One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir (17 page)

Read One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir Online

Authors: Suzy Becker

I forgot all about the prescribed visualization.

“I may only have one tube—”

“One’s all you need.” She squeezed my toes. Lorene gave her a hug. “Lie there as long as you like, and take it easy the rest of the day. Schedule a pregnancy test for two weeks and call us if you have bleeding before.”

Lorene drove us home. I maintained a pelvic tilt, my feet on the dashboard, until the ride was over. We had a whole sunny Sunday and Labor Day Monday ahead of us.

That afternoon we loaded Vita, Mister, and Mister’s brother Hooley (ours for the weekend) into the back of the Subaru and went for an easy walk along the Nashua River. Five minutes from the parking lot, there was a loud cracking off to our left and we watched an old tree uproot and fall, slow motion, into the river. We stepped around the pile of sandy dirt where the roots had been and kept going.

A quarter mile later, we heard an ominous growling sound. I picked up the pace (not even close to running), and we came upon Hooley. The two flat-coat retrievers had been swimming. Mister, at sixty-five pounds, was scurrying up and down the banks. Hooley, at a hundred pounds, had gotten himself stuck in the mudslide he’d made of the bank. I reached for his collar and pulled; the force of his coming unstuck catapulted me into the river.

“My body really didn’t panic,” I found myself explaining to Lorene as I was walking back to the car in my soaked clothes. “I was surprised, probably a little shocked by the coldness of the water, but . . . ” I was not in zygote expulsion mode. Was I?

“Don’t worry; besides, there’s nothing we can do about it.”

For the next two weeks, I tried to remind myself that people had remained pregnant under far more abusive circumstances.

I just wouldn’t have been one of them. I got my period, done in by the Nashua River.

I

turned forty in Vermont a few weeks later with Lorene, my sisters, Bruce, and the dogs. It felt like putting a period (not that kind) on the end of my thirties. I was happy to have the brain surgery and dating behind me. I had a feeling of fullness—love, stability, contentment—that kind. So I didn’t get pregnant in my thirties. Forty is only a couple months’ difference.

We tried again in October. My brother called halfway through the waiting cycle for my belated birthday. “I wish I could help, Sue-Sue. I have to be careful—I sneeze on someone and they’re pregnant.”

“You’re supposed to sneeze into your elbow now.” I was feeling optimistic at that moment; my boobs were swollen.

Pseudocyesis

Sympathetic

or

False Pregnancy

The erroneous notion of carrying a baby. An individual experiences all prevalent symptoms, except for presence of fetus.

Documented in:

• females bearing strong desire to conceive

• male partners of pregnant women (also known as

couvade

)

• dogs, pandas, and other animals

Five days later, I got my period. This time there was no one, no incident, nothing else to blame. I looked at myself in the mirror.

I decided to grow my hair out, go for something more maternal. Lump the awkward-hair stage and the no-exercise-writing-a-book-butt stages together. I called Lorene to tell her my news—period and hair—and went back up to work.

An hour later, my sister Meredith let herself in the kitchen door. She called up, “Bad timing?”

I came down. “No . . . or yes. I just got my period.” She hugged me. “Ow! My boobs!” I held on to her and cried. “I’m sorry. I didn’t realize I was this upset. Did you have a meeting out here or— ?”

“This is bad timing,” she said. All of a sudden, I knew. “I’m pregnant.”

I’d imagined the scene at least a hundred times, except I was pregnant, too. “Oh my gahh!” I hugged her again. I

was

happy for her. “Wow, I didn’t know, you didn’t tell me you were trying.” We were so busy talking about my trying.

“We weren’t really, I mean, we were getting ready to. I was sure it was going to take forever,” she paused. “The baby is due on Dad’s birthday.”

I could never match that. “Want some coffee, no, wait, you can’t drink coffee, tea? Water?” She had to go; she just wanted me to be the first (after Jonathan) to know.

I went back up to my studio, as if I could work again, and cried some more. Everyone was getting pregnant—my doctor, my friend Michaela, my sister . . .

Why does it have to be so hard for me?

Things could be worse . . .

It took Japan’s Crown Princess Masako eight years to get pregnant and then she gave birth to a girl, which was considered a failure. (Her imperial duty was to produce a male heir.)

I went back to work, looking forward to the glass of wine Meredith would not be having with her dinner.

I

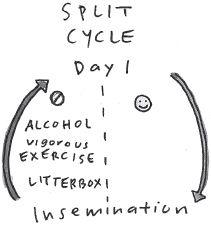

n December, after our third try failed, we had another meeting with Dr. Penzias—the why-it-isn’t-working meeting. “Call it system design, or error: eighty percent of the time, between healthy, fertile couples in their reproductive prime, it doesn’t work. Simple as that.”

Nature’s contraception.

“Your age is a factor, we’ve got a possible tube issue—but we want to do better. We

can

do better. I’m going to write a letter to your insurance company and see if we can get that infertility diagnosis. We could start the hormones this month.”

We couldn’t. And I was disappointed. Now I

wanted

the infertility diagnosis; like the gynecologist had said, “It doesn’t change anything.” We want to get me pregnant.

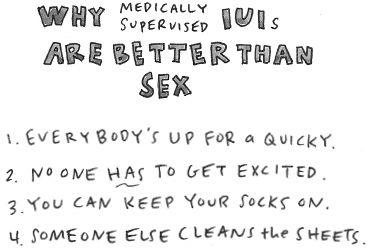

“What about the two tries at home?” I asked the insurance liaison, the bearer of bad news.

“You can take it up with them yourself, but I’ll tell you ahead of time, even if you had documentation—they rejected one of our client’s claims. She had all of her sperm-bank receipts. They said it had to be an in-office, ‘medically supervised’ procedure. She yelled at them, ‘What do you think I’m doing, drinking it?’ They didn’t budge.”

We had Jackie the inseminator again for our fourth try. She was wearing a Santa cap but there was no ho-ho-ho to go with it. I was a success-rate spoiler. She looked at our paperwork, then she looked at us. “Why are you using just the one vial? Most people do two, at least two.”

“They do? Can we? Let’s!” we said. We weren’t buying it by the vial; it made complete sense. Steve had deposited ten at a whack.

Why didn’t you mention it the first time?

“I can’t, it’s too late for this insemination. Something to keep in mind for the next time.” She’d already written this time off.

We minimized our table time; Lorene had to get back for work. We assumed our positions in the car—Lorene at the wheel, my feet on the dash—and rolled out of the garage. Lorene wondered out loud, “What else don’t we know?”