One minute to midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the brink of nuclear war (18 page)

Read One minute to midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the brink of nuclear war Online

Authors: Michael Dobbs

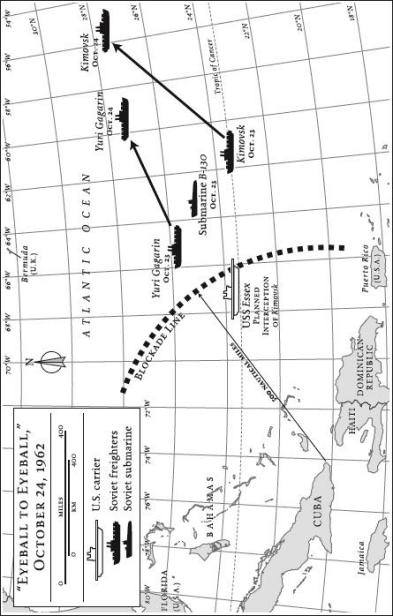

The mistaken notion that the Soviet ships turned around at the last moment in a tense battle of wills between Khrushchev and Kennedy has lingered for decades. The "eyeball to eyeball" imagery served the political interests of the Kennedy brothers, emphasizing their courage and coolness at a decisive moment in history. At first, even the CIA was confused. McCone erroneously believed that the

Kimovsk

"turned around when confronted by a Navy vessel" during an "attempted" intercept at 10:35 a.m. The news media played up the story of a narrowly averted confrontation on the quarantine line with Soviet ships "dead in the water." Later on, when intelligence analysts established what really happened, the White House failed to correct the historical record. Bobby Kennedy and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., would describe a standoff on "the edge of the quarantine line" with Soviet and American ships only "a few miles" apart. The myth was fed by popular books and movies like

Thirteen Days

and supposedly authoritative works like

Essence of Decision

and

One Hell of a Gamble.

Plotting the location of Soviet vessels was an inexact science at best, involving a considerable amount of guesswork. Occasionally, they were sighted by American warships or reconnaissance planes. But usually they were located by a World War II technique known as direction finding. When a ship sent a radio message, it was intercepted by U.S. Navy antennas in different parts of the world, from Maine to Florida to Scotland. The data was then transmitted to a control center near Andrews Air Force Base, south of Washington. By plotting the direction fixes on a map, and seeing where the lines intersected, analysts could locate the source of a radio signal with varying degrees of accuracy. Two fixes were acceptable, three or more ideal.

The

Kimovsk

had been located 300 miles east of the quarantine line at 3:00 a.m. Tuesday, eight hours after President Kennedy's television broadcast announcing the blockade. By 10:00 a.m. Wednesday--just over thirty hours later--she was a further 450 miles to the east, clearly on her way home. An intercepted radio message indicated that the ship--whose cargo holds contained half a dozen R-14 missiles--was "en route to the Baltic sea."

The fixes on other Soviet ships trickled in gradually, so there was no precise "Eureka moment" when the intelligence community determined that Khrushchev had blinked. The naval staff suspected that Soviet vessels were transmitting false radio messages to conceal their true movements. American calculations of Soviet ship positions were sometimes wildly inaccurate because of a false message or a mistaken assumption. Even if the underlying information was correct, direction fixes could be off by up to ninety miles.

Intelligence analysts from different agencies had argued all night over how to interpret the data. It was not until they received multiple confirmations of the turnaround that they felt confident enough to inform the White House. They eventually concluded that at least half a dozen "high-interest" ships had turned back by noon on Tuesday.

ExComm members were disturbed by the lack of real-time information. McNamara, in particular, felt that the Navy should have shared its data hours earlier, even though some of it was ambiguous. He had visited Flag Plot before going to the White House for the ExComm meeting, but intelligence officers had termed the early reports of course changes "inconclusive" and had not bothered to inform him.

As it turned out, the Navy brass knew little more than the White House. Communications circuits were overloaded and there was a four-hour delay in "emergency" message traffic. The next category down, "operational-immediate traffic," was backed up five to seven hours. While the Navy had fairly good information about what was happening in Cuban waters, sightings of Soviet ships in the mid-Atlantic were relatively rare. "I'm amazed we don't get any more from air reconnaissance," Admiral Anderson grumbled to an aide.

Electronic intelligence was under the control of the National Security Agency (NSA), the secretive code-breaking department in Fort Meade, Maryland, whose initials were sometimes jokingly interpreted to mean "No Such Agency." That afternoon, NSA received urgent instructions to pipe its data directly into the White House Situation Room. The politicians were determined not to be left in the dark again.

When intelligence analysts finally sorted through the data, it became apparent that the

Kimovsk

and other missile-carrying ships had all turned around on Tuesday morning, leaving just a few civilian tankers and freighters to continue toward Cuba. The records of the nonconfrontation are now at the National Archives and the John F. Kennedy Library. The myth of the "eyeball to eyeball" moment persisted because previous historians of the missile crisis failed to use these records to plot the actual positions of Soviet ships on the morning of Wednesday, October 24.

The truth is that Khrushchev had "blinked" on the first night of the crisis--but it took nearly thirty hours for the "blink" to become visible to decision makers in Washington. The real danger came not from the missile-carrying ships, which were all headed back to the Soviet Union by now, but from the four Foxtrot-class submarines still lurking in the western Atlantic.

11:04 A.M. WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 24

The Foxtrot-class submarine that caused JFK to cover his mouth with his hand and stare bleakly at his brother bore the Soviet designation

B-130.

On Tuesday morning, the submarine had been keeping a protective eye on the

Kimovsk

and the

Yuri Gagarin

in the Sargasso Sea. After the two arms-carrying ships turned back toward Europe on orders from Moscow,

B-130

was left alone in the middle of the ocean.

The U.S. Navy had been monitoring

B-130

and the three other Foxtrots ever since they slipped out of the Soviet submarine base at Gadzhievo on the northern tip of the Kola Peninsula on the night of October 1. Electronic eavesdroppers followed the flotilla as it rounded the coast of Norway and moved down into the Atlantic, between Iceland and the western coast of Scotland. Whenever one of the Foxtrots communicated with Moscow--which it was required to do at least once a day--it risked giving away its general location. The bursts of data, sometimes lasting just a few seconds, were intercepted by listening posts scattered across the Atlantic, from Scotland to New England. By getting multiple fixes on the source of the signal, the submarine hunters could get a rough idea of the whereabouts of their prey.

As the missile crisis heated up, the intelligence community launched an all-out effort to locate Soviet submarines. On Monday, October 22--the day of Kennedy's speech to the nation--McCone reported to the president that several Soviet Foxtrots were "in a position to reach Cuba in about a week." Admiral Anderson warned his fleet commanders of the possibility of "surprise attacks by Soviet submarines," and urged them to "use all available intelligence, deceptive tactics, and evasion." He signed the message: "Good Luck, George."

The discovery of Soviet submarines off the eastern coast of the United States shocked the American military establishment. The superpower competition had taken a new turn. Until now, the United States had enjoyed almost total underwater superiority over the Soviet Union. American nuclear-powered Polaris submarines based in Scotland were able to patrol the borders of the Soviet Union at will. The Soviet submarine fleet was largely confined to the Arctic Ocean, posing no significant threat to the continental United States.

There had been rumors that the Soviets were planning to construct a submarine base at the Cuban port of Mariel under the guise of a fishing port. But Khrushchev had personally denied the allegation in a conversation with the U.S. ambassador to Moscow. "I give you my word," he had told Foy Kohler on October 16, as the four Foxtrots headed westward across the Atlantic on precisely this mission. The fishing port was just a fishing port, Khrushchev insisted.

The commander of allied forces in the Atlantic, Admiral Robert L. Dennison, was alarmed by the appearance of Soviet submarines in his area of operations. He believed their deployment was equal in significance to "the appearance of the ballistic missiles in Cuba because it demonstrates a clear cut Soviet intent to position a major offensive threat off our shores." This was "the first time Soviet submarines have ever been positively identified off our East Coast." It was obvious that the decision to deploy the submarines must have been taken many weeks previously, long before the imposition of the U.S. naval blockade.

Patrol planes were dispatched from Bermuda and Puerto Rico on Wednesday morning to find the submarine close to the last reported positions of the

Kimovsk

and the

Yuri Gagarin.

A P5M Marlin from Bermuda Naval Air Station was first on the scene. At 11:04 a.m. Washington time, a spotter onboard the eight-seat seaplane caught a glimpse of the telltale swirl produced by a snorkel five hundred miles south of Bermuda. "Initial class probable sub," the commander of the antisubmarine force reported to Anderson. "Not U.S. or known friendly." A flotilla of American warships, planes, and helicopters led by the

Essex

was soon converging on the area.

What had started off as an exotic adventure for the commander of

B-130,

Captain Nikolai Shumkov, had turned into a nightmarish journey. One thing after another had gone wrong, starting with the batteries. To outwit American submarine hunters,

B-130

needed to glide silently through the ocean. The noise from the diesel engines of a Foxtrot submarine was easy to detect. The submarine was much quieter while running on batteries, but its speed was also reduced. Shumkov had asked for new batteries before his deployment, but his request was rejected. After a few days at sea, he realized that the batteries would not hold a charge for as long as they should, forcing him to surface frequently in order to recharge them.

The next problem was with the weather, which got steadily warmer as the submarines moved from the Arctic Ocean to the Atlantic Ocean to the Sargasso Sea. Halfway across the Atlantic, Shumkov had run into Hurricane Ella and winds of more than one hundred miles an hour. Most of his seventy-eight-man crew fell seasick. As

B-130

reached tropical waters, the temperature inside the submarine rose as high as 140 degrees, with 90 percent humidity. The men suffered from severe dehydration, exacerbated by a shortage of fresh water. The heat, the turbulence, and the noxious stench of diesel and fuel oil combined to make conditions aboard ship almost unbearable.

The commanders back home wanted him to maintain an average speed of at least 9 knots, in order to reach Cuba by the end of the month. Since the underwater speed of a Foxtrot was only 6 to 8 knots, Shumkov was forced to run his diesels at maximum speed while on the surface. By the time

B-130

reached the Sargasso Sea, an elongated body of water stretching into the Atlantic from Bermuda, two of its three diesels had stopped working. The monster submarine--

B

stood for "Bolshoi," or "Big"--was barely limping along.

Shumkov knew the Americans were closing in on him; he had intercepted their communications. A signals intelligence team had been assigned to each of the Foxtrot submarines. By tuning in to U.S. Navy frequencies in Bermuda and Puerto Rico, the Soviet submariners had found out that they were being tracked by American antisubmarine warfare units. Shumkov learned about the deployment of Soviet nuclear weapons to Cuba, the imposition of a naval blockade, and preparations for a U.S. invasion from American radio stations. One broadcast even mentioned that "special camps are being prepared on the Florida peninsula for Russian prisoners of war."

Shumkov comforted himself with the thought that the Americans had not discovered the most important secret of his submarine. Stacked in the bow of the

B-130

was a 10-kiloton nuclear torpedo. Shumkov understood the power of the weapon better than anyone in the Soviet navy because he had been selected to conduct the first live test of the T-5 torpedo in the Arctic Ocean on October 23,1961, almost exactly a year earlier. He had observed the blinding flash of the detonation through his periscope, and had felt the shock waves from the blast five miles away. The exploit had won him the Order of Lenin, the Soviet Union's highest award.

Before their departure, the submarine commanders had been given an enigmatic instruction by the deputy head of the Soviet navy, Admiral Vitaly Fokin, on how to respond to an American attack. "If they slap you on the left cheek, do not let them slap you on the right one."

Shumkov knew that he could blast the fleet of U.S. warships converging down upon him out of the water with the push of a button. He controlled a weapon that had more than half the destructive force of a Hiroshima-type nuclear bomb.

11:10 A.M. WEDNESDAY (10:10 A.M. OMAHA)

While the hunt continued for Soviet submarine

B-130,

the commander in chief of the Strategic Air Command was preparing to signal the Kremlin that the most powerful military force in history was ready to go to war. From his underground command post at SAC headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska, General Thomas Power could instantly see the disposition of his forces around the world. The information on the overhead screens was constantly updated to show the number of warplanes and missiles on alert.