One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir (13 page)

Read One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir Online

Authors: Suzy Becker

Back in August, the three of us

had decided to go with an instate sperm bank over the California competitor. Convenience beat conviviality. We had filled out all the paperwork. Steve had passed all the tests in advance (they had waived their upper age limit), and we were screened in for the “anonymous” donor program, which doubled as their “selected” (as in unwed to donee) donor program.

Anonymous Donors

a.k.a. altruistic men willing to “help couples experience the joy of conceiving a child”

I called the bank the morning after I got my period (the day before Steve’s birthday) and made our first appointment.

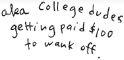

A week later, we were standing in front of a flat concrete-and-brick building, breathing through our coat collars, attempting to verify the building number on the other side of the people smoking. We crossed a dimly lit lobby and got onto a dimly lit elevator. There was still a chance the place would be gleaming and futuristic, on a secret, hermetically sealed floor, until the elevator doors opened. A man obscured another dimly lit floor.

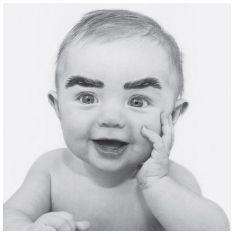

“Suzy, Stephen? Tom Mecke!” He threw out his hand and I shook it as I stepped off the elevator. There was something Oz-like about the welcome, a bushy-brown-eyebrowed director doubling as doorkeeper. Mecke led us down a short corridor by the lab, which was visible through the windows on our left. (The windows on our right were painted a mysterious milky blue, with a matching unmarked milky-blue door. He put on a white coat with a royal-blue cursive

Director

emblazoned on the left breast as we entered a small office. Mecke gestured to the now-empty coat tree. Steve and I hung up our coats and sat down. He opened the one folder, presumably ours, sitting on the empty desk, looked up at us, and launched into his welcome spiel. Every sentence seemed to contain the word “family.” It was holding up in all the different contexts—his family, our family, the family-run operation, part of the center’s family—and then it started to warp from overuse and the eyebrows dialed up a memory of that fertility doctor who fathered all the clients’ children.

“ . . . and now

you

must have some questions for me.” The eyebrows were on Steve. Steve looked at me.

My questions were so unfamilial. Bankerly. “Well, how often can Steve make a, a deposit?”

“We recommend waiting two days in between specimen collections.”

I got out my calendar. “Will we have enough after eight collections? We had been thinking twelve”—a year’s worth of tries—“since he lives in Australia.”

“It all depends how much Stephen produces, and the quality of the specimen.” The two men exchanged looks; Steve’s eyebrows were junior–bushy league. “We recommend at least two collections.” He looked through the folder. “Are we preparing these for intracervical or intrauterine insemination?” He paused. “Never mind, we’ve gotten ahead of ourselves here. Let’s have you meet with the doctor, Suzy, and we’ll have Stephen produce his specimen, then we’ll know exactly what we’re talking about.”

He handed me a folding chair and motioned toward the hallway as he led Steve off to the collection room. I unfolded the chair and set up with my back to the lab, angling for a glimpse into the milky-blue beyond. Ten minutes went by, nothing doing. Then a kindly-looking old man with wispy white hair came out of the office/collection area. I half stood to let him by, he half bowed in my direction, and we nearly banged heads. “I’m Dr. Felton. You’re Suzy?” I nodded. “I’ve just spoken with Stephen. I left him in there to—” his voice trailed off as he glanced up and down the hallway. “Well, this looks pretty private,” he said, unfolding himself a chair.

“Stephen and I went over all of his test results and his medical history. Has he shared any of this?” he held up the questionnaire. I nodded and he went on, “Then you’re aware Stephen”—

is gay. Yes, and I

—“had an undescended testicle?”

And now so is everyone in hearing distance.

Steve had actually mentioned it, under the heading of things he didn’t know until he had to fill out that questionnaire. “It was fixed,” I said, “operated on when he was one.”

My intimate knowledge impressed Dr. Felton enough for him to confide in me, “I have met some women who are

so

picky about their donors—I’ve been tempted to ask them, ‘Did you bother to ask your husband whether he was fertile before you married him?’” I smiled understandingly.

I

wasn’t one of those women.

Dr. Felton leafed though the rest of Steve’s packet, making passing reference to some heart and thyroid disease—all very common within an extended family. “I think we’re all set here,” he said when he got to the end. He smiled, rose, did another half bow in closing, then walked back to wherever it was he had come from. The heating system rumbled on in his wake—the HVAC opposite of the whir of a cryogenic cooling system—then rumbled off after he’d disappeared.

I kept my eyes fixed on the opening, willing Steve to reappear.

It didn’t take him this long at home!

I was studying the plaques above the doorway when Steve walked through, shaking his head. We refrained from further conversation until we were in the privacy of the elevator. “Well”—I couldn’t tell from looking at him—“how was it?”

“A blond Britney Spears type with a caveman—an unattractive caveman—”

“They only had

one

video?”

“No, it was the newest one. The doctor recommended it.”

“Wait, you don’t think he screens—”

“Mmm. It would seem he does. Well, I hope it went all right. It’s all very odd, really. I’ve never had to fuss about these things before . . . ” He zipped up his coat. “And how was your interview? ‘Stephen, you’ve had sex with men,’” he imitated Dr. Felton halfheartedly. “Does Suzy know?”

“Nope, nothing on that. He asked if I knew about your undescended testicle.”

“Good God.”

T

he lab didn’t have Steve’s sperm analysis the next morning. The receptionist picked up on my urgency. “Is your husband going in for chemo, Mrs. Dillon?” We

were

new to the agency family.

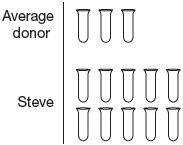

“Oh, no, he’s just going back to Australia. We’re trying to get his appointments set up.” She had no further questions. That afternoon she called back. “Ten dense vials with 96% motility fresh, 87% frozen,” I repeated aloud, although Steve had heard through the phone, and threw my arm around his waist.

S

TUDLY

S

TEVE

The receptionist scheduled appointments, one every three days through the end of December.

We called Lorene with the good news. “So are we celebrating?” she asked.

“Steve’s spending the night at Bruce’s. They’re going porn shopping. You and I were going to decorate the tree . . . ”

It was our first Christmas together but none of it was shaping up the way I had imagined. It was all my imagination’s fault: People in retail (Lorene, for example) don’t celebrate Christmas, they survive it. She had to work late, trying to keep up with the framing orders. And people from Australia (Steve, for instance) don’t care about making cookies or hanging stockings by a fireplace—it’s 95 degrees in Melbourne this time of year.