One minute to midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the brink of nuclear war (39 page)

Read One minute to midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the brink of nuclear war Online

Authors: Michael Dobbs

The commander of all 43,000 Soviet troops on Cuba, General Issa Pliyev (right), with Cuban defense minister Raul Castro (left). A former cavalry officer, Pliyev had little understanding of missile systems but was trusted by Khrushchev, who had ordered him to suppress food riots in southern Russia in June 1962.

[MAVI]

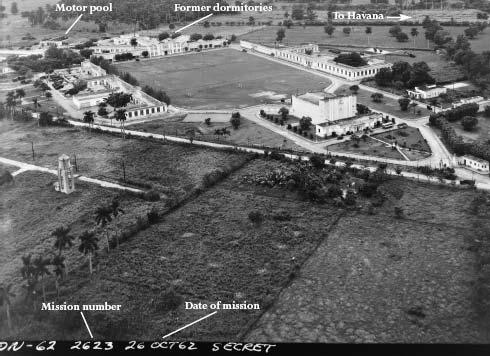

Previously unpublished U.S. reconnaissance photograph of Soviet military headquarters at El Chico, southwest of Havana, taken by Air Force RF-101s on Blue Moon Mission 2623 on October 26. The Americans knew the site by the nearby villages of Torrens and Lourdes. Prior to the revolution the campus had served as a boys' reform school.

[NARA]

Lt. Gerald Coffee (left) and Lt. Arthur Day (right) being debriefed by Rear Admiral Joseph M. Carson, commander of Fleet Air Jacksonville, immediately after returning from a mission over Cuba. Coffee and Day both came under Cuban antiaircraft fire on October 27. Coffee photographed nuclear capable FROG/Luna missiles on October 25.

[USNHC]

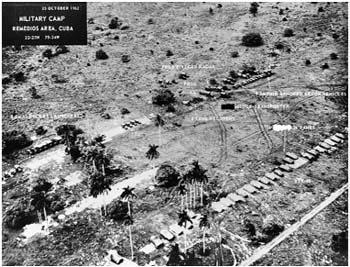

Photograph of nuclear capable FROG/Luna missiles near Remedios, taken by Lt. Coffee on Blue Moon Mission 5012 on October 25. As a result of this photograph, U.S. estimates of Soviet troops on Cuba rose sharply. President Kennedy was briefed about the photograph on the morning of October 26.

[NARA]

CHAPTER NINE

Hunt for the

Grozny

6:00 A.M. SATURDAY, OCTOBER 27

The news reaching the White House Situation Room was alarming. Five out of six medium-range missile sites in Cuba were "fully operational," according to the CIA. The sixth would "probably be fully operational" by Sunday. This meant that a large swathe of the southeastern United States was already within range of twenty 1-megaton nuclear warheads. Washington, and possibly New York, could be totally destroyed within ten minutes of the missiles lifting off from Cuba. In the event of a surprise Soviet attack, there would barely be time to evacuate the president from the White House.

Located in the basement of the West Wing, the Situation Room was a Kennedy innovation. JFK had been intensely frustrated by the lack of information available to him during the Bay of Pigs. Ham radio operators along the east coast heard about the disaster unfolding on the beach from intercepted radio transmissions hours before the commander in chief. He had to rely on unclassified telephone lines to find out what was going on at the CIA and the Pentagon. This must never happen again. He needed an information "nerve center" at the White House that would serve as "a war room for the Cold War."

The space used for the Situation Room had previously served as a bowling alley. The president's naval aide brought in Seabees to convert the area into a complex of four rooms that included a conference room, a file room, and a cramped watch center for the officers on duty. Communications circuits were installed in the West Wing, circumventing the need for hand-carried messages. There was a continuous clatter of teletypes outside the windowless conference room. The walls were covered with huge maps of Cuba and its sea approaches. Armed guards stood outside the door.

The maps apart, the conference room resembled a family den in a Washington suburb. It was decorated with functional Scandinavian-type furniture, including a flimsy-looking dining-room table and uncomfortable low-backed chairs, with recessed lighting and a couple of overhead spotlights. Kennedy described the warren of basement offices as "a pigpen." Nevertheless, the Situation Room fulfilled its purpose, providing him with a continuous stream of information that had traditionally been jealously guarded by semiautonomous government bureaucracies. The watch officers, who worked twenty-four-hour shifts followed by forty-eight hours off, all came from the CIA.

A wealth of information was flowing into the Situation Room by the time of the missile crisis. The president could listen to conversations between Navy Plot and the ships patrolling the quarantine line over single sideband radio. The White House received drop copies of the most important State Department and Pentagon telegrams. In addition to the news agency teletypes, there were also tickers for the Foreign Broadcast Information Service, which provided rush transcripts of Soviet government statements over Moscow Radio. Communications intercepts started arriving direct from the National Security Agency following complaints from Kennedy and McNamara about the delay in reporting the turnaround of Soviet ships.

Contrary to later myth, Kennedy refrained from issuing orders directly to the ships enforcing the blockade. Instead, he used the traditional chain of command, through the secretary of defense and chief of naval operations. Nevertheless, the fact that the White House could monitor military communications on a minute-by-minute basis had major implications for the Pentagon. The military chiefs feared that the very existence of the Situation Room would reduce their freedom of action--and they were correct. The relationship between the civilians and the military had undergone a profound change during the two decades since World War II. In the nuclear age, a political leader could no longer afford to trust his generals to make the right decision on their own, without close supervision.

From the Situation Room, duty officers kept track of the latest news from the blockade line. Plans were in place for a massive air attack against Cuba, followed by an invasion in approximately seven days. A tactical strike force of 576 warplanes, based at five different air bases, awaited the orders of the commander in chief. Five jet fighters were constantly in the air over Florida, ready to intercept Soviet war planes taking off from Cuba, while another 183 were on ground alert. Guantanamo was an armed garrison, guarded by 5,868 Marines. Another Marine division was on its way from the west coast, via the Panama Canal. More than 150,000 American troops had been mobilized for the ground invasion. The Navy had surrounded the island with three aircraft carriers, two heavy cruisers, and twenty-six destroyers, in addition to logistic support vessels.

But the Americans understood that the other side was ready as well. The CIA had reported that Cuban forces were being mobilized "at a rapid rate." All twenty-four Soviet SAM missile sites were now believed to be operational and therefore capable of shooting down high-flying U-2s. Low-level photography had provided the first concrete evidence of nuclear-capable FROG launchers on the island. Half a dozen Soviet cargo ships were still heading for the island--despite an assurance by Khrushchev to the United Nations that they would avoid the quarantine zone for the time being.

The Soviet ship closest to the barrier was called the

Grozny.

After permitting the

Vinnitsa

and the

Bucharest

to sail through the quarantine line, the ExComm wanted to show it had the resolve to stop and board a Soviet ship. The best candidate for interception appeared to be the 8,000-ton

Grozny.

She had a suspicious-looking deck cargo and had hesitated in the mid-Atlantic following the imposition of the blockade before eventually resuming her course. This "peculiar" behavior suggested that the Kremlin was unsure what to do with the ship.

Precisely what the

Grozny

was transporting in her large cylindrical deck tanks was hotly debated within the Kennedy administration. McNamara had told the president on Thursday that the tanks "probably" contained fuel for Soviet missiles on Cuba. In fact, the consensus at the CIA was that the vessel had nothing to do with the missile business and was instead delivering ammonia for a nickel plant in eastern Cuba. CIA experts had made a careful analysis of the nickel factory at Nicaro, which was one of several installations in Cuba targeted for sabotage under Operation Mongoose. They had kept a close watch on the

Grozny,

which had made several previous journeys to Cuba, unloading ammonia at Nicaro.

The ExComm was more interested in the public relations advantages of "grabbing" the

Grozny

than debating the contents of her deck tanks. The turnaround earlier in the week of obvious missile carriers like the

Kimovsk

had left a shortage of Soviet vessels to board. As Bobby Kennedy complained, only half in jest, "there are damned few trains on the Long Island Railroad." By Saturday, McNamara had changed his mind about the

Grozny,

telling the ExComm that he no longer believed she was transporting "prohibited material." But he thought the ship should be stopped anyway. To permit the

Grozny

to sail through to Cuba without an inspection would be a sign of American weakness.

The Air Force had managed to locate the

Grozny

on Thursday one thousand miles from the blockade line. But the Navy had been unable to keep track of the tanker, and had again asked the Air Force for help. Five RB-47 reconnaissance planes belonging to the Strategic Air Command had methodically combed the ocean on Friday, replacing each other at three-hour intervals. That search produced no results, and another five planes were assigned to mission "Baby Bonnet" on Saturday. They belonged to the 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing, whose motto was

"Videmus Omnia"

("We see everything").

Captain Joseph Carney took off from Kindley Field on Bermuda at dawn, and headed south toward the search area.

6:37 A.M. SATURDAY, OCTOBER 27

Three more reconnaissance planes were preparing to take off from Bermuda to join the search. The first RB-47 on the runway was piloted by Major William Britton, who had participated in the effort to locate the

Grozny

on Thursday. His crew included a copilot, a navigator, and an observer.

As Britton's plane moved down the short runway, heavy black smoke poured from its engines. The aircraft seemed to have trouble accelerating and did not become airborne until it reached a barrier at the end of the runway. Its left wing dropped sharply. Britton struggled to gain control of the aircraft, and succeeded in bringing his wings level. The plane cleared a low fence and a sparkling turquoise lagoon. On the opposite shore, the right wing dropped and grazed the side of a cliff. There was a loud explosion as the plane crashed to the ground, disintegrating on impact.

A subsequent investigation showed that the maintenancemen at Kindley had serviced the aircraft with the wrong kind of water-alcohol injection fluid. They were unfamiliar with the requirements of the reconnaissance planes, which normally flew out of Forbes Air Force Base in Kansas. The injection fluid was meant to give the engines extra thrust on takeoff, but the servicing actually reduced the thrust. The plane lacked sufficient power to get airborne.

Britton and his three crew members were all killed. The pilots of the other two planes aborted when they saw the fireball on the other side of the lagoon. As it turned out, the mission was unnecessary. Out in the Atlantic, six hundred miles to the south, Joseph Carney had just spotted a ship that looked like the

Grozny.

6:45 A.M. SATURDAY, OCTOBER 27

Carney had been assigned a search area measuring fifty by two hundred miles. The procedure was to locate a ship by radar, and then drop down for surveillance and recognition. The RB-47 dived in and out of the clouds as the navigator pointed out possible targets. Among the vessels spotted by Carney was an American destroyer, the USS

MacDonough,

which was also searching for the

Grozny.