also come to Cuba to participate in one of the CIA’s attempts to kill Fidel.

Guillermo’s older brother, Jorge Álvarez, lives in Miami and supplied an important detail no one else mentioned: “I spent two weeks with Celia in Havana when I was twelve. My father sent me to Havana with her, asked her to get me into the boarding school Belén. While I was in boarding school, Guillermo and I spent a lot of weekends with her. We slept there once a week for a period of six or eight months.” When he went to Miami, Guillermo would have been fourteen. It would be unusual for a fourteen-year-old not to mention that Fidel Castro lived in his aunt’s apartment, and even stranger for a CIA agent to ignore this information.

The family was shocked by Guillermo’s death. For a time, no one spoke about it. Still grieving, Pedro Álvarez said to me in 2000, “And there is another thing: when they killed our son, we knew that all of them [in Cuba] were crying, but no one bothered to send us a cablegram. They were afraid of what would happen to them there. No one sent an expression of grief. This child was one of Celia’s favorites. She didn’t even call.”