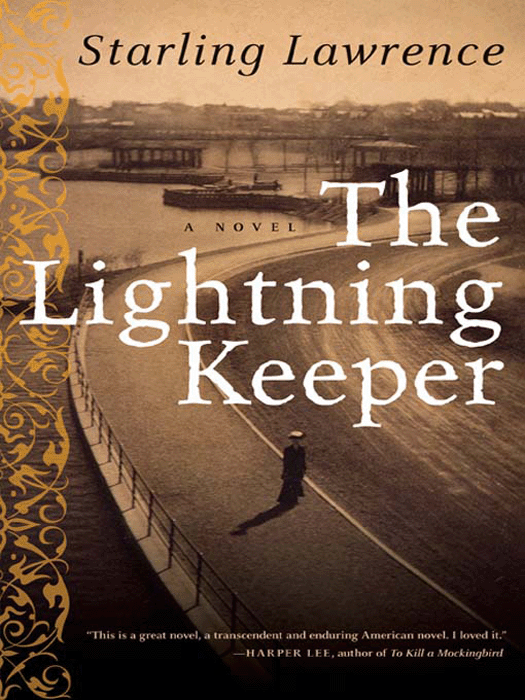

The Lightning Keeper

Read The Lightning Keeper Online

Authors: Starling Lawrence

A NOVEL

for Jenny Preston and Earl Shorris

in memory of Linda Corrente

I have always hated my name, though perhaps I didâ¦

It had begun to snow, and she had been sittingâ¦

It was, as Stephenson had said, only a machine, andâ¦

No account of the so-called North West Corner, and certainlyâ¦

He was shocked by the temperature of the water. Beyondâ¦

In the weeks following the arrival of Stephenson's letter, theâ¦

As Chapman puts itâ¦

Toma's dream was so pleasant that he awoke laughing. Heâ¦

From certain signs, including Horatio Washington's virtual disappearance from theâ¦

“â¦and although I am flattered by your reference to theâ¦

The wooded environs of Great Mountain are a most pleasantâ¦

Toma slept for most of the train journey from Beecher'sâ¦

I write in the understanding that the arrangements between Generalâ¦

The summer of 1916 was a time of feverish activityâ¦

From his new residence in the Bottom, it took Tomaâ¦

The colorful place name is catnip to the amateur historian.

When she heard the thump and the wailing cry, Harrietâ¦

Despite her careful plans, and her middle-of-the-night revisions to thoseâ¦

The desk in the office of the now defunct Bigelowâ¦

Although the sun was now so bright and hot thatâ¦

“My friends, you have heard the introductory remarks from our

Much has been written and still more said concerningâ¦

I have always hated my name, though perhaps I did not even know that until I told him what it wasâHarriet, I said in a loud, clear voice because he was foreign and I thought he might not understand unless I spoke very distinctly, even though he had addressed the question to me in what seemed to be unusually good Englishâand he simply looked at me for a moment, and I began to think he really

hadn't

understood me. It was quite oddâ¦he was looking at me but not really looking at me, or at least not seeing me, and for all I knew he was an idiot or a madman as well as a foreigner, though I'm sure I didn't feel afraid. I felt so strange, as if I weighed nothing, as if he could lift me up by the very power of his eyes alone, do anything at all with me, and yet I was not afraid. I was a child, or barely more than a child, and what does one know of such things at the age of fourteen? And yet I did know. What he said when he finally found his voice was simply this: It doesn't sound like you. I hadn't the faintest idea what he was talking about. I wanted to hear him speak again, and so I said, in a more conversational tone this time: If you do not understand I shall spell it for you. I was trying to provoke him, to show him that I was something more than a child to be trifled with. And he laughed, meaning no harm, and his laughter was the most beautiful sound I had ever heard. When I had spelled it out, he said: “H” is enough: that is what I shall call you, until we find something better. And when will that be? He just smiled and shook his head. And how will you find me, I asked, if I do not even live in your country? (How was I to know, then, that he was anything other than an Italian boy, like all the rest of them there on the docks of Naples, trying to earn a few pennies by carrying baggage?) Said he, I

am bound for the New World; you may count on seeing me there.

I very nearly neglected to learn his name in all this discussion of mine, and I forgot to worry about Mama, who had such a coughing spell right there in the customs shed, and was taken away by Father in search of the port physician. He was half carrying her, and something dropped from her hand. When I went to see what it was, I was horrified to find my initial, H, embroidered there in the linen, which was filled with blood. I had forgotten that I had given it to her, and I had never seen the blood before, as she was careful about hiding all trace of her illness from me. And perhaps I took this as an omen: there was my name, H, on that ruined handkerchief, and I wouldn't touch it at all.

We sat there for well over three hours. Father glared wildly over his shoulder at me as he was leading Mama away and he said: Don't you move from this place. And the boy and Iâperhaps he thought Father meant him tooâstayed with the luggage through the afternoon, finally taking seats on two upended cases. And some of the other boys who had crowded around the ship came by out of curiosity, and one of them made a sign, rubbing two fingers and his thumb together to mean money or perhaps something vile, and Toma, as I had now learned his name, stood and fixed his eye on them and they all ran away.

An officer of some sort came after a while and asked some questions in really dreadful English, and then he came back with a cup of tea for me. I asked him would he bring one for my friend, and the man looked very put out, but he did as I asked. So we had a tea party and we talked, though there were long periods of silence between us that were not unpleasant at all. And I wondered, What is happening to me?

Father came back at last, and Toma supervised the transfer of the baggage to the hotel. He wouldn't take anything from Father, nothing at all, even though he must have expected to be paid when he first caught our eye coming off the ship. It filled me with pride that even now makes me blush: He did this for me, I said to myself. I'm sure I wasn't wrong about that. What other reason could there be? And I was as proud as if he had laid his cloak in the gutter for me. I had read that in a book.

Mama recovered in a week's time, and every day when I went out walking with Father, there was the boy, sitting against the wall, waiting for us. He impressed Father with his English and with his whispered

caution about walking unaccompanied in such a place as Naples. Father must have wrung some confirmation of this lurking danger from the hotel management, for he did not object to having Toma follow a couple of paces behind us. He was only sixteen at that time, but you would never have thought it to look at him, and you certainly would have thought better of offering him any provocation.

Poor Father was no traveler, and certainly no linguist, and he was very much caught up in nursing Mama back to health. If he needed something he was likely to send Toma to the chemist or the lace maker for a dozen handkerchiefs rather than bother the staff at the hotel, as they tended to get things wrong. He was ever impatient in the matter of details, and had a difficulty in conveying, in any language, precisely what he meant.

Well, there are other ways of conveying a thought, a meaning, an emotion too teeming and urgent for words. And as we walked, sometimes to the esplanade by the bay, sometimes to the museum to see the charming mosaics and those disturbing great torsos of the naked gods, he would walk behind us, never speaking unless Father asked him a question, but with his eyes boring into the back of me, consuming me. Every so often I would contrive to turn in order to catch this gaze, to reassure myself that I was not imagining things. He did not try to hide his interest or avert his eyes, except of course when Father turned as well. Sometimes he was smiling, an expression I imagine he wore before I turned to look back at him; but more often there was a thoughtful, even a sad aspect to his features, which I could not understand because looking at him made me happier than I had ever been. So happy, and so confused: it was a week before I dared to write in my journal that I was in love.

A love unconsummated and unspoken, but there was fuel enough for the fire, fuel to keep it burning, banked and all but forgotten, for those six years when I saw nothing of him, heard nothing, did not even know if he had arrived safely in this country or perished in the hold of some pestilential steamship, as so many of those immigrants were said to have done.

My mother did recover her strength, almost miraculously, and I think it was as much an effort of will as anything else, for she so wanted to see the murals of Pompeii and even more the excavations of Hercu

laneum, that city buried for centuries in the volcanic mud. My father did not care at all about such things, and consoled himself in the absence of work by scanning the papers for quotations on the price of steel and pig iron. But he did care very much about Mamaâher health being the whole reason for this tripâand was ready to humor her least whim. So he arranged for a motorcarâI sometimes think this was the only device of the present century that interested him at allâand we made a holiday outing of it, with a picnic hamper and bottles of chilled wine. With the driver, all the seats in the car were taken, and so Toma rode on the wheel well, lying wedged between the fender and the motor. And by feigning great interest in the passing countryside and the road unfurling ahead, it was now I who had the luxury of devouring him to the last detail: the clean line of his neck descending into the ballooning collar, the angle of his wrist and corded arm as he held fast to the chrome bar supporting the lamp, that torsoâmore like a god than anything I had seen in the museumâlimned in the fluttering material of his shirt. Mother put her hand on my shoulder and drew me back into the protection of the car, saying that the wind was making my face quite red.

We first visited Pompeii, with Mt. Vesuvius as a backdrop sending an innocuous plume of vapor up into a clear blue sky. The brightness of the day made the interiors correspondingly dark, and in one such turning, with my parents lingering for a moment in the previous chamber, admiring the burnt marigold of those walls, I tripped on a piece of fallen masonry, and Toma reached out and caught me. I needed only the slightest touch to regain my balance, and had I put my hand to a wall it would have sufficed. But there was his bare forearm, and mine suddenly lying lengthwise upon it. I experienced a shock, as if from electricity, or as if I had been touched by lightning, and my hand closed in reflex upon that warm unyielding flesh. I must have gasped, for my mother called out to me, and I replied, still holding fast to Toma, that it was nothing, I had merely stumbled.

How much darker and more mysterious the labyrinths of Herculaneum, a city entirely buried in the same eruption as Pompeii, and just now being excavated inch by inch from the thirty-foot layer of hardened mud. Everything there must be seen by torchlight, and Father grumbled at the extravagance of having so many lit in our honor. And

it was in a far chamber where the gorgeous marble of the pavement swam and shimmered in so many colors that Toma kissed me. I was standing on the step to a bath so that our faces were very close when I turned and the embrace seemed the most natural thing in the world. Then he folded me into his arms and put his face into my hair, where he whispered a sound, or a foreign word, or even a name, though I know it was not mine. And just as I was puzzling over this, with my heart likely to burst within me, I heard my mother's footsteps on the marble, and she called out: Do be careful, dear, one never knows in such places. And Toma moved silently to the far side of the room.

My mother was no fool, and I have the impression that she watched me more carefully after Herculaneum. At any rate I had no more chances to be alone with him, and that was the thing that I wanted above all else. He had drawn me to him, and I seemed to have no will toward anything or anyone else. I did not know exactly how long my parents planned to stay in Naples, nor Toma either, and a feeling of desperation closed over me. I dreamt about Herculaneum and Toma, and slept badly. My mother thought it might be my time of the month, and framed a careful question. No, I said, it is not that. From the way she looked at me I knew it would have been better if I could have spoken that lie.

My mother slept very lightly, perhaps on account of her illness. One night I was having an astonishingly vivid dream about Toma, a dream full of incidents and images of which I had no experience, not even an inkling. We were in a river together, and he had taken away my clothes, and I was not ashamed. I was calling his name, calling him to come and touch me, touch me, for I had literally no idea of what men and women actually do in such situations. And he was touching me, and the river was flowing around and through us with the most exquisite sensations, when I heard a harsh voice in my ear and felt a harsher hand on my shoulder, shaking me awake.

I had indeed been calling to Toma, and this had roused my mother in the adjoining chamber. But it was I who had taken away those clothes, or fought free of the bedding, and I who touched myself.

Get up, hissed my mother, and she dragged me to the bath, gasping for air herself. She placed me on one of those indecent porcelain fixtures that the Europeans use for washing themselves instead of bathing

properly, and she hitched my nightdress up above my breasts and told me not to move. I closed my eyes for shame so that I would not have to look at my own body. She went into the sitting room, where there was a bowl of melting ice that had chilled the sherbet for our dinner, and this freezing mixture she threw upon my belly and thighs, quite taking the breath from me. My humiliation was almost complete. Then my mother, who had always been so gentle with me, seized me by the hair and told me that I must never again touch myself. Did I understand? I nodded, although I had no comprehension of what I had done to offend her. She kissed me then on the forehead and told me to dry myself and go to bed. This was the first and only discussion of love that I ever had with my mother. Perhaps we would have had them, but she was dead within a year of our return from Europe. And what do I now know of love, except for this one moment? I have been married, and am now a widow, and I have never found the way back to that beautiful place in my dreams.

I do not believe that my father's sleep was disturbed by this drama. The next morning my mother managed to put in front of him an English newspaper full of speculation about the crisis in the Balkans provoked by Austria's annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In my wretchedness I took satisfaction in the mere recitation of those names, for I knew that Toma's country, Montenegro, was the neighbor to these, and the Austrians his sworn enemies. It was the opinion of this newspaper that war was imminent, and so my father found us passage on a liner leaving for New York the following day. We barely had time to pack, and I did not see Toma before our departure. I thought I would never see him again, and so I took a terrible risk and gave all my pocket money to a porter, who barely comprehended a word I said. Somehow I made him understand that he was to take my note of farewell and deliver it into the hands of the beautiful boy.

âfrom the diary of Harriet Bigelow Truscott, on the eve of her marriage, September 12, 1919