One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir (9 page)

Read One Good Egg: An Illustrated Memoir Online

Authors: Suzy Becker

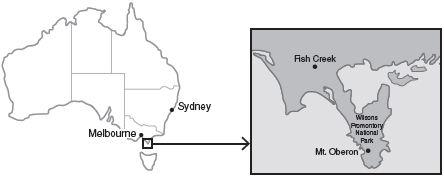

Our breakfast arrived. We were the only ones in the place. “Weather’s not so good. I thought maybe we’d go to Foster this afternoon, do a supermarket shop.”

“I need to do this tester thing before we go; I think I’m getting ready to ovulate.”

He laughed nervously. “Well, that makes things interesting. I suppose we could stay home and spend the afternoon in bed. Is that what you were thinking?”

“I’d be tomorrow or the next day, if it’s positive.” I paused. “I don’t know, when we used to talk about it, I always imagined the other two nearby. Feels like there should be some ground rules—”

“Shirts on, lights on. No, lights off!” We were laughing. “No, you’re right, it could be dangerous. What if we like it? How about we agree to do it just once . . . ” He shifted in his chair. “I’m sure you’ve thought about it. I’ve thought about it . . . ”

“I have. I—well, if we were both single . . . In this stupid, idealistic way, I always wanted this whole thing to be an act of love, not—not turkey baster or technology.”

I paid for breakfast and we left. “We don’t have to decide right now,” he said. “Do your test. We

could

call home.” The phone was in front of the post office, on the other side of our place.

“I don’t want to wake Lorene. I know what she’d say—‘Go for it!’”

“Same with Mark.”

We walked into the post office. Steve made a copy of his sperm-test results. I bought ten postcard stamps.

“As you wish, jellyfish,” the clerk said, and handed me the stamps in a little sleeve.

What

did

I wish? I wished for a baby. I wished Lorene was there. All of a sudden I had this strong feeling that I didn’t want her to miss the Moment.

When we got back, we each took a seat at the dining room table, our notebooks in front of us in place of place mats. “You go first,” Steve said. “I realized I don’t really have that many questions. I guess the trip itself was kind of a test balloon . . . I think I just needed to know how it would feel, to make sure, after all these years. Yeah. So I don’t have specific questions. I’m sure I will have them, after you go.”

“Okay, the first question. Have you given more thought to how much of a father you want to be?”

“Yeah. The distance is tough . . . My best friend Kelly sees his kids a few times a year. I was thinking once a year, at least. Maybe alternate, here, there, somewhere in between. What were you thinking?”

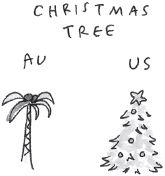

“Like that. With calls, letters, e-mail . . . Whatever we decide, I just want to make sure we can really do it. I don’t want to set the kid up for disappointment. And I want to celebrate birthdays and Christmas—”

“Together?”

“No, long distance. But they’d be important.”

“Definitely.” We stared at our notebooks. “Would you want me there for the birth?” he asked.

“Would you want me there for the birth?” he asked.

“Not a command performance. If you’d want to be there, I’d love it. I think. I have no idea what it’ll be like.”

“Who knows with any of this stuff? We should be allowed to change our minds . . . ”

“Except lowering the minimums on involvement.”

“Okay, here’s another one for you, then,” Steve said. “What if I fall in love at the birth, you know, with the baby, and decide I want to stay?”

“Fine. Just not in our house.”

“Next door?”

“Great. Here’s one for you. What if she hates us when she’s fourteen and she wants to come live with you?”

“Seriously?”

“I hope not.”

“That’d be just about perfect timing for me. I love high school kids.” Steve paused, then said, “My friends all think this is crazy. They keep saying—maybe it’s because of your brain surgery—‘Something’s going to happen to Suzy and Junior’s going to land on your doorstep.’”

“Lorene would get custody of Junior. Or do you mean if something happened to both of us? I was going to make my younger sister Meredith guardian in the will. You’d have visitation—would you want Junior?”

He thought for a bit. “I think you’re right . . . ”

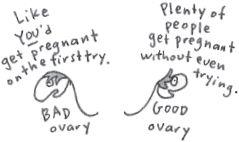

We talked through lunch and then I took my OPK into the bathroom. Steve raised his eyebrows when I came out. “It takes five minutes.”

Ovulation Predictor Kit (OPK)

The test detects the surge in luteinizing hormone (produced in the morning) which separates the egg from the follicle. Fertilization occurs 1 to 3 days later, 36 hours optimally.

We stood beholding the stick. Steve put his hand on my shoulder. “Darling, if we were going to be really responsible, I should have all my test results, right? The hep C results aren’t back yet.”

“That settles it?”

“I think so.”

“Could you possibly have hep C?”

“I don’t know. Let’s go to Foster.”

When I woke up the next morning, I reached for my purple thermometer. 97.1 degrees, the telltale drop.

If we were going to do it, this would be the day

.

The sun was out and so was our hot water, a conclusion I reached four minutes into a cold shower. I dried off, got dressed, and went down to the post office to buy a phone card. It was Bruce’s birthday.

“Nice place that, where you’re staying?” Mrs. Jellyfish inquired.

“It’s perfect for us, just no hot water this morning.” I offered up the intimate detail since this was our second meeting.

“It’s a chilly morning. Not as bad as yesterday. Tell your friend there to ring the owner up.” I was surprised she didn’t say “husband.”

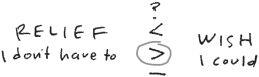

I left Bruce a singing message, then tried Lorene. Just a quick call to tell her I loved her, missed her, and we weren’t going to do it.

“Do you want to?”

“Kind of. If I got pregnant and we could skip the rest. ”

“You still could . . . ”

“I don’t want to bring it up again. Maybe when he’s there in the fall.”

She didn’t sound 10,000 miles away. “You okay?” I asked.

“I’m okay. The house is okay. Mister and Vita are okay. We miss you, but we’re fine. You okay?”

“I am. Feels selfish, though. I wish you were here.”

“It’s not selfish. It’s a wonderful thing you’re doing.”

Steve was padding down the walk in his house pants. “No hot water! I’m going to phone the guy.”

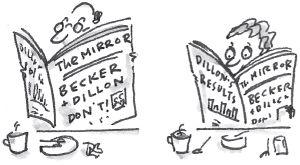

We adjusted our routine and headed to the Flying Cow. The owner looked up from her copy of the Fish Creek

Mirror.

“Heard your hot water heater’s stuffed. You’re welcome to shower in the back here.”

I turned to Steve. “Wait, how does she know?“

Steve shook his head and started laughing. “Small town, this.”

After breakfast we discussed finances and football. I would pay for all of the donation expenses and any of Steve’s testing that wasn’t covered under his insurance. He insisted on paying for his travel, including the sperm-banking trip. Aside from visiting, he wouldn’t have any further financial responsibility, which raised the topic of citizenship. Steve didn’t feel strongly, but if the baby were an Australian citizen, “uni”—university, our biggest foreseeable future outlay—would be free.

I segued to school in general. I felt strongly about sending the kid to public school. Steve wasn’t set on anything. He had been the equivalent of an American public high school teacher and graduated from the public schools, but he had seen friends’ kids benefit from private schooling.

“How much do you want to be a part of those kinds of decisions?”

“However much is useful. Parenting’s already tricky between two people, I don’t know that you want a third. But I’m happy to weigh in when you want. How’s that?”

“Good. What about football?” Lorene was opposed, I was pro—not pushing it, but if our kid wanted to play.

Steve didn’t know the first thing about American football, so he refused to cast the tie-breaking vote, saying instead, “Those things will usually sort themselves out.”