One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir (35 page)

Read One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir Online

Authors: Suzy Becker

“I’m not going to make these for anybody else, not with the three kinds of metal.” There were tears in her eyes when we thanked her. “I’m sorry, I feel stupid. We’re celebrating your birthdays.”

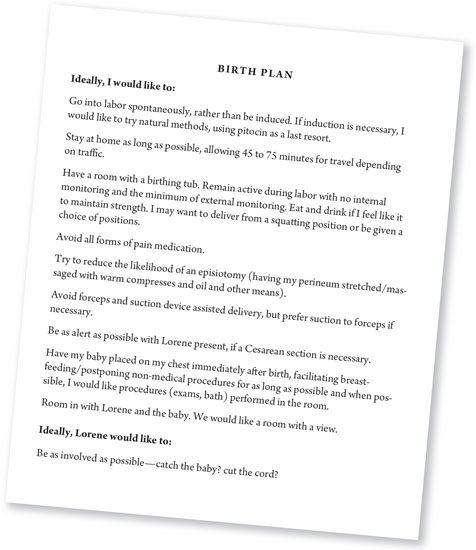

“That’s fine, I’m trying to forget mine,” said Lorene. Her friends, plenty of whom were grandmothers, didn’t hesitate to tell her she was nuts for having a baby at fifty-three.

“I’m worried I’m going to feel left out. The only one without children. You and Meredith will bond even more, the kids will play together . . . ” She wiped at her eyes. “I really miss Meredith. We used to talk every night when we were making dinner, but at least I felt like I still had you two.”

It made me sad she didn’t have someone of her own. “You’ll still have us. It’s not like Meredith and Jonathan; we work for ourselves. We may not be able to get out this way as much, but you can always come see us. And Mommy still calls her guest room your room,” I joked.

“See? Stop it. The two of you will have your kids and I’ll be taking care of Mother.”

Our last morning in Vermont, I was squatting in front of the refrigerator naked, surveying the remains of our weekend provisions, and I sneezed. “These pelvic floor exercises aren’t working,” I yelled to Lorene. I had switched my weekly exercise outing from prenatal exercise to prenatal yoga at the end of the session, but I had kept up the daily “workout” at home.

“You should be doing Kegel exercises all the time—do them when you’re standing in line at the supermarket.” Lorene had the camera.

“Oh, no. No, no, no.”

“What? Your baby is going to want to see pictures of your belly.”

I never saw pictures of my mother’s belly. “My baby is

not

going to want to see pictures of her mother naked.”

“She won’t mind seeing you naked until she knows you are naked.” I cooperated for two pictures, and then we took the Sunday paper back to bed. After we finished the paper, we caught up on

What to Expect,

reading and napping most of the day.

“Look, it says people have sex to relax.” She peered at me over the tops of her glasses.

“I relax to relax.”

“That’s good, because I think we’re both coming down with something.”

I couldn’t get sick; I had to hand the artwork for

Manny’s Cows

over to the editor when she was in Boston in exactly two Saturdays.

W

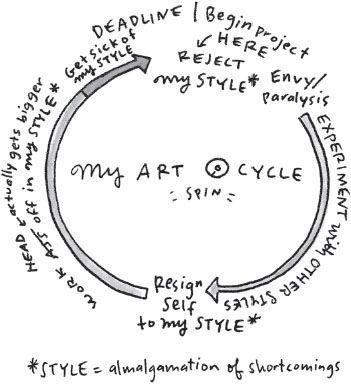

e went over our birth plan with Dr. Bunnell at the thirty-six-week appointment. “So, we don’t want an anesthesiologist in the room,” I explained. “Much easier than refusing their offers,” our birth instructor had advised us. Lorene and I had an understanding: If I asked for pain medication three times, she would find the anesthesiologist.

Dr. Bunnell was on board with the plan. She reminded us to bring another copy, in case she wasn’t with us in the delivery room. Lorene asked if she could “pull” our baby out when the time came and Dr. Bunnell looked at her quizzically. “When I had my son, my doctor asked me if I wanted to, and I reached down under his arms and pulled him out. It was amazing.”

Dr. Bunnell smiled. “Let’s see how we’re doing, but I don’t see any reason why not.”

There was another delicate matter. I brought it up. “There’s kind of a complication with the birth certificate. We want both of our names on it and Steve is okay with that—”

“Steve’s the dad,” Dr. Bunnell confirmed.

“Yep, and he’s going to be around for the birth, but we’ve been told not to mention he’s the dad at the hospital—there’s some sort of professional obligation among the staff to report biological fathers because of deadbeat dads and everything.”

“The birth certificate will go through with both your names?”

“We hope so.” It wasn’t clear. The hospital would send the certificate over to the Department of Health, and according to our lawyer, they were eager to get it. The state hadn’t come up with a policy since they’d legalized gay marriage in the spring. The Department of Public Health would then forward the certificate to legal, and after that it was anyone’s guess. They could sit on it. They could send it straight through. They could attempt to identify a father and make us go through with an adoption. Lorene, Steve, and I found that eventuality depressing; Steve and I would have to sign over our rights so Lorene and I could coadopt her.

I

never got a cold after Vermont, but Lorene ended up with pneumonia. I brought her lunch in bed. “What have

you

been eating?” she asked, brushing the crumbs off my shirt.

“Oh, prenatal deluxe grahams.” I liked to insert “prenatal” in front of any food I ate. “Listen, I’m going to the appointment alone today—you’re staying home—and I’m skipping yoga tonight.” We were now on the once-a-week plan, and this appointment was with the one colleague we had yet to meet. I knew Lorene was really sick when she didn’t object.

Dr. Middleton may have been last, and shortest, but not least. She measured my belly twice. “You are forty-two years old.” I nodded. “You do not look forty-two.” It wasn’t a compliment. “Your baby is small; three to four weeks small. You look so young, no one has been paying attention to your advanced maternal age.” Dr. Middleton was about to make up for it.

“I want you to go to the emergency room.”

Do not pass Go, do not collect $200.

“The emergency room?”

“Your baby may do better outside your womb. Once it’s out, we can take care of it . . . ”

“Can I call home?” She handed me the phone. After I finished explaining, Lorene asked me to put the doctor on. I handed the phone to Dr. Middleton. “Her name is Lorene and she is home with pneumonia.”

“How far away are you?” Dr. Middleton asked. “Well, even if they induce her right away, you should be here in time for the delivery.”

“I don’t think she should drive,” I said. Not in rush hour, not with a fever, not when I was the one who did our Boston driving, but Dr. Middleton had hung up the phone.

I drove myself to the hospital a few blocks away and handed over my file. “Dr. Middleton was concerned about my baby.”

“How are

you

doing?”

I changed into a gown and they put me back on a monitor. No more hiccups.