One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir (37 page)

Read One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir Online

Authors: Suzy Becker

We had dinner out on our way to the airport. Our last romantic dinner for the foreseeable future. We ended up staying until closing time. Our waiter had kids and, like most strangers, he didn’t hesitate to warn us about the mess we were getting ourselves into. “It changes everything—there’s an understatement. Are you ready?”

“I think we are,” Lorene said, relatively confidently.

After we change the wills, winterize the garden, freeze a bunch of dinners . . .

“L

ove the new car,” Steve said first thing, after the hugs were done. I laughed, recalling the one we’d picked him up in the last time.

“We’ve got two new, well, one used-new—” Lorene had opened my coat.

“WOW!” Steve stood, just looking. “Can I?” He placed his hand on top of my belly and let it rest there.

I wonder whose hands she’ll get.

It was a clear night, just like the one we’d had three years ago. Less of a chill in the air. We took our same seats. Three years seemed like such a long time; then again, they were still working on Logan. Steve gripped the handle above the window, a crutch (not a comment on my driving) for someone who was used to gripping a steering wheel when he sat on that side. “I always knew,” he said, pivoting on the handle to face me. “I knew you’d get pregnant.”

I didn’t. I never knew. I wished. I hoped that planning and praying and saying it out loud would make my wish come true, but it was so easy to imagine Steve saying the exact opposite just then.

“She pulled it off,” Lorene chimed in from the backseat.

“You both did,” Steve said. “So, am I sleeping in the nursery?”

“Nursery–guest room. We kept the bed.”

“I was thinking I should probably stay somewhere else after the birth.”

“She won’t be sleeping in your room—”

“No, well, I was thinking more about you two needing time to sort things out . . . ”

“It’ll be we three,” I said. “That’s all the time you’ll have with her for a while, unless, you know, you decide to move next door. Well, next door’s not for sale, but . . . ”

S

teve’s old routines came right back to him. The late-night wanders. Late-morning breakfasts, afternoon dog walks, and late-afternoon snacks. We made dinners together, and as long as there wasn’t a Red Sox game, we hung out in the kitchen until ten or so, then left Steve to his late nights. There seemed to be a newfound comfort, a familiarity (Lorene and I admitted we missed the shrieks; even the dogs didn’t seem to faze him). Or maybe edges had been softened now that we had all passed the pregnancy achievement test.

The Red Sox were in the American League championships. Lorene and I were “closers” (her term)—we could give a fat rat’s ass about the rest of the season, but we never missed a play-off game. I was sure we could get Steve hooked, from a gambling angle, but he couldn’t be bothered to try to understand baseball. He was channeling all of his betting energy into our presidential election, which he couldn’t get anybody else to bother with. On play-off nights he would shut us in the living room to work on his novel and talk on the phone at the kitchen table.

The morning after Game 5, there were two tea mugs in the sink. “Looks like Steve had a late night,” I said to Lorene. She was stacking up his note piles and setting them to the side of the kitchen table.

When I came down for lunch, he was just getting out the juicer to start his citrus routine. “Sleep okay?” I asked.

“I got a few hours.” He cleared his throat, part of the citrus process. “Yeah, look, I’m feeling a bit . . . I don’t know.” He sat down and eyed his piles. “I don’t think this is going to surprise you, I’m feeling a bit stir-crazy. You’re used to being out here in the middle of nowhere, you like it . . . ” He stalled out. I waited, trying to decide whether I was surprised or in denial or whether they were mutually exclusive. “Look, I’m totally dependent on you guys for transport, for everything. I just don’t think it’s good for any of us.”

“I don’t really feel your dependence,” I said, which would explain why I hadn’t gone out of my way to make sure he was having a good time.

“I talked to Bruce last night and he invited me to come stay at his place for a few days or a week or whatever.”

“Oh. So what’s your plan?”

“I’ll catch the tram in West Concord.”

Train, you idiot.

“I could have the baby any day . . . ”

“I want to be there,” he said.

Now that he’d said it, I pictured him

there.

“Did you mean there, like

in

the room?” Reality has always been the problem with my imagination.

“Nah, well, up to you, really. You’ve got Lorene and Meredith.” As he was saying that, I remembered the whole thing about the birth certificate. He went on, “I think I did, but I can’t imagine I’d be of much use. I don’t know what I’d do.”

“You can be right outside, first one in . . . ”

“Yeah, that sounds about right.”

Phew.

A

fter Steve left, I became the pregnant person I’d read about but never thought I’d have time to be. I was sure I’d have a preemie, like myself (six weeks) and Meredith (four weeks) and her son, Henry (two weeks). I thoroughly cleaned the refrigerator and stocked the freezer—cooking, apportioning, packaging, and updating the list of premade dinners tacked to its side. Every day felt like a bonus.

My dad called. “Suetta, what do you think about my flying up this weekend to be there for Tuesday, the big day, right?”

I hated to squash his enthusiasm, but I didn’t need an extra set of expectations hanging around. I pictured my cervix clamping up. “Would you stay at Meredith’s? Dad, I’m not dilated at all. There’s no chance of my having this baby over the weekend. How ’bout I call you after my Monday appointment?”

He decided to stay put. Steve came home for the weekend and he left us with a big pot of his potato-leek soup when he went back to Bruce’s on Sunday night.

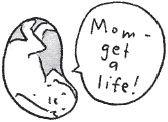

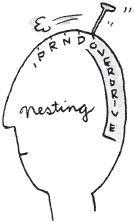

All the women in my yoga class were reading to their unborn babies, which the instructor said was wonderful. I confessed I wasn’t. She encouraged me, at a minimum, to talk to my baby. Out loud.

What if kids have a quota, a number of words after which they stop listening to their parents?

We believe everyone, the developing baby included, has a right to an education. With your help, your child can start life as a successful graduate of our prenatal stimulation program.

D

R

. V

ANDE

C

ARR

Prenatal University

,

Hayward, CA