The Lightning Keeper (2 page)

Read The Lightning Keeper Online

Authors: Starling Lawrence

ONE

It had begun to snow, and she had been sitting in the car for so long that the snowflakes, such extravagantly grand and varied snowflakes, fixed themselves to the dark green cowling, like butterflies pinned to a board, for the motor was now as cold as she was. Her watch had stoppedâit was a pretty, unreliable thing, no more than a piece of jewelry against the dark silk of her dressâand she did not know quite what time it was, only that the meeting between her father and Mr. Stephenson had been fixed for half past two in the afternoon, and they had driven at an immoderate speed down from Beecher's Bridge that morning, with her father wedged in the back by the great half-moon of iron, urging the driver to hurry.

MacEwan, a dour man in any circumstances, shrank into the collar of his coat and muttered to himself.

“What's that you say, MacEwan?” Her father must have seen rather than heard the remark, for his hearing was now reduced to the point where the only sounds that animated his reflections, other than conversation directed at him in very emphatic tones, were the thump and wheeze of the tub bellows at the Bigelow Iron Company or the clear ringing of the trip-hammer as it fell to the anvil, pounding, shaping, and purifying the glowing metal into bars. It was not much of the universe, Harriet thought, when compared to her own appreciation of music, quiet conversation, even the sound of a brook, and she knew, because her father had told her, that he once recognized and took

pleasure in the songs of many birds, particularly the black-throated green warbler in the spring, and the cry of the loon in autumn, far away on the lakes of Great Mountain. It was fortunate, she thought, that the sounds remaining to him, the bellows and the hammer, were so deeply reassuring.

“I said, sir, it's no use asking me to go faster than the Packard wants to go, without it'll come to some harm. And that's a terrible weight of iron you've got on that seat with you, sir.” Which indeed it was, and MacEwan had the grace or sense of self-preservation not to reiterate his point when the Packard experienced a puncture of the rear left tire, the one directly under the iron wheel, or piece of a wheel, that had been loaded into the car just before they left the Bigelow works.

Looking at the light now, and allowing for the snow, which made the day both darker and brighter, she guessed that it was sometime after four o'clock, an hour etched in her mind by virtue of the whistle blast marking the end of the shift in the furnace and forge. The eye knew that hour in all seasons, and the stomach too. What would she not give now for a cup of tea? She had not eaten since breakfast, and so it was not just the bracing warmth that she imagined but the odor and texture of iced seed cake, a fat slice of it, or a sandwich of any description, even a crust of unbuttered bread. Father had promised her a fine dinner at Delmonico's as soon as he had finished, had talked Stephenson around to his proposal, and he didn't imagine that would take very long at all. So if you'll just sit here like a good girl?

She had felt a burning in her cheeks when he said that, and had almost made an answer. At any rate she had turned sharply in the direction of this remark and found herself staring into the face of the fellow trying to shift the iron wheel off the seat and out of the car, a well-fleshed, confident, and not unattractive face, which, by dint of exertion against such a weight, matched or exceeded the rising color of her own. There were two of them struggling with the wheel in that awkward space, joking under their breath about how the old fellow could only make half a wheel at a time, and when the man caught her misdirected glance he grinned and evenâwas she imagining this impertinence?âwinked at her before taking the entire burden of the iron onto his flexed knees, turning, and heaving it clear of the car with an explosive grunt.

Like a good girlâ¦she could make herself blush simply by repeating the words. Her father often spoke to her thus, out of distracted affection, and she did not mind it. There's a good girl, he would say, perhaps in acknowledgement of a piece of toast. But today she minded very much indeed, particularly as the automobile trip from Beecher's Bridge to New York City, with the urgency of time and the anxious interruptions of the blown tire, was hardly an opportunity to discuss what would be said, what must be said, to Mr. Stephenson. She had hoped her father would remember that she wanted, and out of no mere vanity, to be included in this discussion on which the fate of the Bigelow works very likely hung. Perhaps she had not spoken loud enough, or been sufficiently assertive? Or perhaps her father simply had not wished to hear.

It was Harriet who had brought to her father's attention the item in a trade journalâ

Iron and Steel News

âabout the John Stephenson Company's contract to supply two hundred and eighty-five new subway cars to the IRT.

“Isn't that the same Mr. Stephenson who once took us to the baseball game?” she asked, putting the magazine by his plate. Yes, he thought that very likely, and a few solemn forkfuls later he wondered how old Stephenson might be getting on.

“Getting on very well indeed, by the sound of it,” Harriet replied, wondering how many wheels each of those many new cars was to have. “You don't suppose⦔

“Suppose what, my dear?” Amos Bigelow was very little inclined toward supposition or abstraction of any kind.

“I was wondering where Mr. Stephenson would get all the wheels he will require. Have you not done business with him before? Was that not why we went to see the baseball?” Of the game she remembered nothing but the fierce roar of the crowd, the pitchers of beer consumed by her father and the jovial Stephenson, and an enormous concoction of spun sugar that had later made her ill. The next day her hands were swollen from clapping so hard and so long in her effort to please.

“Well, I don't remember exactly whose idea that was, but yes, certainly, I've known Stephenson for thirty years, and I should think he knows me. Let me read this now.”

Her father warmed to the idea of those wheels, then appropriated it as his own, and soon it grew to the proportions of a mania. He would not willingly entertain other topics of discussion, nor could Harriet qualify his enthusiasm for the project by any normal business consideration such as costs, scheduling, specifications, and possible modifications to the plant. The Bigelow Iron Company would manufacture the wheels as subcontractor to the John Stephenson Company; he and his old friend would see to that. There was no arguing with this proposition that bloomed so suddenly in his mind with no encouragement, correspondence, or information from Stephenson, who could not have known how things were progressing in Beecher's Bridge. The contract, and its successful conclusion, became a fixed star in Amos Bigelow's firmament, and to express reservation or even to ask too many questions would have been as offensive to him as standing on the broad porch of the Congregational Church after the service and entertaining doubts about the existence of God or the certainty of eternal salvation. Her father was fifty-nine years old, but sometimes he seemed much older than that, and she wondered whether he had always been soâ¦mercurial, and whether his judgement now was perfectly sound.

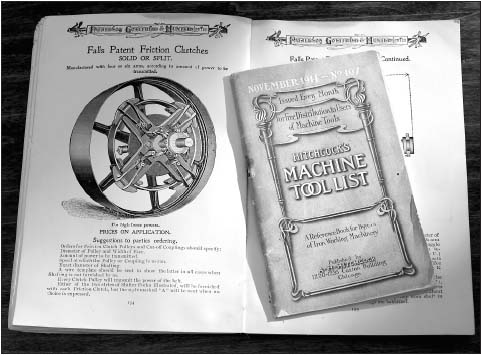

Amos Bigelow became obsessed with catalogues, and where he might once have spent the better part of his day prowling the furnace building or engaging Horatio Washington in discussion about repair or modification of the breast wheelâthe waterwheel was a source of endless concernâhe now spent his time perusing and annotating Hitchcock's Machine Tool List, or the Patterson, Gottfried & Hunter catalogue of power transmission devices.

Harriet, who attended to the ledgers at the works, noted the changed composition of the mail pouch and formed in her mind grim auguries of the future. Her office, no more than a cubbyhole, adjoined that of the ironmaster, and sometimes he would call out to her to come look at this splendid object, a double-arm split pulley on the Reeves patent model, or this Walcott & Wood turret lathe. Harriet looked, and was as enthusiastic as she could be, but what always caught her eye on the page was the price of these devices. She asked, as if she did not know, what use the Bigelow Iron Company would make of such things. But her father's enthusiasm for the Stephenson project knew no

bounds or measure, and even today, when they had been so anxious about the time, he had made MacEwan stop the car at Park Avenue and 142nd Street so that they might admire the Patterson, Gottfried billboard and the model, looming out of the muddy expanse of pasture, of what was proclaimed the largest wood pulley on earth.

Harriet had undertaken the actual correspondence with Stephenson, though her father seemed to believe that he had already broached the business and received a reply. She showed her father draft after draft to reflect the refinements and reservations suggested by Horatio Washington and Mr. Brown, the foreman of the furnace, both of whom expressed doubt that so many wheelsâher estimateâcould be produced on any tight schedule. It was Horatio who pointed out that there hadn't been much snow this winter, and the holding ponds up the river on Great Mountain were already low. Come August, who knew what they'd be using for water.

Stephenson's responseâto Amos Bigelow, of course, rather than Harrietâwas cordial but not very encouraging. Yes, he would be subcontracting the wheel assemblies along with many other items in the undercarriage and couplings, air-brakes, upholstery, and of course the electrical systems. The John Stephenson Company's long experience in the construction of public conveyancesâfrom New York horse cars in the old days to railroad carriages in Hong Kong and New Delhiâhad given him the advantage in this competition, and while he could certainly manufacture the entire subway car, it was not practical given the constraints of time. Certainly he remembered the pleasant association with Bigelow over these many years, and he had never heard the slightest complaint about any of Bigelow's products. Come to think of it, he had received a letter not long ago from the maintenance department of the Boston & Maine Railroad inquiring into the availability of certain items of renovationâbrass fittings and upholsteryâand commenting, parenthetically, on the durability and excellence of the wheels, even after so many years of service. Rolling stock, after all, was no better than its wheels, however fancy the hat racks and the paint job might be.

“What an excellent fellow,” exclaimed Bigelow, relishing this paragraph of the letter. “I couldn't have put it better myself.”

That compliment delivered, Stephenson went on to say that he had already been in discussion with several foundries on the subject of

wheels, and so it would come down to the matters of price and specifications: it was not yet clear whether iron wheelsâgranting the excellence of the Bigelow productâwould do, or whether he must turn to the steel available from the open-hearth operations in Pittsburgh. It was a complex decision, and he would be in touch when he had further information. There were, of course, other subcontracts to let: had the Bigelow works any experience in the manufacture of springs?

Finally, all of this was on hold for now, as the commissionersâfollowing a fatal derailment in the Steinway Tunnel and acrimonious debate in the city councilâhad announced that an entirely new list of specifications would be forthcoming to assure the safety of workers and passengers, to restore public confidence in the most extensive and modern metropolitan subway system in the world, embracing not only the island of Manhattan, butâ¦etc. When they finally got down to brass tacks and issued the new specifications, the guessing would be over and the race would be on.

The correspondence had been the occasion for Harriet's sudden education, her real education, in the ways and workings of the Bigelow Iron Company, from the blast furnace itself and the foundry, where the metal would be cast, through to the forge and hammer shop, where the collars and bolts would be fashioned, and finally to the grinding and finishing operation. She knew things well beyond the payroll and expense ledgers that had been her original responsibility, knew things that her father certainly knew well enough in his bones from all those years of experience, but not well enough to express in writing, much less in discussion with so careful and expert a man as Stephenson. She knew the quantities of ore, charcoal, and limestone flux necessary to produce a ton of pig iron; she knew the temperature of the furnace and had studied the results of the chemical assay of its product; she knew how many revolutions per minute Horatio's great waterwheel was capable of, and the cost of each abrasive grinder and lathe chuck in the finishing shop. And she knew that she could tell Mr. Stephenson, in the fewest possible words, what the Bigelow Iron Company could and could not deliver.

She had been educated in unexpected ways as well, for the workmen were not accustomed to having a woman anywhere in the vicinity of the furnace or shops. Sometimes they didn't know she was there; at

other times, by force of habit, they let slip indecencies that they would never have uttered at home, but which must be, she thought, the common currency of that workplace. Horatio, whom she dealt with almost every day, had expressed his violent scorn upon reading Stephenson's letter.

“Springs!” he said, followed by an epithet linking the place of eternal damnation to an adjective of the most appalling coarseness. She had heard that word once or twice before, and she knew exactly what it meant. Horatio, as shocked as she was, spat to cover his embarrassment, then turned away. She had spoken to her father about it, hoping to introduce the idea of some morally uplifting influence on the workers, particularly Horatio.

“Well, what did he say to you?”

She made no reply but set her shoulders in annoyance at the stupidity of men. Nothing in the world could force her to repeat those words.

“Harriet, never mind. I'm sure he meant no harm by it. I'll try to speak to him, but it's an ironworks, you'll remember, not a Sunday school, and it wouldn't do to upset him or any of them with all the work ahead of us now. He lives down there, you know, down below, Horatio and that woman of his. I don't even know that they are married. Black people have their own ways, but I'm told she goes to church, the other church.”