One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir (19 page)

Read One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir Online

Authors: Suzy Becker

L

orene printed out the website’s injection instructions and read them out loud as we drove in for our information session. We sat down at a long table, just the two of us. We

were

the information session.

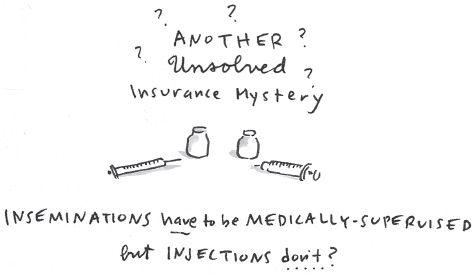

The injection itself turned out to be the least of our worries. First, the hormone powder had to be mixed with sterile water. Then everything had to be sterilely transferred from one tiny glass ampule to another, using needles and syringes.

Lorene practiced the injection in a rubber cork. “That’s all there is to it,” the nurse said, smiling a Friday-four-p.m. smile and disposing of the syringe in the biohazardous waste box. “Do you want to try again?”

I looked at Lorene. The nurse added, “It’s all written down. There’s a video on the website, and you can call the on-call doctor at any point in the process . . . ”

Lorene said, “I’ll try it again.” I felt myself relax.

“Have you ordered your FSH?” the nurse asked me while Lorene was mixing the fake stuff.

I launched into our delivery dilemma as I was signing her orientation attendance. “The pharmacy’s right in this building, you know, you could just pick it up.”

The pharmacist handed us our shopping bag: the FSH, sterile water, syringes, needle/biohazardous-waste “sharps” box, a purse-size cold-pack carrier (free gift from the makers of Gonal-f FSH), and I threw in my Cow Tale that I’d purchased from their small candy selection.

Sunday night, we headed upstairs around 9:30. We planned to retire with the paper after our first injection. Lorene laid out the written instructions, the ampules of FSH and distilled water, and the syringe on the windowsill. She calmly mixed the FSH and drew it up with the syringe. I lay on the rug. She knelt down and leaned toward me. Misplacing the intimacy of the moment, I thought she was going to kiss me. Instead, she lifted my shirt and rubbed my belly with an alcohol wipe. “Yow! Cold!” I complained.

“Baby!” she laughed and reached for the syringe. “Okay.” She uncapped the needle, pinched my belly skin, and announced, “On the count of three, you’re going to feel a sharp prick. One, two . . . okay. Okay, just a second.” She looked at the tip of the needle over the tops of her glasses. “All right. Ready? Okay, one, two . . . ” She looked at me. “Do

you

want to do this?”

Me?

I couldn’t get my finger to stay put when we had to do the finger-prick blood test in high school biology. “All you.”

“I hate needles. Hold on a minute.” She took a deep breath. “Okay, this is not going to give you cancer.” She started over with the skin pinch. “Here we go. One, two, three.” Done.

“Thank you.”

“You’re nice to say that,” she said.

“No, I’m really grateful. I’m so glad I’m

not

doing this alone.”

She lay down on top of me, then pushed herself up suddenly. “Oh, God, does it hurt?”

“Not a bit.” She went downstairs and poured herself a whiskey.

C

ANCER

C

OURT

2020

J

UDGE

:

Your wife was concerned. How about you? Did

YOU

ever think about what she was injecting?

M

E

:

Like what was in it? Mouse pee or hamster hormones or something? At that point, it seemed like our only option. And I trusted Dr. Penzias . . . a doctor wouldn’t let you harm yourself.

(Courtroom laughter)

J

UDGE

:

Order! (

Laughter dies down)

J

UDGE

:

Was

NOT

getting pregnant an option?

We kept up our 9:30 nightly; we got the one-two-threes down to two. On Friday morning, we incorporated the blood work and ultrasound monitoring into our early-morning routine. The two of us would flop into the car, no shower, no breakfast; the inconvenience never even had a chance to register in our uncaffeinated state.

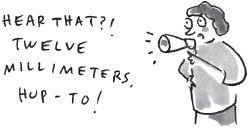

I was just starting to wake up when I was in the ultrasound room. The technician provided live commentary on my follicles. “One on the left ovary, lots of good-sized ones coming along. None on the right, a handful of up-and-comers.”

“What’s a good-sized-one?”

“We like to see them larger than twelve millimeters.”

We received our updated injection instructions by phone that afternoon: Stay the course. More monitoring on Sunday.

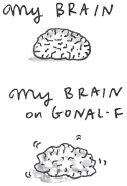

I had a hard time differentiating the effects of the hormones from other inputs, like the added stress I experience working on a new job. My first cartoon for

Seed

magazine was due in a week. I’d submitted three sketches and hadn’t heard anything, so I Gonal-e-mailed the editor. She called the next day to say she liked all three, and she’d decided on one, with one small change: “Can you make the scientist look less like a stereotypical scientist? We’re trying to make science sexy here.”

She called the next day to say she liked all three, and she’d decided on one, with one small change: “Can you make the scientist look less like a stereotypical scientist? We’re trying to make science sexy here.”

“You want a hubba scientist?”

“Yes,” she laughed. I drank a big glass of water, gave him a new head, and faxed it off.

I actually felt the effects of hydration—going from zero (not counting coffee or lettuce) to sixty-four ounces—more profoundly than the hormones. After a lifetime of proud public-bathroom avoidance, I was reduced to making pit stops on my way into Boston.