One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution (40 page)

Read One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution Online

Authors: Nancy Stout

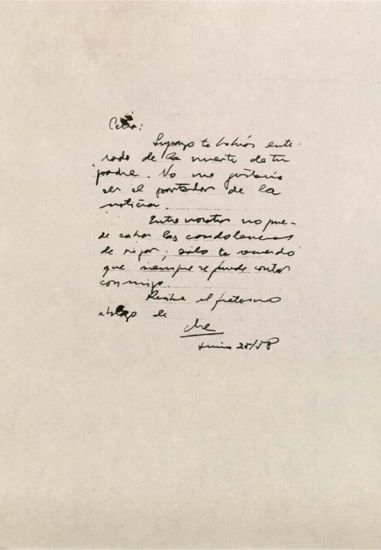

On June 24, Celia’s father died in Havana. A news bulletin was read hourly over Radio Reloj. Che heard the braodcast and wrote: “Celia: I suppose you’ve learned of your father’s death. I wouldn’t like to be the bearer of this news. Between us there is no space for formal condolences; I only remind you that you can always count on me. A brotherly hug from, Che.”

Gossip played heavily in the army’s attempt to catch Celia, and they bought the news on the street that Celia Sánchez was going to make an appearance in Havana. Unable to capture her at the hospital, the army thought their final chance lay in her appearance at her father’s funeral. They cordoned off the street around the funeral parlor. In Cuba, funerals take place within a short period following death—usually no more than a single, day-long viewing period, since bodies are buried without the usual elaborate embalming process. Mourners’ identities were checked at the door of the funeral parlor, which offended many of the distinguished poets, politicians, artists, and physicians who numbered among Manuel’s friends and consequently resulted in complaints to the army. A Manzanillo senator telephoned Batista, and the identity checks were lifted, but the army posted men holding rifles around the parapet of the building, which was located right in the heart of Vedado.

The funeral parlor was on La Rampa, at the time a stylish street with airline offices, which runs like a ramp from the sea up to M and Calle 23. The funeral parlor was next to the entrance to the Polynesian Room on the Rampa side of the Havana Hilton. When the service was about to begin, every seat was taken. Since the 26th of July Movement had sent a huge wreath, with its name prominently displayed on the ribbon, people assumed that all these unrecognizable guests were members of the underground. Flávia told me that she and Acacia, both blondes, had dyed their hair black and dressed “uncharacteristically” in blouses with big flowers to look like country women from Oriente Province; and that she and her husband, Rene, sat apart. Silvia and Pepin came (neither family allowed their children to attend). No one in the family could identify most of the people in the room. Mariano Bofill arrived. Bofill was the owner of the largest foundry in Manzanillo, which manufactured parts for sugar mills. Griselda was briefly married to his son, and they had a child, Julio César; Bofill still kept ties with the Sánchez family and his grandson. He came in minutes before the service began, looked around for acquaintances from Manzanillo to sit with, and saw no one until his eye fell on Silvia and Pepin. He whispered in Pepin’s ear: “It’s too crowded.” Then, suddenly able to recognize the crowd, he’d growled in a low voice, “This is disrespectful. Come with me.” In the hall, Pepin

confirmed that none of the guests were from Santiago, and Bofill, who was close to Batista, dialed the president’s number. Bofill’s early fortune, from the 1920s, was based on scrap metal, and one of his suppliers had been the young Fulgencio Batista. According to Silvia’s son, Sergio, when Batista wanted to enter the army, Bofill had furnished a recommendation. The two men had close social ties and most people assumed that Bofill was a

batistiano

, but both he and his sons made substantial contributions to the guerrillas in the Sierra as well.

Bofill stood at the bank of telephones in the lobby of the funeral parlor, with Pepin next to him, and his conversation has been passed down to the next generation, as if scripted: “I’d like to speak with Fulgencia, this is Bofill calling,” It was not lost on Pepin that Bofill had Batista’s personal telephone number. “Fulgencio, I’m at the service for Celia Sánchez’s father. You know I have ties with this family. This place is full of people from the SIM, and I feel that it is disrespectful to the family. I’d be very grateful if you’d take care of it.” And, according to the story, Bofill put down the phone without waiting for Batista’s comment. Minutes later Tabernilla, the obese, much-hated and greatly feared officer who ruled over Havana, waddled in, clapped his hands twice, and the unknown guests left. Soon only a few people were left in the room to attend Manuel’s funeral.

Flávia gave me a general outline of what happened. I’d known about the police on the parapet, confirmed Flávia’s description with that of the Gironas, and tried to find someone who could recall being at the service on the day of the funeral. Sergio was under the impression that Delio Gómez Ochoa had been there. He was Fidel’s man in Havana, and married Acacia after victory. When I asked him, Ochoa looked at me in astonishment. He answered that of course he wasn’t there; it would have been “suicidal” to have put in an appearance.

This part of Celia’s life story, so far removed from where she actually was at that moment—in Mompié—unfolded with textbook precision. Here was the nation’s army throwing its resources into capturing a woman who was unlikely to make an appearance—an army caught in a trap, trying to keep up its reputation. Having let Celia slip through their hands once, at Campechuela, the army was plagued by its mistake and was always trying to make sure

it wouldn’t happen again. The generals, it seems, couldn’t take a chance that she wouldn’t come to Havana, so they ended up doing what traditional armies often do: spend a huge amount of time, energy, and money on something that is unlikely to happen. Guerrilla armies are effective if only because they allow the establishment to overextend itself, in just this kind of effort. Here was proof of it.

Just as the Cuban military was caught up in an age-old Bismarckian set of behaviors, futile and predictable, so, too, in its own way, was the Sánchez family. After the secret police left, there were very few people in attendance, and one of the unrecognized guests introduced herself to Manuel’s children. She had, for a decade or so, been Manuel’s lover. One of the grandchildren thinks the affair began in Pilón in the 1940s, and that the woman moved to Havana, where Manuel spent most annual vacations. Manuel’s other children had no idea of her existence, and were shocked when she approached them. But the Gironas say that Celia always knew about the affair. For all her apparent closeness to her siblings, she chose not to inform them.

None of the members of the family who attended the funeral are alive today. I cannot ask Flávia for details, because she died (of cancer) in 2004. Griselda’s son, Julio César, who was the first person to tell me about his grandfather’s lover, is also dead. Sadly, so are the Gironas, who were a worldly lot, and of the opinion that Manuel, widowed at the age of forty, would have been happier had he married. Instead, Dr. Sánchez had a long affair with a woman he couldn’t marry, because he never ceased touting his wife as “the love of my life.” Where these fabrications left off, the Manduley women took over. The Gironas told me that no extra women were allowed in that family after Manuel’s mother-in-law and sister-in-law moved into his household. I would discover that anger erupted that day along with anguish over Manuel’s death, and not just over the SIM and the girlfriend.

Chela, Manuel’s second daughter, wasn’t at the funeral because her husband, Pedro Álvarez, had taken his family to Spain, allegedly on vacation, but in truth he’d gone away to avoid the funeral. Pedro himself told me that his wife had been too nervous to attend. He’d been worried about her to the extent that he’d taken her away from Havana, for her health. Pedro cited

the genesis of Chela’s fears: she was arrested on Galiano while shopping for jewelry because the police thought she was Celia. The police had released her almost immediately. Yet Pedro—forty-two years later—was still wrapped up in concern for his wife’s anxiety symptoms, describing her occasional blackouts after she was arrested and said he’d taken her out of Havana on doctor’s orders. Pedro still didn’t understand, when we spoke in Miami in 2000, how much this had annoyed the others. In his mind, he’d solved any further confrontation between his wife and the police by taking her away. To me, it makes some sense, since the police had been anticipating Celia’s appearance in Havana all through April, May, and June following her father’s diagnosis.

Retired comandante Delio Gómez Ochoa, who became Pedro’s brother-in-law after he married Acacia, considers the decision Pedro made to have been cowardly—although he didn’t use that word. He said that Pedro’s behavior was “not good enough”—even in this unusual situation.

Ochoa himself is something of a hero. In the first year, after victory, he led an expeditionary force against the Dominican Republic’s dictator, Trujillo. The first time I interviewed him, it was on the wide verandah of the Writers Union on 17th in the Vedado section of Havana. Filmmaker Lisette Vila, the union’s director, arranged for us to be at the front table, nearest the elaborate iron gate that marks the entrance. People appeared out of nowhere wanting to shake his hand: union members and people even came in from the street; they thought nothing of interrupting my questions to say hello to this old warrior. For the second interview, we sat in his sunny dining room in Playa, and were interrupted only once, by a messenger from Juan Almeida bearing a Christmas card.

Ochoa reminded me that Manuel Sánchez Silveira had been an exceptional man, and an outstanding father. Speaking of history first, Ochoa pointed out that Manuel had had every chance to leave Manzanillo when he graduated from university: he could have spent his life in Havana. And, because he was so charming, Manuel would have become a rich, successful, urban physician. But Manuel had chosen instead to be a public health doctor. Dr. Sánchez had worked among Cuba’s most impoverished people, in one of the country’s most out-of-the-way places, and had spent a

lifetime battling conditions that were the result of bad governments: malnutrition, addiction, and complete absence of social justice. He’d confronted these evils bravely, and had taught his children to face these circumstances head on. Since those elements are the mother of all revolutionaries (paraphrasing José Martí), Ochoa continued, winding up his explanation, by saying that he couldn’t understand how one of Manuel’s children could not choose to be near him at his death. No one who understood or admired Dr. Sánchez would have taken a vacation when they knew Manuel’s death was imminent—or that is how Ochoa felt about it.

From Pedro’s point of view, it hadn’t been quite that easy. He had worked out a kind of compromise: he’d made an agreement with his wife before leaving Cuba that they’d fly home for the funeral if her father died. Various grandchildren filled in the rest. When the telegram arrived, Pedro didn’t give it to Chela, and she did not find out that her father was dead until they returned to Havana. Angry, she threatened to divorce Pedro. Sergio Sánchez says, “She became so intent upon divorcing him that the family intervened.” Pedro must have reasoned that if the police are so sure Celia will come to Havana, who am I to say otherwise? He probably envisioned her popping up in his apartment in the Focsa building, then the flashiest building in town. Chela, for her part, must have buried her head in the sand because she could have made telephone calls, if not to her sisters in hiding, then to the Girona family, or she could have phoned Calixto García Hospital from wherever she was vacationing in Spain. Chela simply did not, because her husband was in charge of everything. When I interviewed them in Miami in 2000, I would turn my head directly to face Chela and explicitly ask her questions, but Pedro would answer them.

FROM JUNE 27 TO JULY 10

, the rebel army held their ground against the Cuban army—but barely. Gradually, things began to change for the guerrillas; they were getting better, although they seemed to be worse. Attacks now came from two directions. Under the command of Major José Quevedo, the Cuban army now had a company of men directly below La Plata, and were going up the mountain toward Fidel’s headquarters. Numerous companies were closing in on the rebels on Che’s side of the mountain, coming

from the north and east. As Quevedo and his men ascended the mountain, Fidel realized that here, at last, was a chance to pick them off, one by one. He sent for Celia on July 8 and they rendezvoused at the rebel army’s military academy in Minas del Frio. She stayed with him during the following month as he directed battles, she in a role akin to that of handmaiden to Mars. On July 10, they had reached the slopes above Quevedo’s soldiers, who’d established an enemy position at El Jigue; here, Fidel decided to establish a command post to battle Quevedo. Celia set up his headquarters on the 11th: she found the site, made sure Fidel had a table and chair, a lamp, a first-aid station, food, a safe water supply, cigars, extra pairs of glasses, etc., and was around to greet soldiers when they arrived, give them Fidel’s orders, and field their questions. That way, Fidel was free to think, to make plans for the hours ahead. It worked well, mostly because she was so adept at keeping people out of his hair. Commanders have told me that they got into the habit of speaking to her first.

Two days later, on the 13th, she sent a message to Che: “I only had some change . . . and a one-thousand-peso note that someone took to change, and it won’t arrive [back] until Tuesday. Everything is quiet here.” The tables have turned: it is Celia who sends notes by messenger to Che, and he is the one with the telephone. “Tell Camilo to send us 20 pairs of shoes from the ones Medina purchased. He is the only one there who can give them out and do so exclusively to the troops and the messenger.” Che will call the

Comandancia

La Plata, which is being defended, in Fidel’s absence, by Camilo Cienfuegos, and discuss the shoes they’ll need for the upcoming battle.