One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir (41 page)

Read One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir Online

Authors: Suzy Becker

For all its empowerment, natural delivery did not exempt me from the wheelchair exit. I was pushed down with Aurora in my lap, and the three of us waited curbside for our car to come around. The car seat was checked for proper installation, then we buckled our baby in and pulled out from under the overhang into the late-morning sun.

Lorene was driving, checking the rearview mirror every tenth of a mile; I craned my whole self around the passenger seat to look at Aurora every third check.

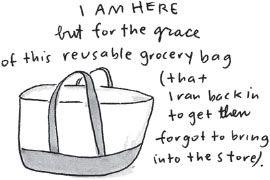

We got off the highway one exit early to pick up some milk and the Sunday

Times

, passing by Hudson Art & Framing on the way. “It’s a girl!” was painted in big pink letters across the windows.

“That’s Ma’s shop, peanut,” I narrated.

Lorene pulled into a parking space to have a closer look. “Geez, it’s Halloween—I completely forgot!” I had, too. It could’ve been spring

or

fall. We could’ve been gone two days or two months.

Lorene pulled back out onto Route 62. A half mile later, a pickup crossed the double yellow line right in front of us, careening up onto the sidewalk—beside us for an instant, then gone. We kept going. “Aren’t you going to stop?” I asked.

“There’s somebody right behind us.” I craned again; the pickup was safely stopped on the sidewalk. We were silent until the next turn. “I’m sorry,” Lorene apologized. “I’m too shaky to help. I just want to get us home.”

“If we had left the shop one second earlier . . . ” In those instants I always conjure up all the near misses we never even know about.

We took our baby and our paper and went straight to our bed.

There were still three hours until the dogs were returned and the dinner guests arrived (with dinner).

We lay there propped up on pillows, with Aurora sleeping between us, and I knew I should have been thinking how our lives had changed forever, so I tried. But it was way too soon to know how, and I preferred feeling as if she’d always been there.

The phone rang. Aurora didn’t stir. Our friend Susan Anker couldn’t hold out any longer. She was coming over. She piled onto the bed and held Aurora as though she was her own, until Aurora started crying.

“Hungry, I think,” I said. “Hide your eyes.” I didn’t care about my ninnies; I didn’t want her to see the hurts-like-a-bastard face I made when Aurora latched.

As I was pulling up my supersize mesh underpants a week later, the absurdity of the idea that we were about to host a naming-day ceremony for sixty people entered my mind, and then exited, embarrassed, as quickly as it had entered. Steve had come home two nights earlier to help us get ready and spend his last few days with his daughter. We collected anointing water from our town’s Little Pond to add to the water Steve brought from Australia’s Port Phillip Bay. Prepared food. Bought wine. Cleaned the house.

Everyone was gathered between the two old maples in the backyard. The sun was warm, directly overhead. Our baby’s first no-hat day. She was in a christening dress that had been in Lorene’s family since the nineteenth century. The three of us stood with Julie, the officiant, facing our guests. Steve, my mother, my sisters, David, and Bruce up front. Then Susan Anker and our friends who had wanted this baby with us—the village that would help us raise our child—gathered behind. The thought, the sun, looking into all the faces, made me well up.

We had just about finished cleaning up and cramming the last of the food into the refrigerator when it was time to take it back out for dinner. Steve’s farewell dinner: leftovers. Aurora was sleeping in the sling. Lorene set the table. Steve put on dinner music.

“Will you take some more photos of me with Aurora tomorrow? Nana June will eat them up.”

“We’ll get you up early; there’s a nice light in our room,” Lorene offered. Steve didn’t say anything. Lorene nudged him. “You okay?”

“Me? Oh, fine. Look.” He pushed his plate away from the edge of the table. “You two’ve got the major adjustment ahead. But leaving is hard. It was hard the last time, and she has a very strong pull, that little one.”

“Oh, c’mon, stay!” Lorene said.

“Please, Daddy?” I whined.

“Stop it! If it weren’t for my parents . . . and Mark . . . Never mind.” He got up to change the music. “Last-night dance party!”

It was only nine, but Lorene and I were ready for bed. Steve would be up all night packing, pacing, having his tea and cereal. We had a few dances and said good night. Then I went back downstairs to give Steve the compass necklace. “We’ll get it when we’re in Melbourne. Or you can bring it back before—” He lowered his head, and I centered the compass on his chest. He had been listening to 10,000 Maniacs.

“Natalie Merchant’s always reminded me of you,” he said.

“She had a baby,” I said. Just like that, without envy, without wondering whether I ever would. “G’night, honey,” I said, and we hugged good night again.

The next morning we got Steve up with us. By 11:30, we had accomplished breakfast, the photo shoot, and the trip to the post office to ship his suitcase overflow back to Australia. Everything was looking good for a one o’clock departure to Boston, making stops at Old Navy for Mark’s presents, and a three o’clock appointment at the hospital, where Aurora’s birth certificate was waiting to be signed and sent back over to City Hall.

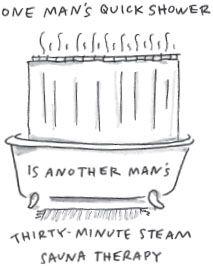

Steve was headed into the bathroom for a quick shower about the time we were sitting down for lunch. “Listen, don’t worry about me, I’ll make myself something, or I can always grab a bite at the airport.” He was still in the shower when we rolled Aurora out in her all-terrain stroller for a walk with the dogs.

A little before one, we got back and Steve was popping a couple of pieces of bread into the toaster. He got himself a plate and had a sit-down lunch. I went upstairs to change Aurora.

When I came back, Steve was reshelving his lunch makings in the fridge. He slinked by in his slippers to finish up his packing. “Don’t say it. Don’t say it; I’m hopeless. I’m just not very good at these transitions, you know.”

It was three on the dot when we arrived at the hospital and valet-parked the car. “Want me to stay down here?” Steve offered.

“Maybe they’ll add a third line to our certificate,” Lorene said, and pulled him onto the elevator. It was a nonappointment, nonevent; someone asked our baby’s name and handed us the birth certificate. We signed and handed it back. Our mute tagalong smiled.

“You okay with it?” I asked Steve when we were a few blocks from the hospital.

“No question. You two

are

the parents. I would have absolutely no idea what to do with her at this stage.”

“You’d figure it out,” I said. “Feels kind of dumb, inadequate, saying it again, but . . . thank you.”

“Thank

you.

You’ve changed my life. Made it much better, really.”

We killed some time at the airport, lingering this side of customs. Then Steve walked backward through the passageway, waving until we could no longer see him.